Why We Grieve Differently for Actors

A sense of personal loss

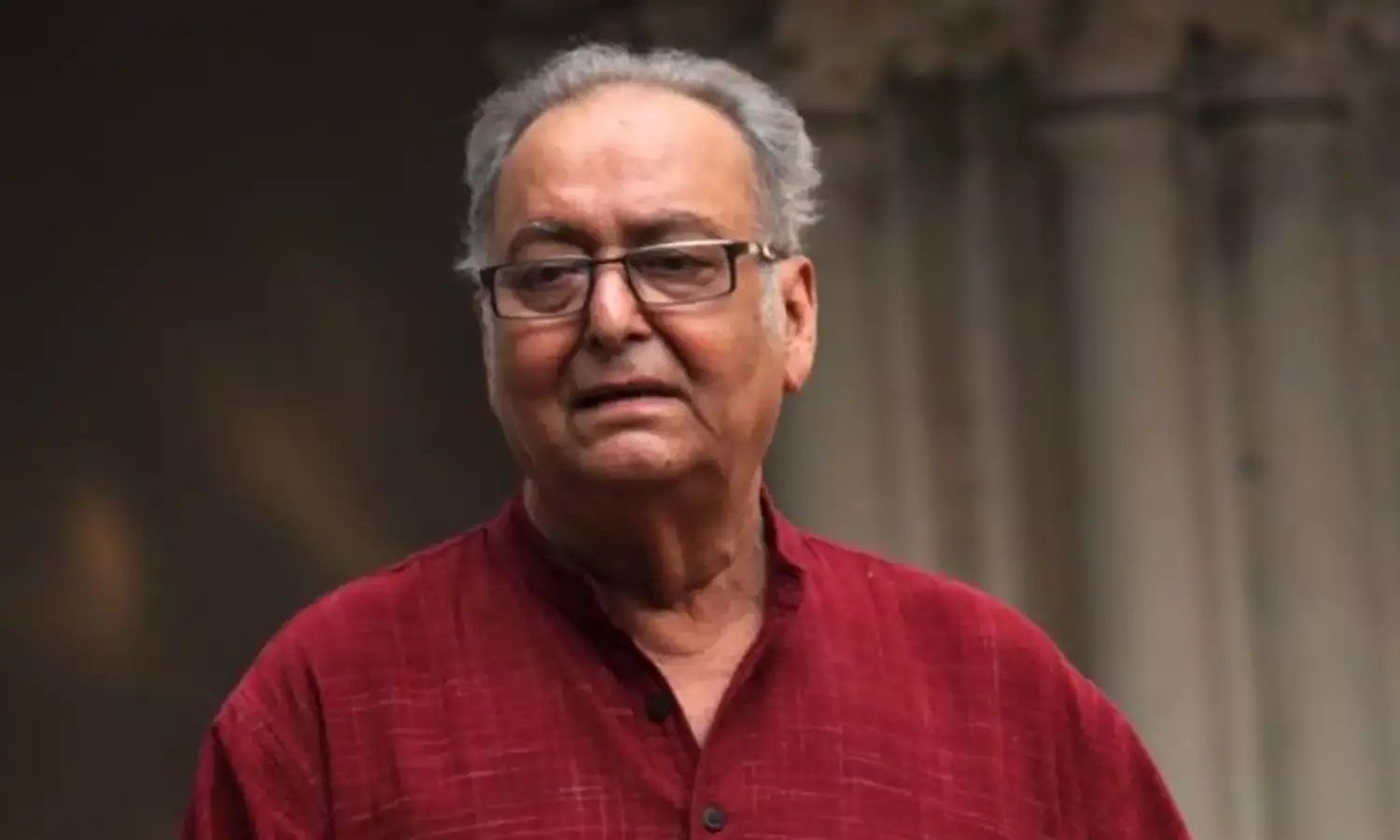

Legendary actor Soumitra Chatterjee, best known for his work with stalwart director Satyajit Ray, passed away recently. Fans accumulated over a six decade long career in Bengali-language cinema mourned. They mourned an accomplished performer, a cultural icon, an engaged citizen, a fine human being.

Above all, however, fans mourned the bits of themselves that had twined with Chatterjee, the spaces within themselves they had welcomed him into. Gone was the man who populated some of their most abiding memories and inspired how they dressed, wooed, conversed. He was gone, vacating the niches he occupied in their lives, never to return, and it hurt. Sure, they were phantom niches, but then that is how the public figure is supposed to be, remote but around.

A similar sense of personal loss followed the passing of Irrfan Khan and Rishi Kapoor, two other celebrated actors India lost earlier this year. Even the relatively humble-statured Sushant Singh Rajput’s death by suicide sparked spontaneous emotional outpourings before the tragedy got spun into an ugly news opera.

A politician’s loss is less intensely felt at the individual level. (This is not to be confused with the grand collective send-off. Those can be, and typically are, orchestrated.) It owes to the nature of political practice, modern political practice at any rate, where leaders align themselves with specific parties and ideologies, flatter and demonize different population groups with equal seriousness, make sweeping, far-reaching choices from morally denuded, self-serving menus. Making enemies is unavoidable here, they know; the idea is to win a slightly larger number of friends.

It all makes for a complicated politician-citizen relationship, marked by the anger and indifference of the ignored and the betrayed and the manipulated, transactional affections of the patronized. When the politicians exits this messy arena, there is sadness, but it is often the sadness that decency demands, nothing particularly genuine.

As the range and texture of reactions to the recent passing of politicians Pranab Mukherjee and Ram Vilas Paswan showed, the expected surge of post-mortem goodwill is adulterated, laced with recalls of deeds unpardoned and the noise of keen legacy claimants. Even the goodwill on display resounds as much with the burp of sated interests as it does with the lament of grateful commoners.

Quite simply, partisan and insincere choices make for partisan and insincere grievings. It takes the extraordinary moral force of a Mahatma Gandhi, the rare vision and charisma of a Jawaharlal Nehru, or the courage and sacrifice of other tall Independence movement leaders – also, a less skeptical, less torn era - to earn the heartfelt farewell.

The star sportspersons’ relationship with the people is more like the actor’s than the politician’s. Like the actor, he - in the Indian context, an eminent sportsperson is most likely a male cricketer – creates, inhabits, and completes special moments in his audience’s lives. And, unlike the politician, he is non-divisive and harmless (in the broader scheme of things) and relies more on performance than rhetoric to earn his spurs.

Yet, a sportsperson’s passing could move us differently, dare one say, less deeply, than the actor’s. The sportsperson can be many things – world beater, role model, ace stylist – but relates to the world primarily as a player. The adulation he commands is as a player alone, and the people who laud him, except the few determined to make a career in sports, have no realistic aspirations to the sporting heights he has attained.

Contrast this with the actor. The actor is all those things we are, lover, friend, parent, sibling, daughter/ son, colleague, and that too in the charming, dutiful, brave version of these that we want to be. Or s/he is all those people we secretly fantasize about becoming, the seething do-gooder, the shrewd professional, even the intense, wealth and power-obsessed antagonist. So, somewhat counter-intuitively, we connect more with actor-characters in unreal, even fantastic situations than sporting heroes in real ones.

Yes, this means that great actors wouldn’t be where they reach without the characters writers fashion and directors and technicians realize for them. That said, rounding up the best crew is no guarantee of high stardom. The tallest actors inject something special into characters they play: slices of their own unique selves, of the winsome allure and inflexions that lesser actors simply don’t have and can’t cultivate, of the personal vulnerabilities that connects audiences. It is with these peeks at themselves, these surrenders of self, that actors seep into us. When they go, no wonder it feels wrung.