EU Border Security and Arms Exports Create Circle of Profit

‘Sanction member states that make problematic arms exports’

The EU is militarising its borders. A €7 billion Internal Security Fund has been used since 2014 for border surveillance and security, coast guard patrols, and information exchange with non-government “third parties” to violently regulate the journey of refugees into Europe.

In January 2021 the Fund was used to raise a standing corps of 10,000 personnel for the European Border and Coast Guard. These include personnel from the coast guard agency Frontex, which has repeatedly been accused of violating international law.

“The expansion of Frontex has continued unabated, despite repeated allegations of misconduct, questionably aiding and abetting actors, and violating International Human Rights Law and International Maritime Law in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean,” write the authors of a new report.

Authored by the research and advocacy Transnational Institute, Smoking Guns: How European arms exports are forcing millions from their homes shows how EU states have evolved a securitised approach to “migration management” away from public scrutiny.

The report documents how this militarisation proceeded “alongside the steady increase in the value of the arms trade, and the spiralling number of forcibly displaced persons” attacked using European weapons.

As these displaced civilians seek refuge, “the market for border security is growing and is expected to be worth US$65–68 billion by 2025.”

Besides the Internal Security Fund, “migration management” itself is being exported to Africa, largely to countries on the northern frontier.

A €5 billion Trust Fund for Africa running since 2015 has used a third of its corpus on public-private projects for migration management, with contracts amounting to €700 million in northern Africa alone.

Largely funded by EU members, the Trust Fund has built border stations and border control facilities, early-warning systems for migration flows, and facilities to “return” migrants to 27 African countries.

It has also paid for the training of over 42,000 “staff from governmental institutions, internal security forces and relevant non-state actors” in “security, border management, [countering violent extremism], conflict prevention, protection of civilian populations and human rights.”

The remainder of the Trust Fund is claimed for “income-generating activities”, basic services such as nutrition and water, “improving governance” and events to raise awareness about migration among the African public.

Contracts for these services worth €3.5 billion are given to various European national development agencies, to NGOs including CARE and Save the Children, and agencies of the United Nations.

While promoters of the Trust Fund for Africa say it will help address the “root causes” of migration into Europe, the Smoking Guns report documents the missing root cause: violence exported by EU governments and the arms businesses they host.

While EU states adopt a collective approach to asylum, immigration, border security and defence, they have ensured that weapons trade and export policies remain strictly national, with little oversight or accountability.

“Between 2015 and 2020, under the leadership of former president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Junker, the EU took unprecedented steps in expanding its defence policy,” the report observes.

The expansion includes a multi-billion euro European Defence Fund, to “promote defence cooperation among companies and between EU countries” to develop state of the art defence technologies.

It also includes a €5 billion European Peace Facility, meant to “fund the common costs” of EU military operations.

Calling for the abolition of the Peace Facility, the report’s authors describe it as “an off-budget fund, crafted specifically for the purpose of circumventing EU regulations on financing military activity and engagement.”

Similar to India’s unprecedented arms exports to Myanmar during the genocide of Rohingyas, they document the circularity of profits in this trade. First by exporting weapons that violently displace civilians, then by spending on defence and border security to keep them out.

“Deeply embedded in the massive profits being made by the border security industry is the arms licensing and export industry,” the report observes.

The Citizen spoke with Smoking Guns co-author Niamh Ni Bhrian, coordinator of the war and pacification programme at the Transnational Institute.

You mention some success in arms control through public pressure and litigation in Italy and Germany. Are certain EU governments or states more assertive, responsive to these concerns than others?

My reading of both Germany and Italy, but also of others, is that they are more keen to continue arms trade deals than willingly engage with a process that would involve a political shift.

In the case of Germany for example, taking the case brought by ECCHR and others, the arms company (Heckler and Koch) and the state aligned in appealing the verdict handed down by the court, which is an indicator of where their interests and their loyalties lie.

Similarly in Italy, they continue to approve licences. Other states are doing the same thing. I didn’t come across any example where I genuinely thought that a state was willing to engage in a more constructive approach to arms trade and regulations.

Governments are always defensive on the issue of arms exports, also in reaction to public and parliamentary criticism.

In general there are (sometimes vast) differences in the ways EU member states implement the EU Common Position, which leads to very different arms export policies.

The Netherlands, Germany and Sweden are often more restrictive (though there are cases of very problematic arms exports for each of them) while France and Middle European countries like Bulgaria and the Czech Republic are known for their lax attitude.

Are there recent instances of a revolving door between EU governments and arms manufacturers?

I am not familiar on an individual member state level but at an EU level there are Thierry Breton, going from CEO of Atos to Commissioner for Defence Industry, and Jorge Domecq, going from Chief Executive of the European Defence Agency to Strategic Advisor at Airbus.

[Thierry Breton was nominated by French president Emmanuel Macron as internal market commissioner in December 2019, with powers to regulate the defence and space technology business. Until that time he headed Atos, an $8 billion IT company with interests in the aerospace and defence industry.

[After Jorge Domecq’s migration to Airbus, the European Ombudsman ruled in July 2021 that the European Defence Agency regulator should change its rules to prevent such conflicts of interest in future.]

Would you hazard an estimate of (a) what fraction of EU arms are exported through private contractors (b) are exported directly to non-government actors, including militias and security contractors?

My sense is that the deal would always go through a government actor, at least this was the case in all of the case studies that we covered, but also because we specifically chose to focus on states.

In terms of arms licences, as I understood it, they would be through governments. There are seldom (legal) arms exports to private actors, outside demilitarised things (vehicles for example) or components that go from one company to the other for inclusion in larger arms.

Of course there are many cases of arms being exported legally and then being diverted, as the Conflict Armaments Research report highlights and as we picked up in our report.

There have been some exports to non-state actors in conflicts (ie Kurds in Syria and Iraq) but then the supplier was a state in the context of political decision-making.

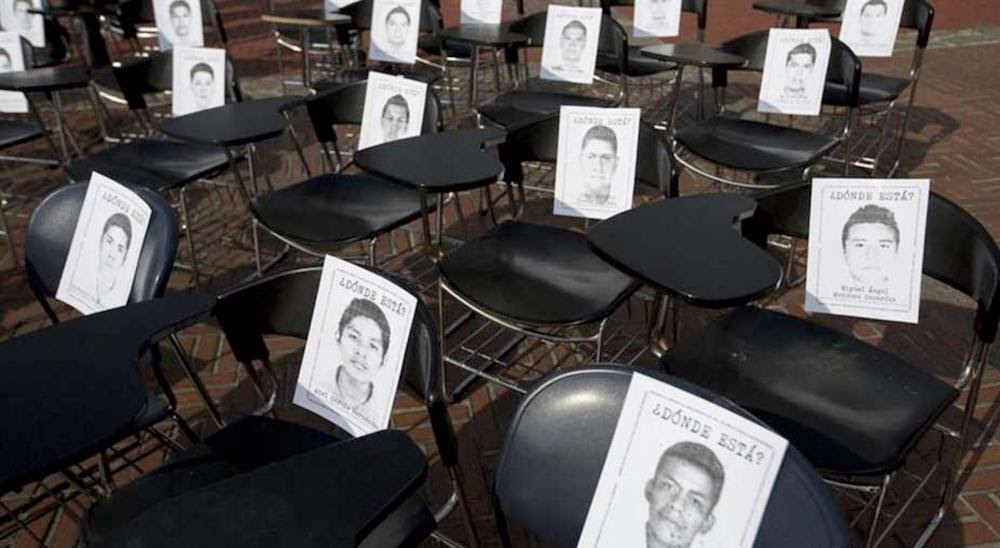

Like the ‘unauthorised’ exports of H&K rifles from Germany, used by Mexican police against college students, what is your sense of the proportion of EU arms exported off the books, so to speak, below the public radar?

I think the thing with the German rifles ending up in México – this wasn’t entirely unauthorised, quite the opposite. It was very much authorised, at least to México. But then it gets murky because the arms were moved from Federal to State officials, although the distinction is pretty useless to be honest because the federal forces are just as problematic as state forces in many ways.

As regards ‘off the books’ I don’t know about the proportions, but I think when we focus on off the book deals we move in to making a different political argument. It kind of loses the point if we focus on off the books: the aspects of the report we focused on were all on the books, reported on, and caused huge destruction and devastation.

The question is basically about illegal arms trade and that is really quite a different question. Illegal exports, unless the state knowingly lets them happen or otherwise facilitates them, is more about the criminal circuit. [Firearms are] the main problem here: it is of course harder to illegally export helicopters or vessels than small arms and light weapons.

What happens more often is that exporters don’t know where arms actually end up (diversion or direct or later resales) and that there is hardly any control on end users.

It is a huge problem that arms keep going from one conflict to the other, as we saw for example very clearly after the end of the wars in former Yugoslavia (many of the small arms used ended up in conflicts in Africa) and with Libya.

The European Parliament said in 2018 that it was “shocked at the amount of EU-made weapons and ammunition found in the hands of Da’esh in Syria and Iraq” and called for closer scrutiny.

The following year the Transnational Institute sent queries to weapons-exporting governments about the diversion of arms they were selling, and whether they implement post-shipment inspections or controls.

Austria (which earned $2.7 billion from arms exports and licences in 2017) said it would “undertake for the first time an onsite post-shipment control after the current health crises” allowed it.

France ($15.2 billion) ignored the queries, as did Bulgaria ($2.9 billion), Sweden ($2.2 billion), Belgium ($831 million), Croatia ($588 million), Romania ($513 million) and the UK ($20 billion), which replied with a link.

Norway’s foreign ministry ($648 million) said it did not implement any post-shipment controls, while Spain’s commerce ministry ($28.5 billion) said a law making inspections “possible“ was only passed in April last year.

Italy ($14 billion) said its post-shipment controls did not include inspections, while export controls included “assessing the extent of domestic diversion in the recipient Country, verifying the accuracy of information provided by the Italian exporting company, specific controls on the declared end user”.

Italy’s former interior minister Marco Minniti now heads the Med-Or Foundation, funded by one of Europe’s biggest arms manufacturers, Leonardo S.p.A.

The report recommends the involvement of outside experts in conducting post-shipment reviews and broader measures for arms control. It also calls for an accountability mechanism involving outside experts “mandated to follow up and sanction EU member states that make problematic arms exports.”

Germany ($10.2 billion in 2017) described an export control policy implemented since its export of rifles to Mexico that were used in 2016 to murder and “disappear” over 40 college students.

The policy introduces a clause in arms export licences to let German authorities “perform on site inspection whenever we want“.

The German government added that the challenges to enforcing this are substantial: “It is not like we can show up and knock on the door and expect to be invited in to do the controls we want.”

The clause has been included in deals with ten customer countries, including the UAE and India. NATO members and affiliates are exempt from the inspections clause.