‘Apna Pukka Ghar Banayenge Amma…”

Homebound says it all

It could have been a page out of the backwaters of north India. Madhya Pradesh as it was said to be, or Uttar Pradesh as it actually was. Stories and reality that reporters have witnessed and documented over the years and decades, but never expected to be seen in a movie hall with the nuances and the settings as real as real life. From the aspirations and hope of youth to chilling reality, death and resignation. Tragedy lives on a daily basis, a struggle that never ends, dreams that disappear, as discrimination and poverty take over life that often does not seem worth the living.

But it is also a story of compassion and humanity. And deep sensitivity. It took a sensitive, compassionate journalist to go behind a photograph, a ‘grainy photograph’ that came his way in 2020 when the Corona virus was sweeping the world, and India had declared a sudden lockdown. The photograph was of two young men, sitting on an empty highway bridge, with their little bundles of belongings strewn around them as one cradled the other in a desperate attempt to revive him even though he was dead.

Basharat Peer was so moved by the photograph that he resolved to trace the boys, their families, their lives. He found their families in Basti, Uttar Pradesh. And the article that was carried in the New York Times is now in movie theatres under the title Homebound. India’s entry for the Oscars, even though the Censor Board dove deep into the movie with a hard whip. Even so it was not able to take away from one of the best movies made in recent years, and as a movie buff said, “it is Do Bigha Zameen of our times.”

Under Director Neeraj Ghaywan and mentor and godfather Martin Scorsese, Homebound is reality, stark, extremely depressing and yet extremely courageous and beautiful in its approach. Every scene is a commentary on the system with innocence and hope turning into deep despair. Sentiments that the audience shares. Every scene is framed, set and shot with a precision set into motion by the director and beautifully portrayed by the actors.

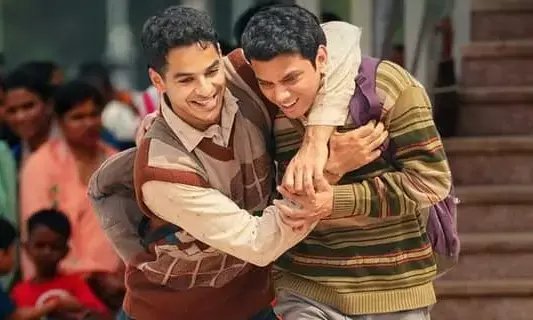

Homebound is what we have grown up with, and covered as journalists.The protagonists are two young boys from a small village - a Muslim and a Dalit. Close friends who have grown up together in families that love them and each other, with respect and dignity underlying the relationships. Ishaan Khattar as Mohammad Shoaib Ali, and Vishal Jethwa as Chandan Kumar get right into your hearts and psyche, their journey yours as you weep with them, laugh when they laugh, feel their hurt, their despair, their loss, their helplessness.

A police recruitment examination establishes so much. Railway platforms crowded with aspirants who cannot get a place to stand let alone sit; delayed trains; last minute platform changes that almost lead to stampedes; the suffocating train journey that leaves the aspirants exhausted. A war to just travel that extends to cover most aspects of their lives. And yet at this moment it is laced with hope, a belief that they will somehow beat the odds - over 700 candidates for one police constable post–and change their and their families destiny. Dreams. Realistic dreams of having a proper house with a roof that does not leak, of buying slippers and shoes for the parents and siblings, nothing big, all small and yet feeding into hope for a better future.

Both friends try to beat the system (for want of another word here) that has boxed India’s poor into walls made of caste and religion. Chandan tries to beat it by not claiming the Scheduled Caste status and ticking the ‘General’ category box. He wants to win on merit. Shoaib does it by refusing a relative's offer to work in Dubai, insisting he cannot leave his home and his family and his country. There is this belief that they can move out of the box, and lead a better life. They sit for the exams but the results are postponed over and over again. There are no jobs, no money. Anyways, finally Chandan gets the recruitment notice, Shoiab does not. The disappointment makes the friends fall out.

There is this personal story. In a system that is brutal. Shoaib realises that he is not equal. That there is discrimination based on religion. Barbs and taunts that are completely twisted. He first realises it when they are playing cricket in their more innocent days, and he faces the slur of religion. This is further reinforced when he gets a job as a peon to earn some money to survive, and is watching a India Pakistan cricket match, cheering loudly for his Indian team. India loses, and one of his employers taunts him for supporting Pakistan!. It is so real to life, and such a lie, and the emotions that Khattar shares on the screen mirrors the anger and disappointment and shock and tears of reality.

Chandan faces it when his mother who cooks the midday meals at a school is kicked out because she is a Dalit. Parents of the upper caste students who by the way love her cooking, storm the school and insist that their children cannot eat the food cooked by her. The family watches helplessly, and Shalini Vatsa who plays Chandan’s mother, is absolutely brilliant throughout the movie. A proud hardworking Dalit woman, who has pinned all her hopes on her son, to the point where her daughter feels the discrimination and says so in a conversation with her brother. She also had dreams but was forced to suppress these —-as young girls I have personally met in Siddharthanagar in eastern Uttar Pradesh said they had no choice but to stay at home—so that the meagre resources of the family could sustain Chandan to get a government police job.

Homebound marks the struggles of two families, of friends, of hope but more of desperation, of discrimination, of migrants who seek jobs outside their villages and their districts and states when all else fails them. It provides a much needed look into the background of the workers who we take for granted, but who have come from families who love them, pushed by poverty to eke a living, any living, while their mothers wait for them to return. The impact of Covid, the fear spread by the sudden lockdown, the police action took a toll and scared witless the migrants decided to leave for their villages. Such is the fear that they decide to walk the 1000 km rather than stay in the hovels, away from family, without food, and without a job. So also Shoaib and Chandan who take the long walk home, with the film capturing the sheer isolation of the poor who are left to fend for themselves. The only establishment visible is the lathi of the police, nothing else. No food, no transport, no water, nothing. As if government and governance ceased to exist.

Neeraj Ghaywan has excelled, as have the actors. One could hear muffled sobbing in the auditorium, although I must confess I did not shed a tear. Not because it was not moving, but perhaps because it was too moving. And too close to a reality one has seen in the villages and districts of India. I have met so many Chandans and Shoaib’s in this world, and perhaps they had exhausted my tears. Or perhaps life has taught hacks like me that tears mean little, and are a luxury for those impacted by poverty and a cruel indifferent system. As dreams of the young shatter when they realise that justice and equality are not for them. I kept hoping that the movie would end like Bollywood films and bring in a fairy tale ending. And would leave us with hope even though I knew that that could not be.

The nine minute standing ovation for Homebound at Cannes perhaps then is the hope. As is the fact that it is our entry for the Oscars. Recognition can lead to solutions.