CEC Fails to Reassure

A Press Conference that did not dispel doubts

Of late, the Election Commission (EC) of India has been under tremendous pressure. One reason is the Supreme Court’s ongoing hearing on several petitions concerning the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls in Bihar. The larger headache, however, comes from the Opposition’s relentless charge—led by Rahul Gandhi—that voters’ lists across states have been manipulated on a massive scale to tilt the process in favour of the ruling BJP.

Rahul Gandhi’s allegations, citing serious defects in the rolls of states such as Karnataka and Maharashtra, have cast doubt on the integrity of electoral lists nationwide. Combined with the SIR in Bihar—where polls must be held before 22 November 2025—these charges have shaken public confidence in the Commission.

In court, the EC resisted publishing the list of 65 lakh voters deleted from the rolls and opposed the acceptance of Aadhaar cards as valid documents for SIR. The Supreme Court overruled the Commission, directing it to publish the names of those deleted along with reasons, and to accept Aadhaar as one of the supporting documents.

When Rahul Gandhi went public with documents he claimed were drawn from the EC’s data, the Commission did not launch a probe. Instead, through state Chief Electoral Officers, it served notices on him demanding that he either submit evidence with an affidavit or apologise for “misleading” the public.

The BJP, meanwhile, rushed to counter Rahul Gandhi’s claims, raising questions about whether the party was defending the EC—or the other way around. Union Minister Anurag Thakur alleged that the Diamond Harbour rolls were riddled with duplications and ineligible voters. Since the Commission prepares the rolls, his charge was effectively against it. Yet, no notice was served on Thakur.

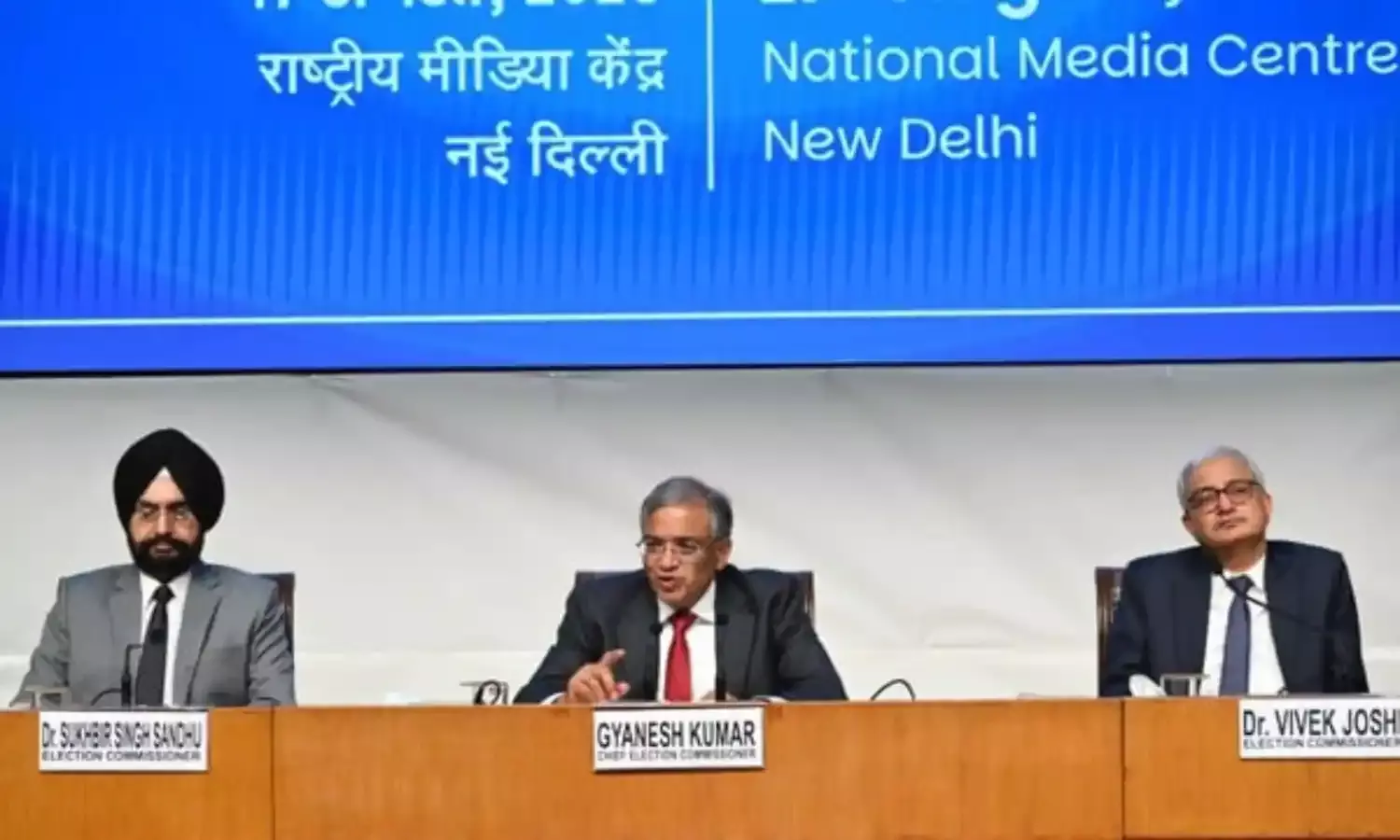

Against this backdrop, the Chief Election Commissioner’s (CEC) press conference on August 17 was keenly awaited. With the Opposition accusing the Commission of complicity in “vote theft,” expectations were high for clarity, reassurance, and accountability. Instead, what unfolded was a meandering lecture on the Constitution and the Representation of the People Act. For over an hour, the CEC spoke about statutory provisions and the Commission’s constitutional standing—while avoiding direct answers to critical questions.

Journalists pressed him on specific issues, but most responses were evasive. At times, they bordered on the bizarre. Asked about bias in voter verification, the CEC retorted: “Since it is the EC that registers the parties, how could it discriminate between them?” On why CCTV footage of polling stations was not released to disprove malpractice allegations, he claimed doing so would breach the privacy of “mothers, daughters, and daughters-in-law.”

He also raised his voice to emphasise that, as per the law, an election petition must be filed within 45 days. Beyond this deadline, any complaint of irregularity or mistakes in the electoral roll must be accompanied by an affidavit and evidence in support of the claim. But when reminded that the Samajwadi Party had indeed submitted affidavits in 2022, he flatly denied it—only for his claim to be later proven false.

Several other questions were dodged altogether. Asked whether the EC would investigate irregularities reported from states like Kerala, the CEC brusquely said, “Next.” He offered no explanation for pushing ahead with SIR in Bihar while the state grappled with severe floods. When pressed about faulty rolls, including dead voters and duplicates, he claimed that the electoral roll and the act of voting were two separate things. The statement left many incredulous: since votes can be cast only if names are on the rolls, duplicate entries could plainly allow multiple votes.

His refusal to provide a machine-readable list was justified with unconvincing reasons, even as he ignored mention of a Supreme Court order directing otherwise. Journalists also asked why notices were quickly served on Rahul Gandhi but not on Anurag Thakur for similar allegations. The CEC was silent.

The Election Commission of India has long been regarded as one of the country’s most respected institutions, celebrated for its ability to conduct free and fair elections under challenging circumstances. But in recent years, its actions—and silences—have come under sharper scrutiny. In today’s political climate, perception matters as much as reality. If the Commission appears evasive or partial, restoring public trust becomes far harder.

That is why Sunday’s press conference felt like a squandered opportunity. With the nation watching, the CEC had the chance to demonstrate openness and defend the Commission’s impartiality. Instead, the public was treated to a long sermon heavy on self-justification and light on answers. Rather than dispelling doubts, it reinforced the impression of an institution uneasy with transparency—and unable to shake off the charge that its conduct is not always even-handed.

Sandip Mitra retired from the Indian Foreign Service. Views expressed here are the writer’s own.