Can Roger Binny Fix BCCI's Troubles?

There is no magic wand that can make major changes in the working of the Board of Control for Cricket in India

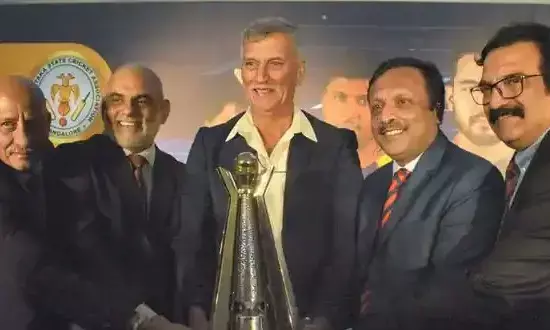

Roger Binny's appointment as president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has generated a great deal of goodwill. We have had articles in print and on the web hailing his qualities as a person, and as a player, and the general view that he is the right choice for the important post. There is a sense of déjà vu in all this.

I remember the mood was pretty upbeat even when Sourav Ganguly, Binny's predecessor took over as BCCI chief. Then too the experts praised his contributions as a player and being one of the outstanding captains in the history of Indian cricket, and expressed confidence that he would take Indian cricket to great heights.

Like Binny, he too was hailed as a no-nonsense person who had the stature to bring about welcome changes in the functioning of the BCCI. The upshot is that his exit has not been the kind he would have liked and the same experts now say that he didn't quite walk the talk.

There is really no magic wand that anyone can wave to make major changes in the working of the BCCI. There are any number of pulls and pressures, there are so many serious issues to consider that it is virtually impossible for the BCCI chief to function absolutely independently, much as he would like to.

Like Ganguly, Binny too is a strong willed person and seemingly has the qualifications, experience and credentials to take over the post. But whatever ideas he might have in bringing about changes once he takes charge he will increasingly find that he has to perform a balancing act due to circumstances and because of this a good deal of credibility could well be lost.

Personally, I have never really understood the specious argument that a former international cricketer would make the best president or secretary of the BCCI. A good cricketer at the top level means that he can play an elegant cover drive or bowl a well-disguised googly.

It does not automatically mean that he is cut out for any other aspect of the game and be a successful coach, administrator or mediaman These posts require certain dynamic qualities which not everyone has. There are so many international cricketers who have failed to make good in other departments associated with the game.

Besides a certain dynamism an administrator has to work hard at his desk to get things done. The international cricketer has the connections thanks to his excelling on the field of play and being a well-known personality.

However, off it while negotiating tricky financial deals or exchange of tours by other countries a certain diplomacy is called for. He must be excellent in public relations and be crystal-clear in communicating decisions. Not every player is capable of all this.

In my long career as a sports journalist I have moved closely with cricketers and administrators and the best of the latter are those who haven't played the game at the highest level. Some of them have not even played first class cricket but they brought to the table the most important quality to be a successful administrator – an innate love for the game.

Half-a-century ago there was virtually no money in cricket and none of the gadgets that are available today. But officials used to work hard at their paperwork and see that everything was in order.

Before taking any decisions or making any changes they would ask: 'will it benefit the game, will it benefit the players?'. That was almost sacred to them.

I have been fortunate to see at close hand the manner in which administrators like M. A. Chidambaram, S. Sriraman, M. Chinnaswamy and M. Thimmapiah carried out their work. None of them played cricket higher than club level but they were giants among administrators. Little wonder that two of them have international stadiums after them.

And in this regard can one forget Jagmohan Dalmiya and the respect that he earned for Indian cricket worldwide? He was the one who ensured that the veto enjoyed by England and Australia, the ICC founder members, was removed.

Again by skillful manoeuvring in the boardroom Dalmiya saw to it that India became the engine that drove world cricket. Malcolm Speed the former ICC chief executive once spoke of Dalmiya's "manic determination to make India a world cricketing power.'' Dalmiya forced respect from countries long used to looking down on Indian cricket. And I don't think he played the game at a higher level than club cricket.

Naturally we all wish Binny all the very best and sincerely wish that he takes Indian cricket to even greater heights. All I want to convey is that this fetish that only an international cricketer should head the BCCI must end.

Anyone who has been involved with the game in some capacity for years, has the required stature, be a good communicator, can get things done in his own dynamic manner, loves the game passionately and is willing to do anything for the good of Indian cricket qualifies to be the ideal candidate.