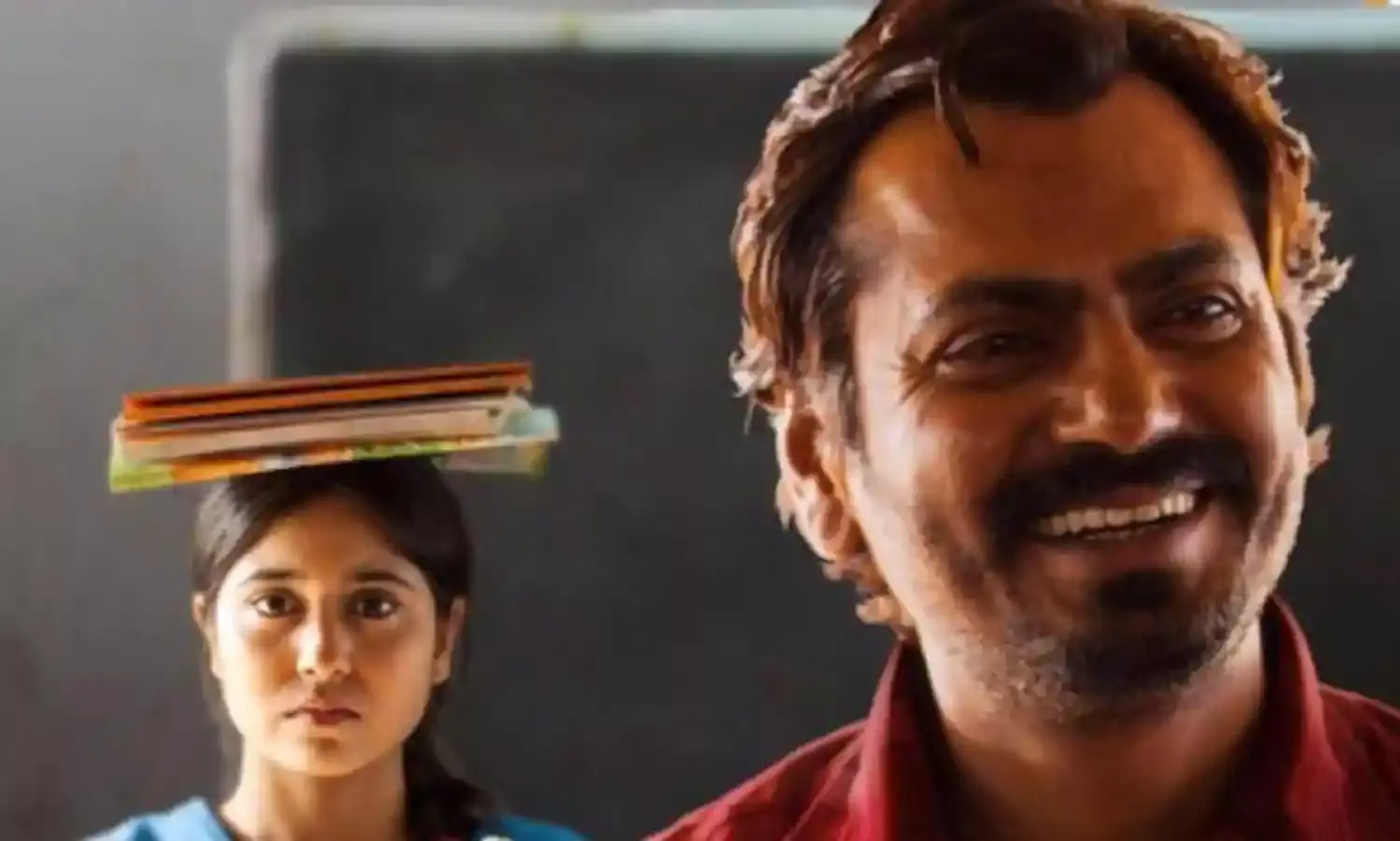

There is much more in An Ordinary Life than Nawazuddin Siddiqui's affairs with women.

MEHRU JAFFER reviews

There is much more in An Ordinary Life than Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s affairs with women.

The memoir of the 43-year-old award-winning actor is in fact a brave attempt to come to terms with life’s gifts, including different shades of love, wealth, and above all success. Clearly one of the busiest and most popular actors in the country today, Nawaz took time out to put this book together as if to find out how true he is, at least to himself.

“Sometimes I wonder why people like my work so much. One reason could be because I try to understand, and to portray characters honestly. My biggest challenge is to remain as honest as a human being possibly can be, in life. And on screen I want to be as truthful as nudity is,” Nawaz told The Citizen in an informal conversation on the sets of a film in Mumbai.

The book offered him a golden opportunity to explore his difficult relationship with Abbu Nawabuddin, his father. He recalls what it was like growing up in a large joint family in a little part of rural India in western Uttar Pradesh where the traditional profession of farming is threatened. In his lifetime the late Nawabuddin was reduced to running a carpenter’s shop due to the abolition of zamindari and feuds within the family.

The son writes:

“I walked in and told Amitabh Bachchan…” Abbu said.

“What did you tell Amitabh Bachchan, Abbu?” we begged in suspenseful chorus.

“I said, ‘Now you wont be able to do films, Bachchanji, right? You are in politics now.” Amitabh Bachchan replied instantly, ‘Arey, Nawab Sahib, ab kahan filmein. Ab to sirf politics!’”

I latched on to every word, awestruck. If my Abbu could meet Amitabh Bachchan, then he could do anything. However as I grew up and became mature, the falseness of his anecdotes began to strike me the moment he would begin narrating. What a small man my father is, I would think. He tries to become a big man based on lies. Soon though, I realized how desperate he was. And instead of hating him, I began to love my father even more for his lies. All Abbu wanted was to be a hero in the eyes of his children, even if he was a failure in his own eyes and in the eyes of the world.

We get to know how delicate religious and caste relations are in this part of the country. His paternal grandmother was a Manihaar, a community of bangle sellers belonging to the scheduled caste, and for decades the family suffered discrimination due to this love marriage with a lower caste person.

On one side, my grandfather was a zamindar, which automatically entitled us to pride and respect. On the other hand, my grandmother’s low caste background gifted us shame. It was a cruel oxymoron for a family to exist in. For my father, this was a shadow that accompanied him everywhere lifelong, right from birth.

We are introduced to his mother whom he adores:

Ammi used to beat me a lot. I used to stay out all day, playing all kinds of games-kanche (marbles), gulli danda, and my favourite, flying kites. Ammi wanted me to study while I just wanted to play.

He questions success. He wants to know what is a star? It is an image. It’s easy to be that created image. It’s hard to be an actor.

Elsewhere he says:

But I don’t want to be a superstar. I don’t want people to watch me. I want people to watch my craft. If they watch a Nawaz film, I want them to focus on the craft. How did he do this role?

Now that he is in a position to do so, Nawaz wants to go where no actor has gone before. He wants to do every role possible. He wants to live as many lives through his acting as there are grains of sand on a beach or stars in the patch of the night sky above his terrace.

After all, we have only one life, one tiny life to live. And one lifetime is way too short to do all of this. I will do as much as I can. I will pack in as many people, as many lives, as many roles, as many shades as I can into this one lifetime as an actor.

There is an entire chapter on his mentor Anurag Kashyap who is in love with Nawaz’s eyes. He calls Nawaz his ‘item girl’.

“We keep clowning around, but seriously, if either one of us was a girl, we would have married each other. I am his muse, he says, and he is mine, I tell him,” Nawaz writes.

The memoir is filled with numerous delightful anecdotes such as this one. Nawaz talks at length about his days at Lucknow’s Bhartendu Natya Academy (BNA) and Delhi’s National School of Drama (NSD) with immense affection, gratitude and pride. He mentions teachers and colleagues who have influenced him. He names plays that have inspired him. We get to know why Nawaz now prefers cinema to theatre.

Because there are so many tiny nuances, countless subtleties that theatre cannot depict no matter how hard it tries.

When Nawaz leaves his large family in the village and travels to Mumbai by himself, he is soon attracted to a community of people who like him are struggling to find work in the film industry.

Our little tribe of struggling actors grew, and in spite of our cruelty, insanity and selfishness, we were together. It became a sort of a dysfunctional family. We strangled each other, but also looked out for each other in strange ways.

I feel lucky to have read, and to have enjoyed this book and feel sorry for millions of fans unable to feast on the fascinating journey of this great actor. This is because the book is no longer available in the market. It was released on 25 October and taken off the shelf last week after the author tweeted an apology for hurting the sentiments of some women mentioned by name in An Ordinary Life.

“I am apologizing to everyone whose sentiments are hurt because of the chaos around my memoir An Ordinary Life I hereby regret and decide to withdraw my book,” read the tweet. What extraordinary shame.