Kadak Singh Is Not About Warm Fuzzy Relationships

Thriller Or Family Film?

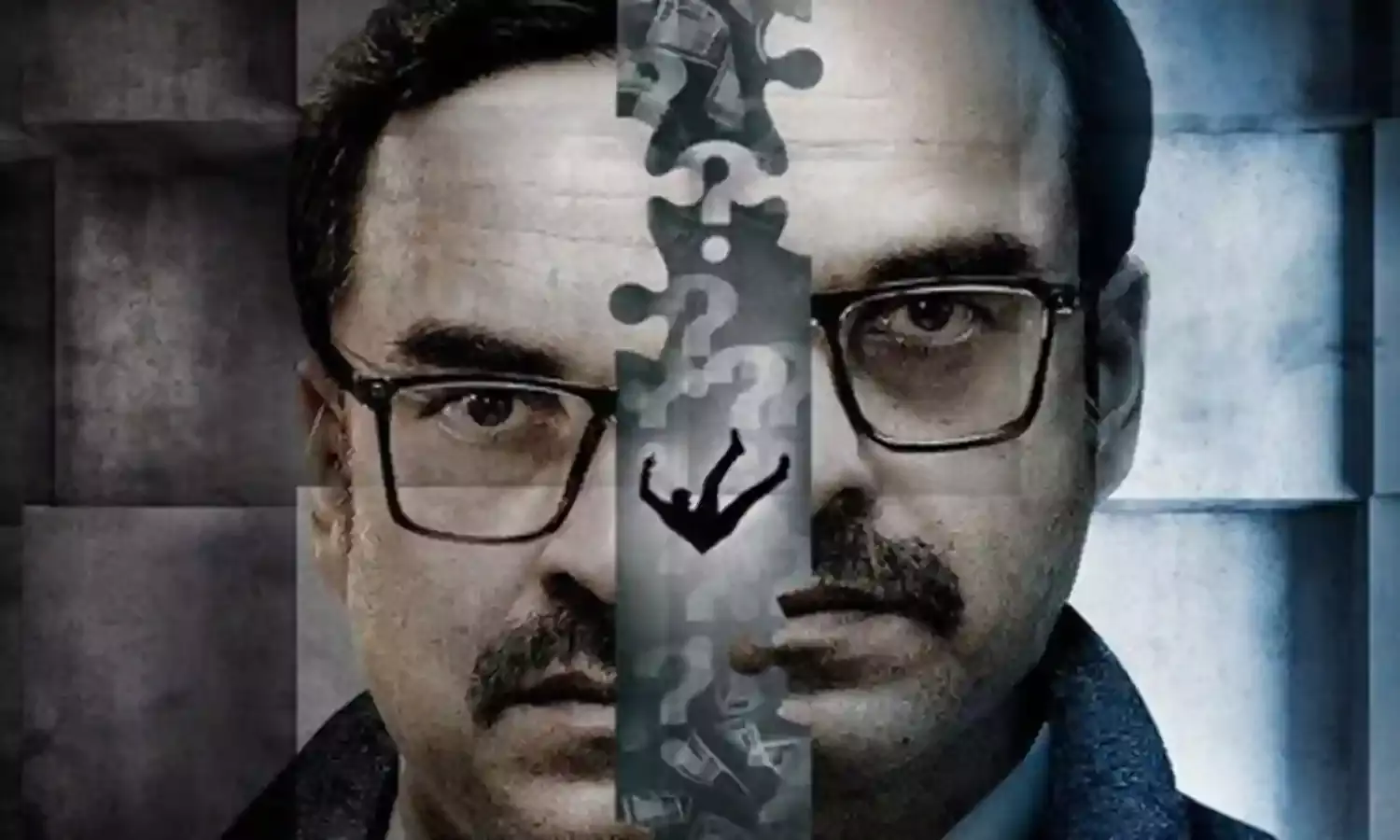

‘Kadak Singh’ is what A.K. Srivastava’s (PankajTiwari) children call him behind his back. it throws up heavy hints of the film belonging to the ‘relationship’ genre. But halfway through, it becomes a thriller, a genre director Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury seems to be fond of.

But is there a problem with multiple genres in the same film? Yes, and no. Yes, because Choudhury has honed his directorial and writing skills with the thriller aspect, and no, because the ‘family’ angle does not quite work, except in the end when all corners are rounded off, and everything ends happily ever after. But does it?

‘Kadak Singh’ opens within the spacious room of a posh hospital where the protagonist, Srivastava, an honestofficer investigating a financial fraud case, is recuperating from a suicide attempt. He suffers from retrograde amnesia caused by the trauma. His grown daughter Sakshi (Sanjana Sanghi) is trying to convince him that she is, indeed, his daughter but Srivastava refuses to acknowledge her. His memory tells him that he has just one son named Aditya and demands to see him.

The flustered young girl tries to persuade her father by telling him what has happened to him. But an apparently healthy and cheerful Srivastava, showing no signs of illness, enjoys his daughter’s spiel as if he is listening to an ‘entertaining’ fictional story. One cannot call this a father-daughter conflict as the father does not remember she exists, even as the daughter is desperate to bring him out of his amnesia.

The success of the film lies in its raising questions one after another. Each throws up several possible solutions without arriving at a single answer. What happened to A.K. for him to forget many things of his life? Why did he attempt suicide? Was it really suicide or was it an attempted murder? If so, why would anyone attempt to murder him? Who is/are the culprit/culprits? These answers are withheld until the end.

These questions that take the story forward are enriched by Pankaj Tiwari’s powerful performance as A.K. He enlivens the proceedings with his humour and deceptively light-hearted way of handling situations. His shock when one of his colleagues commits suicide shows another facet of A.K..

He finds a compatriot of sorts in his 24-hour care-attendant (Parvathy Thiruvothu). She is an acute observer of whatever goes on in this cabin, without commenting but only throwing caustic looks at A.K. and at his visitors. This adds some masala to an otherwise tending-to-be-dull proceedings.

As one of the most dedicated and honest officers at the Department of Financial Crimes (DFC), A.K. does not appear to be worried. His sole worry is to find out what happened to him and why and his memory lapse fails to provide answers. His son Aditya is recuperating in a drug de-addiction home but A.K. has no memory of where he is, demanding that he be brought to meet him at once.

The characters are well fleshed out, and the deceptive facades of those involved in the massive financial crime that places the department in great danger, are scripted tightly. Arjun (Paresh Pahuja), his trusted aide, Mr. Tyagi (Dilip Shankar) his boss, and the rest handle their roles with conviction. The electrically charged tension, as the incidents rush through the past, before A.K. lost his memory is well-handled.

But what brings the film down several rungs is the intriguing relationship between A.K. and the charming Naina (Jaya Ahsan). However, Ahsan offers a beautifully subtle and restrained performance in a longish cameo.

Naina is not given any backstory and suddenly surfaces like Cinderella creating a façade of a platonic relationship with A.K, calling it a “deep friendship”. This creates the most absurd phase in the story as widower A.K. shares hours with Naina in hotel rooms, covered in white bedsheets with parts of their entangled bodies peeping out enticingly from underneath.

Though this allows for some titillation in an otherwise romance-free film, it fails to work. It leaves us to ponder on how Sakshi comes to terms with the relationship, and becomes Naina’s friend. How convenient. Naina also labels it “political sex”, and we are left to ponder what it means.

There is a melodramatic scene of a street argument between the father and daughter, when the latter sees the father walking with a strange woman, and suspects the worst. It is melodramatic because it later turns out to have been a manipulated situation, to create further conflict between father and daughter.

The editing is brisk, which helps the otherwise sluggish pace of the film. The background score, however, is a bit on the loud side. The soundtrack misses out on the ambient sounds of a hospital. The pace suddenly picks up after A.K.’s attempted suicide, and it seems as if the film is in a tearing hurry to reach the finishing line. The cinematography relies on shades of blue and gray, steering away from primary colours.

Kadak Singh does not offer a linear narrative but moves fluidly between the past and the present, which is one of the integral features of suspense. Cinema has the ability to manipulate time in exceptionally diverse and precise ways. Roychoudhury has the skill to manipulate the factor of time, in which anticipation and protraction are key factors. He has already shown it in his earlier films like ‘Piku’ and ‘Lost’.

Kadak Singh is not just a terrible name that A.K’s children call him behind his back. It is connotative of his nature of honesty, commitment and sincerity which leads to the tragedy that befalls him. He laughs, jokes and is cheerful even in the hospital. And as far as the financial scam in his office is concerned, he remains as ‘kadak’ as he is known to be. Watch the film as a psychological and financial thriller. Not like a ‘relationship’ film.