A-I Will Aggravate Targetting of Women and Vulnerable Groups On The Social Media

Identity fraud using deepfake technology

Indian journalist Ghazala Ahmad was left shocked when she received calls from concerned friends informing that her name was on the list called “Bulli Bai”, which was doing rounds on social media. By the time the 28-year-old journalist could gather her senses and logged onto social media, everything was removed by the concerned authorities.

In July 2021, an app called “Sulli Deals” surfaced, reportedly allowing men to ‘bid’ on the profiles of featured Muslim women. The women on the ‘list’ were prominent figures within their respective professions. The women ‘listed’ included journalists, social workers, students, and well known online personalities.

The app, hosted on GitHub, functioned only to humiliate the women who were named on it. After sparking public outrage, GitHub suspended the account.

GitHub, Inc. is a developer platform that allows developers to create, store, manage and share their code. It uses Git software, providing the distributed version control of Git plus access control, bug tracking, software feature requests, task management, continuous integration, and wikis for every project.

However, the Delhi Police were slow to open an investigation into its founders. In January 2022, another app, called “Bulli Bai,” emerged on the same platform, also containing photos of Indian Muslim women, accompanied by derogatory content.

Ahmad’s name was included in the list. The Indian journalist is known for her breakthrough stories, particularly on communal violence.

“I know that my identity as a Muslim woman and a journalist was the reason why my name was on the list. My work is for the people and I want to report the injustice they are going through at the hands of those in authority,” she said.

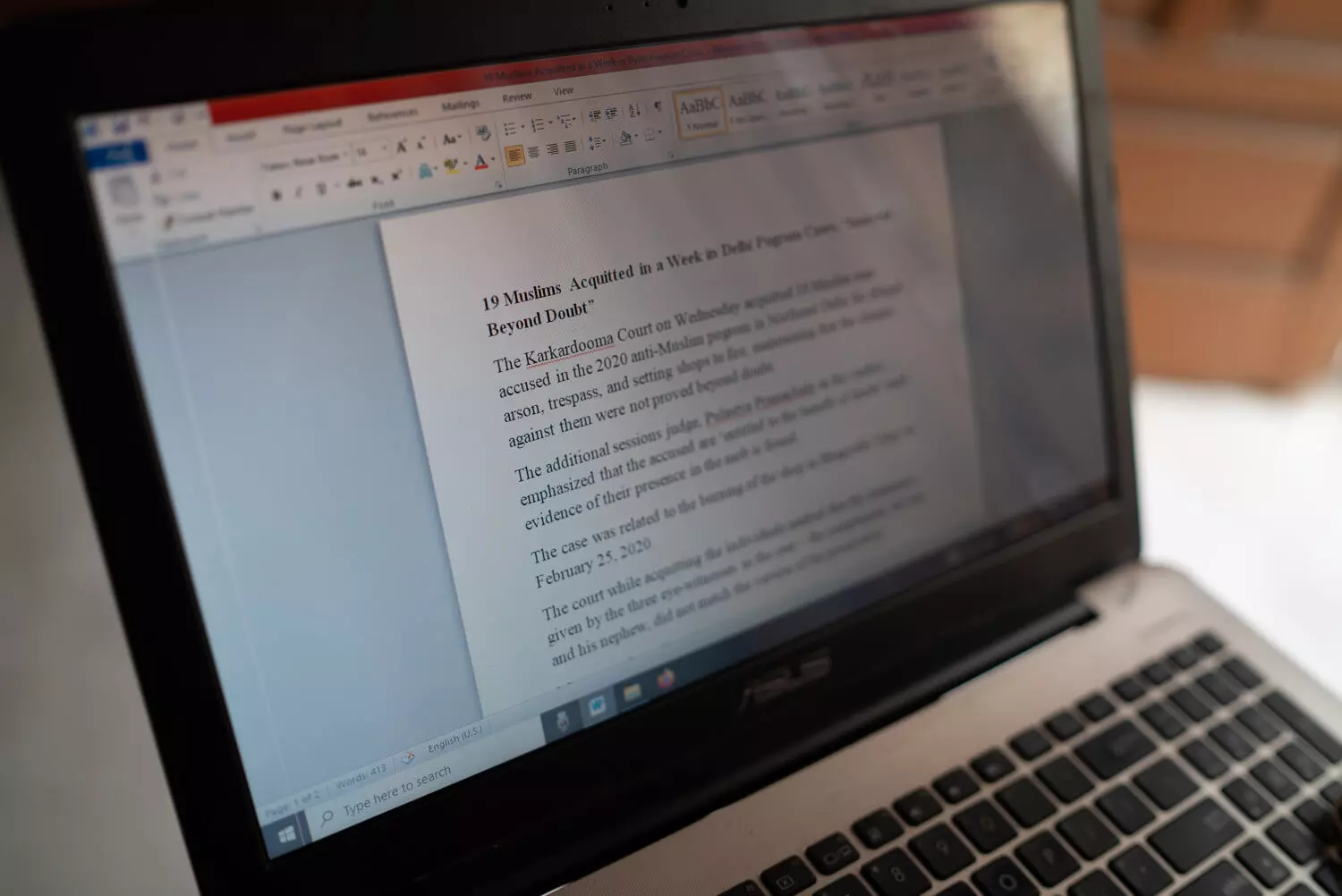

After a massive social media outrage, with people coming in support of the women, six people were eventually arrested in connection with both cases. However, all were granted bail later.

“I am thankful that I did not see my name directly, but it was humiliating as everyone else did. There was a time when this impacted me very much, but then I decided that my work is more important,” said Ahmad, who hails from India’s northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

Ahmad pointed out that social media has become a hub of Muslim hate in India. From hate speech to fake information, Indian social media has become the leading source of black propaganda, according to various reports.

Ahmad who also works on busting such fake news and malicious disinformation, said that with the increase in content from India, there are only few organisations working towards exposing it. However, the journalist said she was not surprised looking at the polarisation the country has gone through.

The ‘Sulli Deals’ and ‘Bulli Bai’, both derogatory terms used for Muslim women, were just a series of attacks against the Muslims in India, who are facing a genocide-like situation in the country.

According to a report by Hindutva Watch, a Washington-based group monitoring attacks on minorities, anti-Muslim hate speech incidents in India averaged more than one a day in the first half of 2023 and were seen most in states with upcoming elections.

The report stated that there were 255 documented incidents of hate speech gatherings targeting Muslims in the first half of 2023.

Hate crimes and speeches against India’s religious minorities, including Muslims, who account for 14% of the country’s 1.4 billion population, are on the rise. While on ground the situation becomes worse, fake information and propaganda against the minorities is spread on social media.

“There was a time when I could not sleep as I kept working on dissecting or finding hate speech on social media. The sort of statements political leaders and even common citizens made was so disturbing that I went on an obsessive investigative spree. My family and friends around me got concerned but all I could think of was the hate that was being spewed against Muslims online,” Ahmad said.

Since October, amid Israel’s continuous bombardment in Gaza, a lot of anti-Palestine and Islamophobic content has been shared on social media. According to various reports, most of the disinformation came from India’s right wing social media.

As India gears up for 2024 General Elections, there are concerns regarding the rise of social media hate and harassment campaigns, which always peaks around elections, especially against Muslims.

Experts have time and again pointed out how India is moving towards genocide against Muslims where social media has been a major weapon by the Hindutva ideology brigade.

According to Professor Noam Chomsky, one of the world’s leading public intellectuals and Professor Emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Islamophobia is taking its most lethal form in India, with almost 250 million Muslims in the country becoming a persecuted minority, attacked both offline and online.

This is where incidents like “Sulli Deals” come in. Attack on Muslim women’s identity whether it is the hijab ban or attack on them online, experts feel that it is all part of “humiliating” women who are vocal about the issues.

Indian writer Sara Ather, who has been at the receiving end of the attacks from right-wing Hindutva trolls, told the correspondent how religious and hateful slurs against Muslims are overlooked by social media platforms.

“I remember a few months back I was looking at some of the words that are Muslim slurs and tried reporting some of these on Instagram but failed as it would not go against the community standards,” she said.

Witnessing a whole lot of harassment almost every day that takes a toll on one’s mental well-being, Ather said that the social media algorithm also works in favour of the oppressors.

“Words used against Muslim women, for example, are never even looked at as something that is derogatory. And if someone is trying to report them, then there would not be any significant action taken by these social media platforms as, most of the time, the algorithms themselves do not read it,” she added.

While social media is being used to such an extent, use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), especially by the authorities to attack minorities have started concerning the Indian civil society. With AI becoming a foremost technological support globally, India has also tried to adapt the technology in various ways.

The Indian government has gradually started making provision for its use and implementing it in education, criminal, health and agricultural sectors.

India’s status of being a country with 1.4 billion powering the world’s fifth-biggest economy, has led to the questions of whether AI will be used morally.

Speaking about AI in terms of criminal policies, Nikita Sonavane, co-founder of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project, a non-profit organisation, pointed that the technology will further aggravate the already discriminatory institution.

“The way technology is being deployed now in the context of criminalisation and policing across the board, I don’t see it as an aberration or being exceptional in terms of the history of these institutions, which has always been violent and discriminatory and is woven into the designs of these institutions,” she said.

Sonavane while talking about the use of AI in policing or law enforcement systems averred that she sees technology as being adapted to around institutions and frameworks that have always been discriminatory by design.

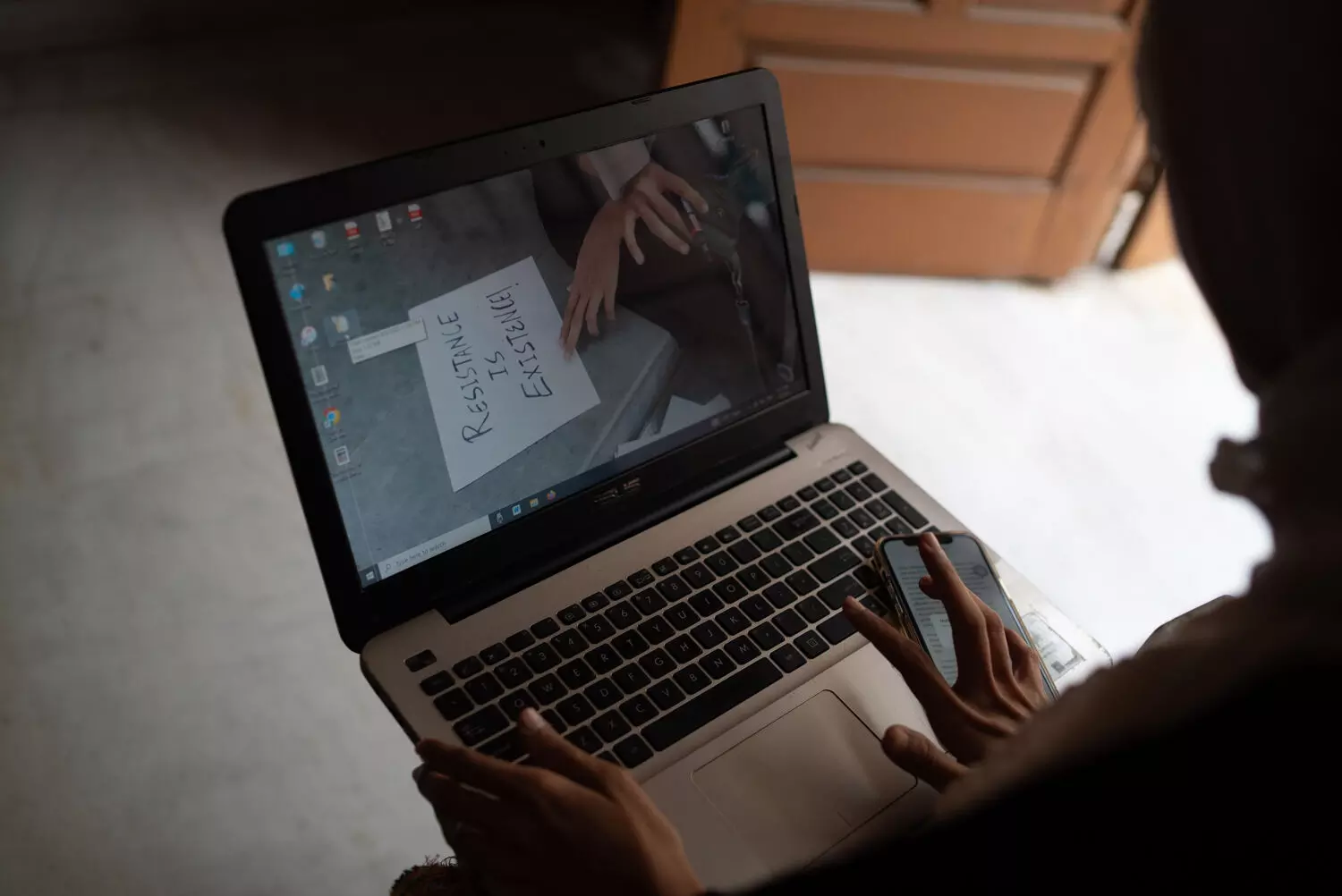

In 2020-2021, during the crackdown of activists, post violence in different parts of the country, as many protested the Anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), facial recognition and CCTV was used to arrest people who were part of the dissent. The protests occurred in different parts of India at the end of 2019, when the Indian government introduced the bill.

The move sparked widespread national and overseas protests against the act and its associated proposals of the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

The CAA amends the Indian citizenship act to accept illegal migrants who are Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Parsi, Buddhist, and Christian from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, and who entered India before 2014, following the religious persecutions. The Act does not mention Muslims and other communities who fled from the same or other neighbouring countries. Refugees from Sri Lankan Tamils in India, Rohingyas from Myanmar, and Tibetan refugees are also not mentioned in the bill.

Among those arrested was student activist and scholar Safoora Zargar. Zargar was arrested in April 2020. The 30-year-old is still reeling with the aftermath of her arrest that changed her life.

At the time of her arrest, Zargar was over three months pregnant. Her case at the time created an uproar as many from the civil society averred that there was no concrete evidence against her.

“It feels like you are guilty until you are proven innocent. So, for me, fighting this case and going through this trial is about the same. It is because we have already been stamped as terrorists,” Zargar said.

On March 6 2020, the Delhi Police’s Crime Branch invoked against them various sections of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), India’s draconian anti-terror law.

During her arrest, social media was filled with fake information regarding her personal life, including her marriage. Right-wing trolls bombarded Twitter and various social media with nasty posts about her wedding and pregnancy.

Despite all the information getting debunked, fake images and personal information were already spread by the trolls. Since then, such incidents against Muslim women have become common.

One of the major concerns raised by tech experts is the use of deepfake and how it is being used to attack women. While deepfake is used by estranged men, who make videos of their former lovers or ex-wives, as a way of “revenge porn”, in India it is also being used as a political tool against leading political and social voices against the unruly regime.

In May 2023, morphed photos of Indian women wrestlers, who were protesting against sexual harassment, arrested by the Delhi Police after they tried to march towards the Indian Parliament in India’s national capital, were circulated.

Social media was filled with fake photos where Indian medal winning wrestler Vinesh Phogat was seen smiling as she was detained and sitting inside the police van.

Later, two photos – one morphed and the other real – were shared on X (Formerly Twitter) as a fact check. In the original photograph, the wrestler along with other detained wrestlers have serious expressions.

With its 800 million internet users, India is becoming the center of a deepfake epidemic with some commentators now wondering whether the technology could affect its general elections scheduled between April and May 2024.

Besides India, Bangladesh and Pakistan are the countries that are ranked among the top ten in the Asia-Pacific as most impacted by identity fraud using deepfake technology, according to the 2023 Identity Fraud Report from digital identity verification firm Sumsub.

While digitally manipulated images and videos of women were once easy to spot and were usually found on dark web, the explosion in generative AI tools such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and DALL-E has made it easy and cheap to create and circulate convincing deepfakes.

In Zargar’s case too, fake information about her personal life along with morphed photos were shared on social media, not only degrading her amidst her arrest, but also spreading false information about her.

The trauma that Safoora still suffers with has taken a toll in her life. “I was forced to leave my PhD as the university kicked me out. I can’t travel, even to meet my parents, without informing the officials. All this is a collective punishment in itself,” she said. Zargar’s case is ongoing with many others, few who are still in jail.

A recent study by The London Story (TLS), a diaspora-led foundation in the Netherlands working to combat disinformation and hate speech online, revealed that Facebook, which is the world’s most popular social media platform, hosts and promotes “a disturbing volume of direct hate speech, disinformation, and calls to violence against minorities” – particularly those of Muslim faith.

This kind of content is more dangerous in India, TLS observed, which has Facebook’s highest number of users and has a massive consumption for news and propaganda, and where violent far-right voices have become more mainstream due to amplification on Facebook and its associated apps.

“There is so much fake news that is taking rounds and despite the few organisations in India that are doing the fact checking, there are no attempts by the platforms itself when the thing has been proven false,” said Ather.

In times of change in India, tools like facial recognition and CCTV surveillance are only being used as a policing method, especially with a government that is hell bent on using AI against crime.

Last year, the UK-based cybersecurity website Comparitech said Delhi was the most watched city in the world in 2021, with 1,826 CCTV cameras per square mile. Cities in China have since taken over, but Delhi remains among the ten most “surveilled” cities in the rest of the world, alongside the likes of Singapore, London, New York and Los Angeles.

And while this has been hailed as an achievement, legal experts find the situation troublesome. It is not just Delhi, but states like Telangana, where the use of CCTV has been questioned by the civil society.

“It is important to talk about these existing systems, whether it is criminal hotspots, or CCTVs. These are all systems embedded into existing frameworks. The thing is in order to map the crime, you have already narrowed down people and spaces, and what this system is doing is showing up the same result,” Sonavane explained how discriminatory these tools are.

She said it is imperative to understand that the framing of these institutions is casteist and Islamophobic in nature.

Pyone Cho, Education and Communities Coordinator at Access Now, a non-profit organisation founded in 2009 focused on digital civil rights, said that the problem lies with the fact that we ourselves feed the data to this concerned software.

“When we talk about face recognition or even AI, the first thing is we have to feed data to them, as they have to learn from the data sets. For example, when the government uses face recognition and the biometric data, we are the ones who gave our data in the first place,” Cho said.

From registration of SIM cards to filling details online, we are giving our information, with consent, to the government. He further said that the demand for data in South Asian countries has become fairly common and is being forcefully taken by the authorities.

“For the online platforms, for example, we have to give our biometrics. For example, in Myanmar, the company has to give out the rules and regulations while taking data, no matter what. It is important to follow the rules and regulations implemented by the current government. But if these corporate organisations are claiming that they are not giving out data, they definitely are,” he said.

(This story was produced as a part of Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development’s Media and Visual Fellowship on Militarism, Peace and Women’s Human Rights.)

( Photographs By Bhumika Saraswati)