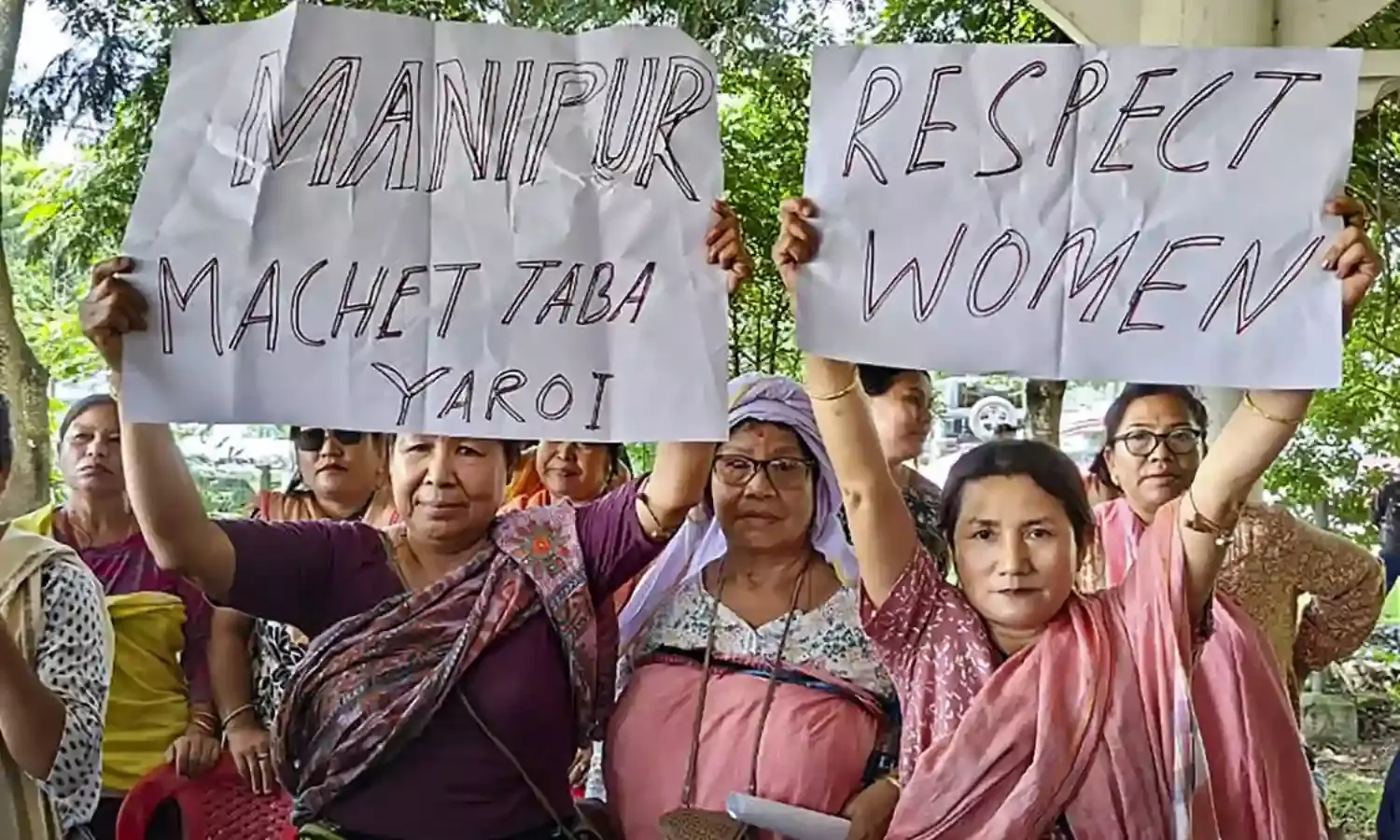

Women Are Targets in Conflict Zones

Unimaginable Trauma Binds Victims of Sexual Violence

The reports of the ghastly sexual assaults on Manipuri women makes one recall some of the most heinous cases of sexual violence that have dotted the Indian landscape in the last two decades. These are cases that have become a blot on different state governments, have at times become inter-state issues and have also shown the Centre in poor light. They have also damaged the country’s reputation abroad.

The thread that binds them all is the failure of the State to protect its women. What has emerged time after time is a matter of shame for the authorities.

If one talks of the North East that has been witnessing ethnic strife for decades, one can recall the infamous Piphema rape case of 2002 where a girl was allegedly raped and another was molested in the middle of the night while they were traveling in a bus on National Highway 39. The incident had become a major inter-state issue between Manipur and Nagaland where the intervention was sought from the Union Home Ministry.

No one can forget the rape and murder of Thangjam Manorama Devi in 2004 in Manipur, which is again on the boil now. It made international headlines when a group of elderly women reportedly stripped themselves in front of the 17th Assam Rifles headquarters calling the army to rape them just as Manorama had been raped.

These elderly women were from ‘Meira Paibi’ or Torch Bearers organisation. The state had subsequently erupted in violent protests against the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).

As these cases of heinous sexual assault are being discussed, memories rewind to the Gujarat pogrom of 2002 where numerous such assaults were reported. A case that stands out and is being referred to again and again in context of the present one emerging from Manipur is that of Bilkis Bano.

The ghosts of the Bilkis Bano case have returned to haunt the nation’s conscience. Barely a year ago the release of the convicts and the heroes’ welcome accorded to them, had made the headlines.

Another instance that comes to light is the reported gang rapes at Murthal at the height of the Jat reservation stir in 2016. The case remains a mystery till date, and despite the Punjab and Haryana High Court pulling up the government things have not moved ahead.

And of course no one can forget the outrage witnessed across the states over Delhi’s Nirbhaya case.

It is the common thread of complicity that binds several of these cases. These instances fly in the face of claims about an ancient civilisation and India being a ‘Mother of Democracy’.

For a journalist covering such cases is one of the most difficult of assignments as the trauma that these victims undergo is unimaginable. This trauma cannot be quantified.

For me 2002 is the landmark as it was the worst that I covered as a journalist in the years that followed the Godhra train burning in which 58 Karsevaks returning from Ayodhya were torched. What had followed was a large scale anti-Muslim pogrom with violence in all forms.

I could never gather the courage to look at Bilkis Bano in her face while recording her quote for an international radio network. She related the threats given to her by medical professionals on being taken for a medical examination to establish sexual assault on her. “I was asked what I could do if they injected me with poison,” she had said.

The words of Bibi Bano of Naroda Patiya also continue to echo in the ears as she had related the horrors of what women had undergone in the round of violence. “Tanha nange aaye the bahut log Civil Hospital tak… (many women had reached the Civil Hospital stark naked, and alone),” she had recalled after her deposition before the Justice GT Nanavati and Justice KG shah Commission.

Another shrill voice that continues to ring is that of Sheetal Dhobi who had related how she was threatened day in and day out as she went about her daily business in Gomtipur. “Kabhi bhi utha lenge (we can pick her up as and when we want)… I get to hear these threats. I have been complaining but no one takes me seriously as if my dignity does not matter,” she had related after a similar deposition.

I can still recall struggling to remain calm in the presence of a victim couple. The baker from eastern Ahmedabad had witnessed his wife being raped before his eyes while a burning tyre had been placed on his back. They were struggling to move on with their two toddlers.

Then there was another interaction with a victim where she was on the verge of being hysterical saying, “I am asked to find solace in spirituality and religion. How can I? It was my religious identity that got me targeted.”

There have been so many of these cases that have been made to be forgotten. A similar trauma is getting played out in Manipur today. The pain of the victims is the same whether they are from any community. Trying to understand the trauma of a victim of sexual violence is a very daunting task.

“There is a complete sense of helplessness in the victims of sexual violence as they have complete faith in the official machinery that is betrayed. Helplessness and cynicism sinks in as the healthcare system is not equipped to deal with their trauma.

“We have witnessed the state getting away with impunity. Once again we are witnessing so many letters and representations being sent to the President of India.

“Thankfully the Supreme Court has come out with a strong direction on Manipur. Otherwise the various commissions that are supposed to address the human and other rights of women stand politicised to the extent that they do not fulfil their functions and act like the arms of the state.

“Where is the record for justice? Has there been any justice?” questioned Vadodara based Renu Khanna who is an activist with SAHAJ. She has done some commendable work on sexual violence and its impact on the victims in Gujarat.

The impact of such violence, be it in any corner of the country, remains the same.

On the question whether anything has changed between the previous cases including the Gujarat pogrom of 2002 and Manipur violence of 2023, she said, “There is more reporting and outcry because of the social media. But the efforts to divert the issue at hand, suppression of facts and denial by those in power remain the same.

“Ghettoisation is being promoted. Politically the divide between the people is being normalised. We don’t want to live in ghettos.”

In her paper ‘Communal Violence in Gujarat, India: Impact of Sexual Violence and Responsibilities of the Health Care System’ that was published in an online journal in 2008, she has pointed out, “The effects of sexual violence in Gujarat resemble those seen in other situations of conflict, including particularly the physical impact as well as the psychological and social effects of rape upon the victims, their families and the community.

“Women experience trauma to reproductive organs, deaths in childbirth, miscarriages and difficulties giving birth, a rise in and dangers of illegal abortions, sexually transmitted infections, possibly leading to HIV infection because of tears in genital tissues and the resultant bleeding, especially due to gang-rape.

“The psychological and social effects of rape are devastating. Terrified of being divorced, ostracised, infected with HIV or abandoned by their families, survivors cope as best as they can with their mental health problems in silence and isolation.”

She has mentioned that many women were killed after being raped and mutilated. Those who survived reported gruesome sexual violence.

The paper states that a large majority of survivors did not register rape complaints with the police. “This is hardly surprising, given the hostility of the police and the wrong recording of even the simpler First Information Reports.

“The police were hardly going to encourage the registering of sexual crimes. Additionally, deeply internalised notions of shame and honour prevented women from registering their complaints.

“So while there are no official figures of the number of women subjected to sexual crimes, women’s groups estimate that a minimum of 350 women must have been assaulted and raped,” the paper states.

She pointed out the varied and multi-dimensional consequences of such violence. “In addition to the obvious physical injuries inflicted by burns, arms and weapons, there were considerable mental trauma and stress, as well as hunger due to curfews, isolation and hiding, and infections and epidemics due to living in inhumanly unsanitary conditions of refugee camps,” she said while also listing the psychological threats.

Her work puts things into a perspective as she underlined, “Conflict and war have existed through history, and rape and other kinds of sexual violence have always been used as weapons to subjugate the ‘other’.

“However, in the post-colonial period, because of majoritarian nation–state building, violent struggles and military repression have increased in multi-cultural and multi-ethnic countries of the world.Resurgence of conflicts over ethnicity and nationality, politicised religion, globalisation-driven economic policies, revolutionary class struggles, separatist and autonomy struggles and the general failure of the democratic agenda, have all contributed to radicalised politics.

“Smaller groups are asserting their right to cultural survival and political power, and seriously challenging the state as the sole source of legitimate political power, along with the concept of the state as a neutral umpire.”

The document also states, “Technology and the strategy of annihilation have resulted in

wars not simply being fought on the “front” and among combatants, but with increasing severity in spaces and methods that target ordinary civilians. Sites of confrontation with the ‘other’ are the marketplace, the school, the community well or the water tap.

“Institutions of the State (such as the police and to some extent even the lower judiciary in India), are subverted to further the divisive agenda of the State. The objective is to destroy the social fabric of society, and the strategy is to create institutional terror, to permeate social relations and psychologically demoralise the community by creating suspicion and hatred.”