‘Hate! This One Word Alone is the Fruit of the National Movement’

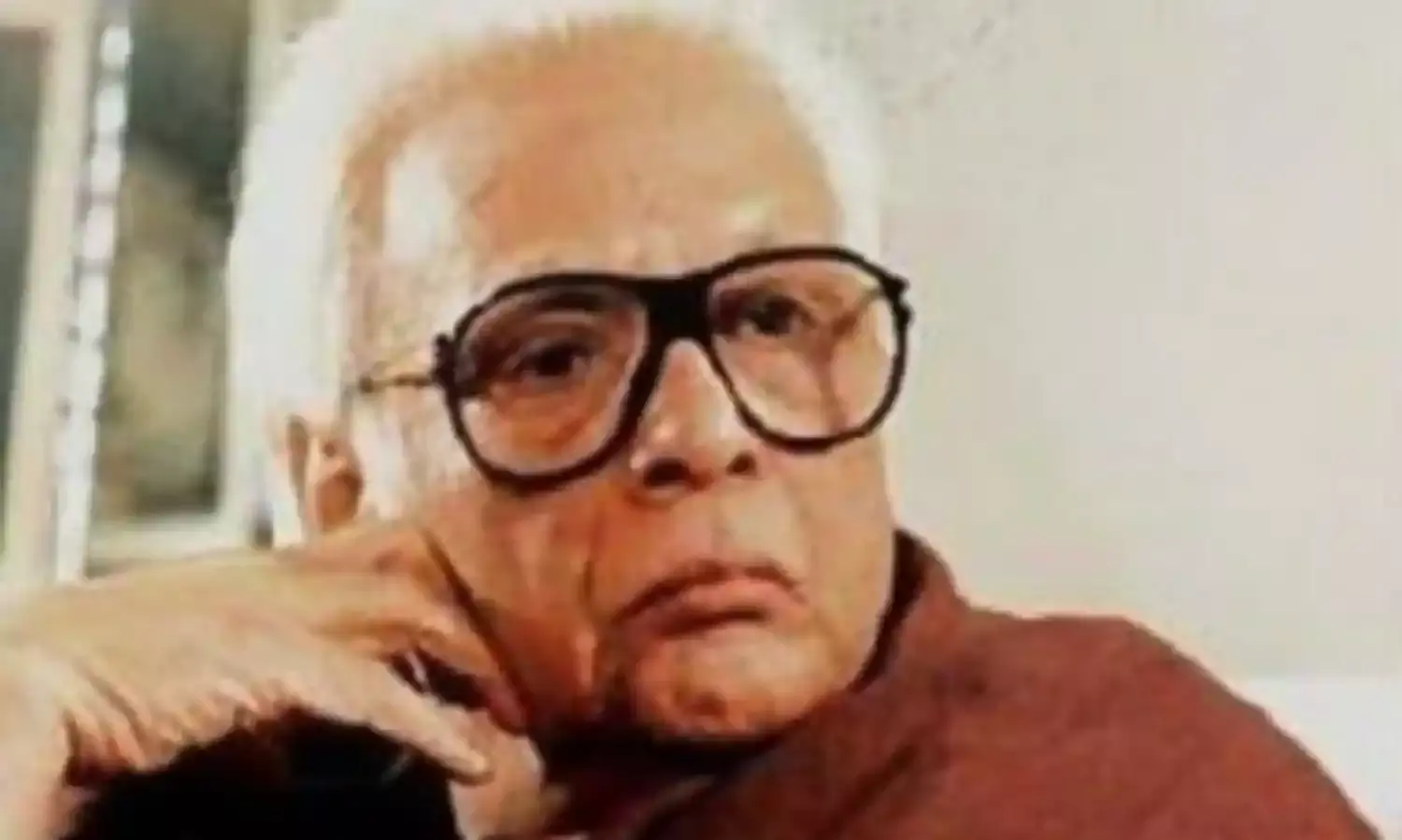

Remembering Rahi Masoom Raza (1927–1992)

In the body of Urdu-Hindi literature after Partition, the late Rahi Masoom Raza appears as one of the dominant voices in Hindustani literature. He comes into our public discourse at a time when human relations, especially between Muslims and Hindus, are sorely flunked.

Rahi dared to shape a generation post Partition. For him the partition of India was marked by a religious and communal idiom. Throughout his oeuvre he assigned himself to touch upon the issues that haunt Hindu-Muslim relationships.

His ideological underpinnings (a secular and versatile humanity) saw a great deal of what goes on in the everyday life of people, and how people constitute their meanings, making sense, in everyday social engagements, of the partition of India.

He was of the view that people often choose their everyday behaviour from historical anecdotes.

He composed the script and dialogues of the famous TV serial Mahabharata. Many of us grew up with the profound echo of “Main samay hooon…”

Presciently he proposed that the partition of India was not the end of a problem, but rather the beginning of an era of communal politics in India. That it would provide plentiful space to the divided communities to craft their respective glorifications.

“I belong to three mothers,” he wrote, “Nafisa Begum, Aligarh Muslim University and Ganga. This book Scene 75 is dedicated to them. Nafisa Begum is not alive so I don’t remember her exactly, but the other two mothers are alive and I know them very well.”

Here the river Ganga is a metaphor for being a believer in a common and shared history. Rahi is conscious and assertive of his set of beliefs and social position: a Muslim and a secular Indian.

His novel Topi Shukla deals with the phenomenon of secularism in this country, especially when it comes to the Hindu-Muslim relationship. It laments the elite and academics whose beliefs don’t match their actions: the farce is secular but the principle communal. It also captures the hypocrisy of teachers in academic institutions.

Such are the people Topi is surrounded with. Finally he commits suicide on account of his deep frustration with the hypocrisy of the academic and political elite.

Topi Shukla, being the epitome of the secular and shared values of this country, becomes the victim. But today numerous Topis in academia succumb to this vicious hypocrisy.

The other relevant phenomenon is communalism, a gnawing parasite which has over a period of time been paved into people’s collective psyche, through sustained social perceptions broadcast against each other’s community. A climate of continuous segregation, polarisation and keeping past memories alive, or manufacturing them, so as to hamper any rapprochement between Muslims and Hindus.

To Rahi, communalism is a disease invented and perpetuated by politicians to burnish their faded sheen. For this small aim they never let people enter the domain of healthy and meaningful relationships, and curtail all the public spaces which symbolise and strengthen communal harmony.

He beautifully describes how, on account of this constant propaganda, both Hindus and Muslims distance themselves from each other. The channel of communication between the two is broken down. Each becomes hostile to the other.

Rahi is mindful with the fact that both have elements of conservatism and resistance to change within themselves. Communal politics has dampened the spirit of symbiotic human relations. His echo in Topi Shukla is profound:

“Hate!

How strange a word it is! Hate! This one word alone is the fruit of the national movement. The price of the corpses of the revolutionaries of Bengal, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh is a single word:

Hate!

Hate!

Doubt!

Fear!”

Rahi was fortunate enough to highlight the hidden communal feelings behind the political correctness of academia, but now interestingly we witness people “coming out” without any “moral hesitation” to announce their communal inclinations and write hate-based mandates for political organisations.

The scourge of communalism has taken a new and more daring shape.

Rahi is not just concerned with the igniters of communal riots and violent mobs, but equally worried about those who believe in shared secular values and are empathisers of communal harmony. He asks critical questions about the future of a country deeply divided on communal lines.

His mesmerising novel Aadha Gaon remains a classic. Set in Gangauli (Rahi's native place) in Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh, it has become one of the primary source narratives for Partition. It demystifies the notion of nationalism while making regional voices strong: the localised preferences of common people, the interaction patterns of Hindus and Muslims and their social behaviour with each other, the breaking and broken Hindu-Muslim relationships.

Well familiar with the consequences of Partition, the novel also offers an alternative to the politics of nationalism, a narrative to respond to and counter this “sacred agenda”. The Muslims of Gangauli do not love the idea of Pakistan. For them, it is nothing but alien to their everyday life – how will it change their life if India gets divided?

They are more concerned about the fate of Gangauli. They are very much worried for the diminishing Indian ethos with the coming of Partition. One is amazed by Rahi’s way of redefining and reaffirming the notions of ghar/ home, mitti/ land or soil, zabaan/ language, khwab/ dreams, etc.

Rahi is not only assertive of his religious identity but equally confident of being an Indian whose roots are massive and giant into this land.

Thus, the question is not limited to Gangauli but seeks its answer from the entire country, the whole world.

Rahi finds a common thread between both communities, bringing in shades of the shared cultural roots, the sharing of public spaces and the common history of living together in everyday life.

He saw the possibility of versatile humanism and Hindu-Muslim harmony in a very different fashion. At a time when the lynching and dehumanising of certain castes and communities is so rampant, and targeted violence has become the new normal, one finds solace and get immense inspiration from such writings.

If the task of communal harmony is handed over to the political elite, it is certainly devastating. It is the people who have to reinvent and reinterpret the past and the relationship they have had with each other. Members of both communities need to start interacting socially and economically, attending shared public spaces, understanding each other’s cultural nuances.

Rahi urges us to recall a historical fact: the social relationship which is made up of a thousand years of history.

But the division of India was the most traumatic experience that India ever had, one of the biggest human displacements in history. Will Hindus and Muslims never write off this “chosen trauma”? Or will they draw a lesson from it and move on, for a social life together?

This is the curriculum that Rahi Masoom Raza has to offer, and this is the pedagogy he puts before us.