Poet of a Shared Paranoia

‘One should look at uncivil people too, so one may know how civil one is’

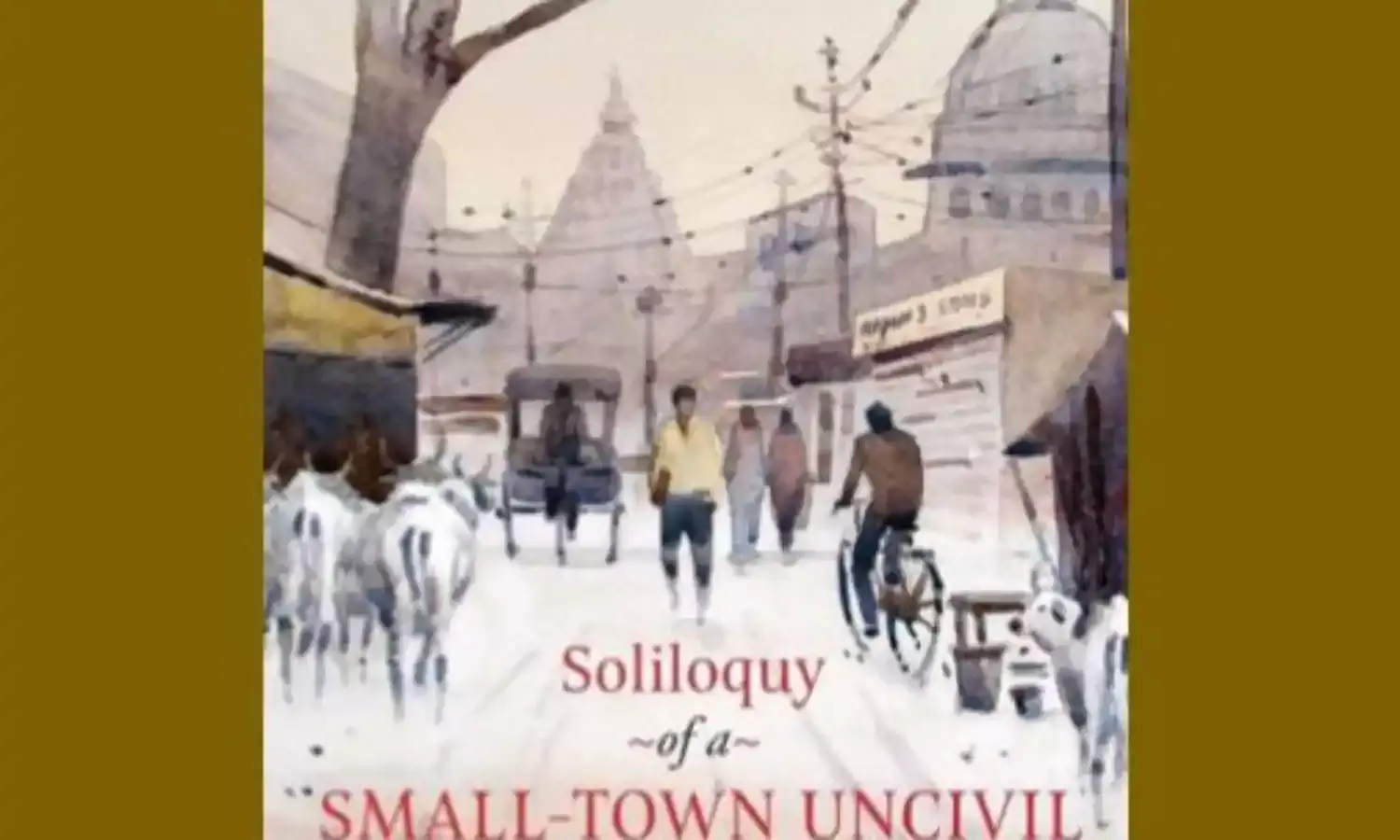

Brazilian poet and critic Régis Bonvicino in conversation with Indian writer and civil servant Kuldeep Kumar Srivastava about his latest book, Soliloquy of a Small-Town Uncivil Servant.

R.B: After three poetry volumes, your fourth book Soliloquy of a Small Town Uncivil Servant came out after almost seven years. A semi-autobiographical book. Your movement towards prose?

K.K.S: The propelling desire has been to tell my stories telling which was too difficult through poetry. When a writer shifts from poetry to prose, his first prose book represents experimentation. Therefore Soliloquy is as much an experiment as it is about my story, my self and those I interacted with or those who interacted with me.

Poetry suffers limitations in terms of telling stories. The US poet Albert Goldbarth while stroking his wife’s arms softly and idly one night, said about poetry, “It wasn’t a flute—but it was the visible blank of a flute, an idea to carry along with me and one day, maybe, make music from.”

Great ideas may fill poems with music, yet poetry constricts narration and thus it has limitations. Perhaps that limits readership. You need intelligent readers with patience to understand poetry.

Prose offers opportunities for better narratives and readers can handle prose writing with much ease. A writer has wider ranging choices with prose. Fast expanding societies need expanded versions of different tales told in plain and not camouflaged prose.

Personally speaking, I felt the need to change the genre.

You devote the first two chapters to your upbringing in a small town, Gorakhpur, where you found ‘every leaf has fallen before’. You talk at length of the miseries small towns possess: suffocating casteism, congestion and hurried sex in families, your university teachers’ behaviour, mafia lords and many more things besides. How did the place impact your writer’s personality?

Soliloquy is an attempt to measure the distance I have travelled from being a child and student: a dependent identity: to the process of its abandonment and moving into an independent adult self.

Your perceptions of a remote past give you moment of prescience. I am not very sure and I entirely blame my ignorance for it, of literary books (not academic books) written in English from eastern Uttar Pradesh where my home town was situated. That is galling indeed.

Persons from small-towns are unfortunately identified with such places and are forced to carry stereotyped persona. It is very sad but fortunately such notions are decaying albeit slowly.

I emphasised the urgent need to draw from Gorakhpur’s vast religious, historical and literary past and factor in elements from its marvellously gargantuan heritage into a holistic development model for the city. The place is already making its way towards a new dawn.

Your books leave one in no doubt that you are much into serious reading. Does in cost you something in terms of sacrifice?

Creativity is not a free-floating thing; not a free-floating art available to each and every individual just like air, water from river and sleep are. None can buy it; it’s not available in any market.

Real creative practitioners develop the habit of taking great care with the tiniest of the things they handle. A tailor who has poorly stitched a shirt gets embarrassed by his sloppiness and never ventures out saying how well the shirt looks. But there is no dearth of writers defending the equivalent of a poorly stitched shirt.

I feel this is where a writer’s reading comes to his rescue. His reading gives his writings worth. Creativity is enervating: it enervates a writer’s brain, his imaginative skills, his intelligence and above all it weighs his mental tolerance.

Remember an artist must accommodate the unmanageable, the malodorous, the unruly and the discordant. And for that he has to be very, very strong. His sacrifices have no values, his pains no meanings. He has to create an endurable milieu for the above.

Of late, the job of a writer is becoming all the more challenging.

Jonah Raskin, who reviewed your book in the New York Journal of Books, felt confused after reading Soliloquy, baffled by a lack of clear identities. Is Soliloquy about you as a civil servant? There is no clarity. Many identities are not clear.

The book is about an anonymous ‘uncivil servant’. The fabric woven inside bureaucracy is inexactly established. Bureaucracy is a large concept and each and every one out there represents a story about him or herself. Even in a hierarchical family order, you have a bureaucratic setup.

Many bureaucrats keep, with no demur, pouring out eulogy upon themselves as civil servants for their exceptional performances, but here is one describing himself as ‘an uncivil servant’.

Identities encompass the behaviour of collective dynamics. You have to decipher the pun in the title of the book. The same reviewer also wrote, the narrator “KK wants to provoke reflection, thought and cerebral interaction.”

Terms like uncivil servant and small-town are examples of shared paranoia.

Don’t Edgar Poe’s words ring in your ears: “In looking back through history, we should pass over the biographies of ‘the good and the great,’ while we search carefully for the records of wretches who died in prison, in Bedlam or upon the gallows”?

At times, one should look at uncivil people too, if one considers them uncivil, so one may know how civil one is.

You rightly pointed out that the first prose book by a poet is an experiment. In any literary experimentation, what issues vie with each other, and what role do a writer’s own personal reminiscences play in literature?

These issues stem from people’s expectations from literature. Readers keep riding out manifestos and arguments sponsoring one school over the other. A reader faces a number of questions that have a bearing on their expectations from a literary piece.

Turning to your question regarding personal reminiscences of a writer, an obvious question seeks answer. Is exploring self by a writer a genuine objective?

I feel writings about self are limited by shrunken imagination, which in my view inhibits the documenting of dynamics of change at a more enhanced plateau.

Today’s literature is in dire need of portrayal of actual images of fast-changing societies, rather than those accrued from accumulated imaginations flourishing on transcendence.

The societies you see are dynamic ones; your own self that you see may not be so dynamic.

Excessive self-intrusion in current literature blurs true literature. Writers must produce a literature which helps in settling societies, at least to some extent. Societies the world over need writers’ ‘tiny help’ in getting settled.

Are modern societies favourably prone to art, culture and literature particularly in this age of internet and techies? Do writers suffer risks nowadays?

If not, how come so much of literature is gushing out? Literature, art and culture act as an intellectual backbone of a society. If this intellectual backbone bends or shivers, it might paralyze and weaken any society in various areas.

It has to be accepted that one of the most enlightening jobs of any writer is to stop human beings from becoming dwarfs. Writers integrate and unify individuals, nations and help the world becoming a whole, big family.

Coming to the issue of risks to a writer, Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz leaves the issue of how much risk a writer should take through his writings to that writer himself. Mahfouz does not want others to justify a writer’s risk. Just like a writer relishes risks his works entail, I do too. Anyway, risks to writers and their writings have coexisted since ages.

What attributes a writer should possess? Are these innate or can these be acquired?

My competence to tackle your question may be questionable. Still I share with you. Observation, insight, intuition, analytical capability and intellectual penetration, so I feel, are a few essential attributes of a writer. He must observe and observe clearly what remains hazy and invisible to others. He must walk through the mist and when he comes out of it, he must combine the other four attributes to pen his experiences.

It’s like Vladimir Nabokov experiments with his insomniac sleeps where on waking up, he tried to restore in his diaries what he saw in his dreams during his troubled sleep. His book Insomniac Dreams every serious writer should read. It teaches the art of retrieval and recording something very unpleasant. It really helps in writing. I mean serious writing.

Serious writing cannot be learnt in a classroom setting. Even innate virtues need be sharpened through vigorous work. Muddling meddlers don’t make good writers. I have my ideals in writers like Nirad Chaudhuri, V.S Naipaul, Hanif Kureishi and Salman Rushdie who divorce elements of ‘self-risks’ before they start writing a book.

Last question. What about your next book? Can you tell something?

I am afraid I can’t except I am at it and it is about very real characters and circumstances that have come my way in my real life. The history of yesterday can be the story of tomorrow. My next book will be an authentic book of tomorrow based on authentic history of yesterday.

Régis Bonvicino is a well-known Brazilian poet and critic with twelve books of poetry to his credit including Sky-Eclipse, Blue Tile and Beyond the Walls.

K.K. Srivastava was born in Gorakhpur and has written three volumes of poetry: Ineluctable Stillness, An Armless Hand Writes and Shadows of the Real. At present he is Additional Deputy Comptroller and Auditor General in the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India.

Soliloquy of a Small-Town Uncivil Servant is published by Rupa Publications, New Delhi, 2019.