The Museum of Broken Tea Cups - Postcards From India’s Margins

Book review

I am in quarantine in my hometown in Mizoram. All passengers from Delhi were taken there from the airport itself. News is almost nil because there is no connectivity in my small room, and I can meet and talk to no one except people who bring my meals to the door.

The news of the arrest of Professor Hany Babu on July 28 by the NIA cut close to the bone because he could have been my teacher. I studied English in Jadavpur University and dreamt of higher studies in Delhi. Babu is an Associate Professor from the Department of English at Delhi University, and a known anti-caste activist. His arrest is another example of the most atrocious campaign against the country’s best minds on the eve of her Independence.

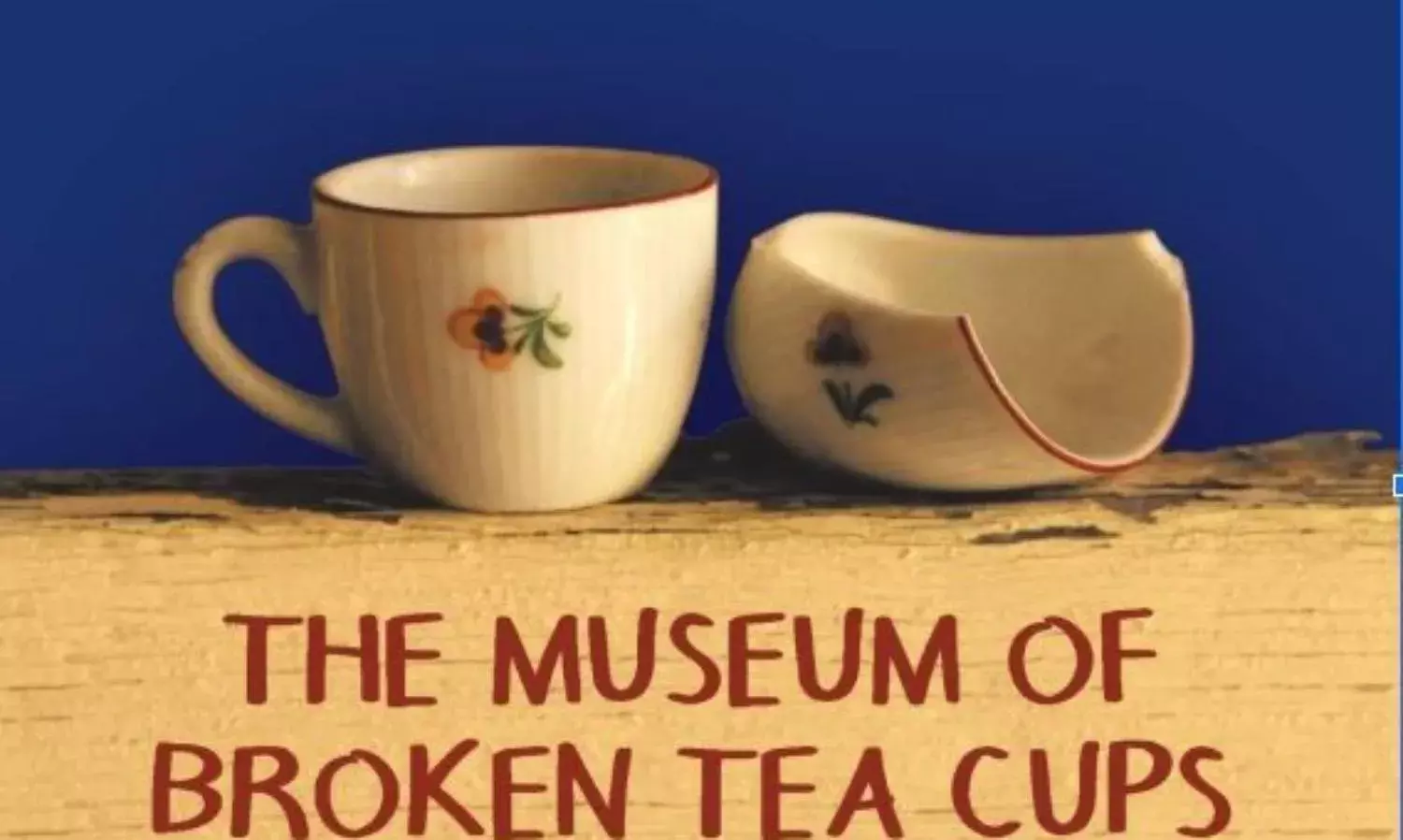

When hope seems at its lowest point, I turn to literature. Dalit literature rises to the mind. Let me tell readers of stories from these most marginalised Communities documented in the recent book ‘The Museum of Broken Tea Cups: Postcards from India’s Margins’ written by Gunjan Veda. Broken.

The cups that were placed outside homes for people whose touch was contamination. The cups that need to break and be lined along walls of a Museum of Horror.

Sage Publications and Dalit Foundation have published this remarkable book containing stories of courage, hope and big dreams from the Dalit Communities. It also documents the communities’ rich contribution in the realms of art and music which remains unsung till today. Author Gunjan Veda tells the stories of these courageous people, the legacy of these ostracised communities so that we can seek, learn and respect.

The (she)heroes in the book, some as young as 12 years old, have seen more pain in their short lives than most people do in an entire lifetime. Yet they soldier on. A 12 year-old girl like Vaishnavi, despite all odds, is committed to studying and hopes to become a teacher one day so that she can teach children of her own community in their own language. How a girl at such a tender age, with commitment and determination, brings about a significant change for herself and her community is an inspiration that will continue to stay with the reader. In the words of the author, “They are people who are determined to make history today; people whom history will acknowledge tomorrow.”

Veda writes that all discourse about Dalits is centred more around the theme of discrimination and less around their contributions. No one talks about their rich legacy and immense knowledge because of the fear lest we begin to respect and value them. Take the example of a postmortem; the great scientific study of the human body to find out what ended the life that flowed within. Who does it? Doctors? Cutting open a dead body is no small feat, yet it is often a Dalit who cuts open and deftly sews it together again. What about the clothes and shoes we wear? Many bunker (weaver) communities are Dalits. Sandals and shoes, including the famous Kolhapuri chappals are their work.

The earthen pots of the Kumbhar (potter) the stone plates, grinders and mortar-pestles are made by the Vadar. Almost all the musical instruments that we see today are a legacy of these communities. The beats of dappu or a naqqara to announce and to entertain have been preserved, nurtured and developed by them. In the 1959 Khwaja Ahmed Abbas made a film Char Dil Char Rahen (1959). Dalit girl, Ahir boy played by Meena Kumari and Raj Kapoor. It was a first in Bollywood when the Govinda the Ahir, ostracised by his village, took his baraat with a single Daf player to his beloved Chawli’s jhonpra. Sixty years later Gunjan has valorised this music in Museum of Broken Tea Cups.

What about dance? Where did classical forms like Bharatanatyam and Odissi originate? Bharatanatyam can be traced to the Sadir dance of the Thevadiyal of Tamil Nadu, Odissi to the sensuous Mahris of Orissa and Mohiniattam to the Tevidicchi of Kerala; all devadasis. And art? Godna artists put to shame many modern tattoo artists. Not to forget the Chitrakathi and Kalamkari painters. The list goes on and the fact remains that these ‘talking points’ for cultural connoisseurs have seldom acknowledged Dalit roots.

Veda writes, “The cobblers who manufactured shoes for everyone were beaten to death if they dared to wear them. The potters who made our household utensils were not allowed to touch them after they entered high caste households. The sculptors who chiselled idols out of stone were denied entry into the very temples that housed those idols. Untouchability was no issue in sexual exploitation. Men and women alike were flogged to death if they attempted to change their profession, or if they drank water from a well, being used by another caste”

How incredibly unjust it is that the very same people, who cleaned the filth from our lives were and are continued to be abused, abhorred and ostracised to the extent that their very name has become synonymous with the word filthy.

Amongst the many remarkable stories being told in this book, the incredible story of Deo Kumar will continue to endure. Deo Kumar from UP, is a man of many talents. He is a writer, director, theatre artist, lyricist, sculptor and above all, a man who has worked ceaselessly for the rights of Dalits for the last 24 years. Instead of getting rattled by the injustice around him for being a Bhangi, Deo devotes his time towards his creativity. Even as he spreads the message of education,

Deo is trying to finish his graduation and has written a book called “Haan, haan, haan, Main Bhangi hoon” (Yes, Yes, Yes, I am a Bhangi). Deo explains to the author, ‘A Bhangi is someone who gives, who suffers for others, who cleans up society’s mess. A Bhangi is therefore noble. Yet, all our life we try to run away from the name. We look at it as an abuse and as soon as we land a job or ‘make it’ in life, we wish to disown this identity. Why?’

In the book, Veda also writes about her visit to the Dalit Shakti Kendra, a vocational skill training centre in Sanand, Gujarat, an initiative of the Dalit Foundation, where she met two young girls, Suraj and Jayashree, who are learning furniture-making and dream of opening a furniture shop in their village one day.

In my work with Muslim women from rural areas of Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, I visited DSK myself on numerous occasions last year where I met and interacted with Martin Macwan, the founder and mentor of DSK. In the words of Martin, “Equality is a non-negotiable value at DSK.” Pradip More is Deputy Director of Dalit Foundation whose own human rights journey with the Dalit Community is inspiring. The centre was established in 1996 when they started a major campaign against manual scavenging. Because of their work, the law came into force. My work in the erstwhile Planning Commission under Syeda Hameed, included special efforts to evolve schemes for the rehabilitation of people dealing in this ‘unclean’ profession.

Bravely standing up to the centuries-old practice of caste discrimination advocating for equality, this is what Museum of Broken Teacups all about; stories of courage to remind us that we are stronger together, and a part of a new community of equals!

It was Abbas who in his film Char Dil Char Rahen dreamt of a new social order, which he predicted will be the New India:

Saathi re bhaai re

Ham aaj neev rakh rahein hai us nizaam ki

Bike na zindagi jahaan kisi ghulaam ki

Lutein na mehanatein pise hue aavaam ki

Na bhar sake tijoriyaan koi haraam ki

Saathi re bhaai re

Brother, Companion

We are laying today the foundation of a system

Where the life of a slave is not for sale

Where the labour of oppressed populace is not plundered

Where criminals cannot fill their coffers.

Ruth Zothanpuii is a Student of literature. Executive Secretary to K A Abbas Memorial Trust. Social worker/working with Muslim Women’s Forum, HID Forum, Dalit Foundation. She has also been Consultant and Secretary to Member Planning Commission where she worked with social sectors from 2006 to 2014.