Lucknow - Of Ganjing and Biryani Without Potatoes

Extract from A Shadow of the Past: A Short Biography of Lucknow

It is the new normal for readers to wake up in Lucknow to headlines like ‘Bullets fly in Hazratganj, whizz past woman’. Hazratganj is a century-old market which the British spruced up in imitation of London’s Oxford Street. It is a place where people go to meet each other. The tradition is for people to dress up in their best and stroll up and down the one-kilometre- long avenue, often with the only purpose of meeting friends. The ritual is called ganjing and those who perform it experience inner joy at the thought that in the midst of friends all can only be well.

But much is not well in Lucknow today. That is why the country’s most populous state is often called ‘ulta pradesh’ or the upside-down province where the population has increased to hundreds of millions of people without employment opportunities keeping pace. Other essentials like infrastructure, healthcare, and literacy are wanting.

Citizens had once exchanged pleasantries in love letters ferried by snow white pigeons. Now messages shared on WhatsApp often make citizens suspicious of each other. There is no room in the city for entertaining the woes of ordinary citizens. There is no room for talk of revolution and rebellion against social injustices either. The main concern of the rich and powerful is to segregate and polarize people. Siddharth Varadarajan is a Delhi-based journalist who grew up in Lucknow in a South Indian family on values based on the Indian Constitution. Today he talks tirelessly against those who want to divide citizens on the basis of religion. He finds this kind of politics ugly and dangerous. It is painful to watch some citizens bullied, mocked, and provoked by others in a city that is traditionally shy of participating in conversations that promote hate.

The present-day attitude is disgraceful and against the ethos of the city. After all, unity amongst its citizens is the backbone of Lucknow’s Ganga-Jamni tehzeeb, the art of coming together like the confluence of two rivers. Trying to turn one citizen against another is no tehzeeb, civilized behaviour, shows no tameez, discretion, and definitely no sign of development. Can the spread of hate ever be an option for a city built on mutual respect and coexistence?

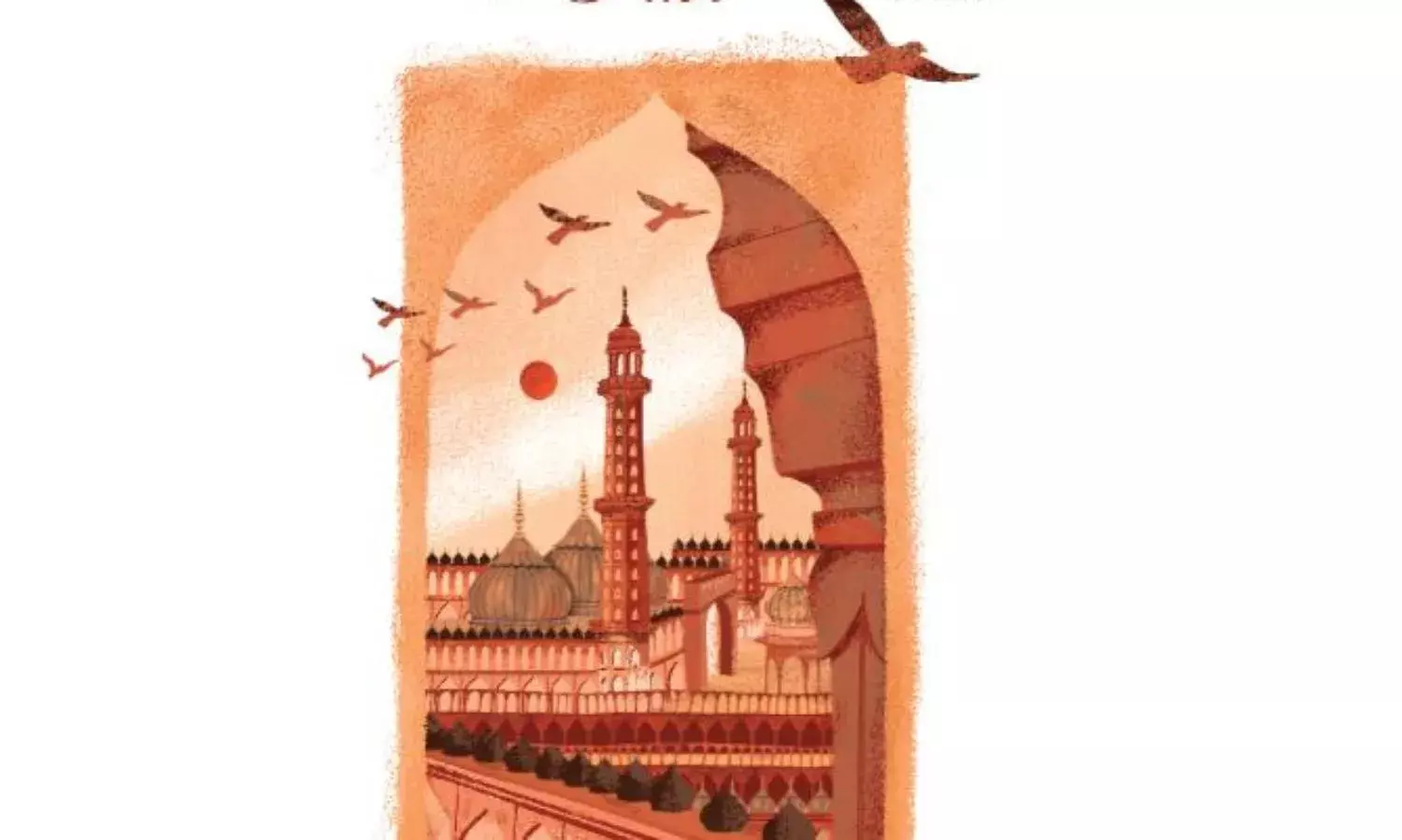

When Lucknow is called a city of culture and refined living, the reference perhaps is to the exalted times that existed between the end of the eighteenth century and the middle of the nineteenth century. Lucknow’s lifestyle has never again been as illustrious as it was during those years until the British annexed the city in 1856. The courteous way of life and prosperity recorded till then has not returned. Instead, life in present-day Lucknow is shabby in comparison. It was only 200 years ago that the region was still flush with funds from landholdings and trade and the constant ebb and flow of human beings from different civilizations had given birth to a very unique Indo-Islamic culture. The nineteenth-century rulers of this land found strength in unity amongst the people they had ruled. They came here as warriors but gave up war to sow seeds of love in the soil. Along with multiple grains of different varieties, citizens enjoyed the rich harvest of living together in harmony.

Wajid Ali Shah, the last ruler of Lucknow, who died in 1887, is the author of about a hundred books. He was a great poet and artiste. His autobiography written in 1849 is titled Ishqnama, the chronicle of love. He designed and built Qaiserbagh, a palace complex and architectural fantasy, as his home. The king conceived Qaiserbagh as an earthly version of a garden in paradise. It was a complex of palaces, courtyards, gardens, pavilions, tombs, and royal bazaars that were later knocked down by the British out of envy and for revenge. According to Ranjit Hoskote, author and cultural theorist, had Wajid Ali Shah been European, he would have been acclaimed as a nineteenth-century artistic visionary. Every year he would open the gates of Qaiserbagh to the public and to invite citizens to participate in a pageant led by him. Irrespective of caste and religion, everyone in the city was invited to dress in saffron robes like a yogi. These events hosted regularly by the ruler helped to dissolve the differences between the ruler and the ruled, and the fear of citizens for one another.

For Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, author of The Last King in India: Wajid Ali Shah, the numerous events regularly held by royalty were important landmarks in getting the diverse population of the city to better appreciate each other. Lucknow gave access to learning not just to the elite; liberal ideas were shared with all citizens. Everyone was encouraged to think philosophically, to take time in composing conversations poetically, and to live in love and peace with each other.

Manzilat Fatima is from the family of the Shia Muslim rulers of Lucknow. Her father is the grandson of Birjis Qadr, son of Wajid Ali Shah and Begum Hazrat Mahal, who led the war of independence against the British in Lucknow in 1857. The war broke out a year after the British dethroned Wajid Ali Shah who left for Kolkata with a large enough entourage to create a mini-Lucknow on the banks of the River Hooghly in a neighbourhood called Matiaburj, the hillock of mud. Here he lived for the next three decades till his death in 1887. In Kolkata, Wajid Ali Shah was first provided accommodation at the British East India Company’s Fort Williams where he complained of too many mosquitos. So he was housed in the quiet suburb of Matiaburj, about four miles away from Kolkata. Once Wajid Ali Shah moved to Matiaburj, his courtly ways, many wives, menagerie, and servants woke up the sleepy suburb and turned it into a lively but close- knit community of people who lived there as if they had never left Lucknow.

Manzilat is in her fifties. Birjis Qadr was poisoned in 1893 at Matiaburj. Since then, this branch of the royal family has not lived in the neighbourhood. A law graduate, Manzilat studied at the Aligarh Muslim University where her father was a reader. Now she lives on Mirza Ghalib Street in Kolkata. A few years ago, a friend who visited Manzilat sighed with satisfaction after eating a meal at Manzilat’s home. She pointed out that what was regular food for Manzilat was special and not easily available. This is heritage food, the friend said to Manzilat. That got her thinking. She gave up law to open Manzilat’s, an eatery in Kolkata where she serves delicious Awadhi food from recipes that have been passed down in the family. Knowing how popular Manzilat’s, her terrace restaurant, is, when

Manzilat came to my place in Lucknow for dinner I made sure to cook the basmati rice biryani with mutton and garnish it with saffron thread. It was an evening most pleasant, except when Manzilat fell silent at not finding any potatoes in the biryani.

Herein lies the difference between Kolkata biryani and Lakhnawi biryani. After Wajid Ali Shah settled down in Matiaburj, his kitchen experimented by roasting whole potatoes and adding them to the traditional Lakhnawi biryani. Today the mutton biryani in Kolkata is unimaginable without potatoes. Meanwhile, Lucknow takes pride in refusing to corrupt the royal biryani by adding the humble potato to it.

A Shadow of the Past: A Short Biography of Lucknow

Mehru Jaffer