Dilip Kumar Shaped India's Modernity, and Lived to See it Reversed

End of an era

The iconic film star Dilip Kumar, who died last week, has rightly been called a symbol of Nehru’s India.

Indeed, the evolution of the Mumbai film industry during his career in the mid-20th century was at one level the story of India’s adoption of modernity.

During his retirement, however, and particularly since the late ’80s, the values more often celebrated in mass entertainment reflect India’s move away from the inclusive and egalitarian values of the decades prior.

Many of the roles played by Dilip Kumar, along with Ashok Kumar and (much more so) Raj Kapoor brought the hero down from the grandeur of proscenium-like spectacle (as in Prithviraj Kapoor’s or Sohrab Modi’s depictions) to the everyday man on the street.

They played characters with whom the audience could identify—even if the hero himself remained on the pedestal of fan following.

Raj Kapoor played even more downmarket characters (in Jagte Raho, for example) than those who had gone before. By the ’60s so did Sanjeev Kumar, and others like Vinod Kumar and Shashi Kapoor. They often represented goodness, honesty, hard work, and compassion.

Meanwhile, heroes such as the evergreen Dev Anand and Shammi Kapoor more often represented fun-loving, slightly risqué, even sexualised, sorts of modernity.

The leading ladies of the mid-20th century represented India’s emergence into modernity even more notably, for to change perceptions of women’s roles was a tougher nut to crack.

At a time when the highest office in the land batted for conservatism, the personas represented by Madhubala and Nargis were pathbreaking for the strength of character and sturdy independence they often represented.

Vijayanthimala and Nutan, and by the ’60s heroines like Asha Parekh and Sharmila Tagore played roles that seamlessly combined boldness with everyday charm, and romance with strength of character. It was a time when the praxis of everyday womanhood changed tremendously across towns and cities across the land.

Already in the ’60s, some top heroines including Mumtaz and Sadhana came to represent a slightly more explicit sexuality and romance, opening the way for heroines like Zeenat Aman and Parveen Babi to break the dichotomy between heroine and vamp—the polarity between good and bad, celebrated and shunned.

A new sort of feminist persona developed on the heels of that boldness, through the sorts of characters that Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi sometimes came to play, even taking up hitherto taboo themes by the ’90s as in Fire.

If modernity essentially turns on individualism, and equality across class, gender and other sociological markers, the exemplars of the film industry in the second half of the 20th century propelled India’s emergence into modernity.

By the last decade or two of the 20th century, however, things were beginning to change—one might even say, regress.

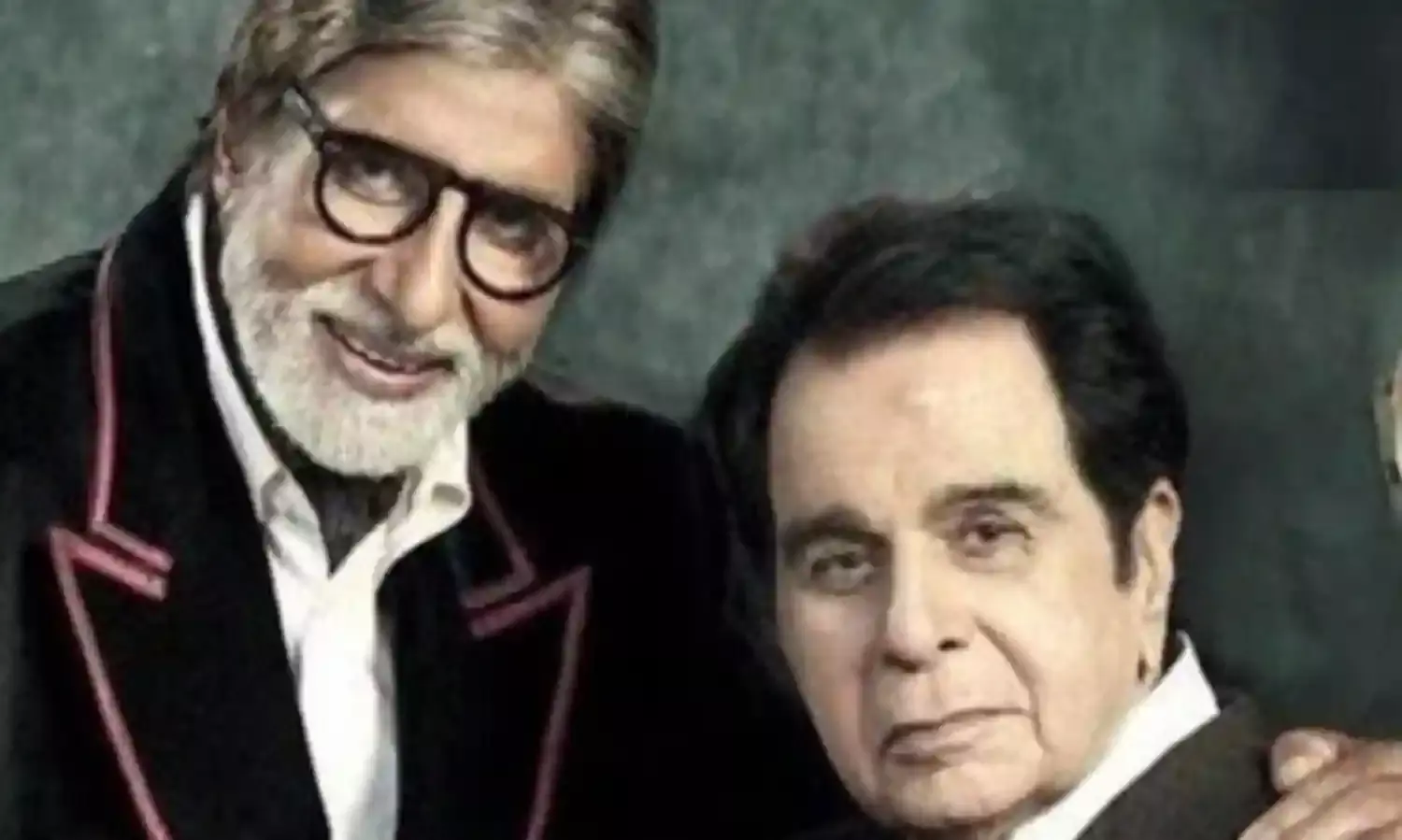

Amitabh Bachchan’s long career is one that spanned a great change, his persona changing from the sort of shy, soft figure he played in Anand to one representing the angst of the emergent urban migrant, frustrated in the search for social mobility.

From the macho, sometimes violent, angst which Bachchan sometimes personified in the ’80s, a muscle-packed Sunny Deol had by the ’90s become the epitome of a heroism that was decidedly macho, often angry, frequently violent.

Television had already overtaken cinema in some respects from the 1980s, and changes in the values depicted and celebrated there were much starker.

Hum Log, which kicked off India’s romance with the tele-serial, was almost a throwback to the values that the films of the ’50s had represented. Of course, its characters were much more intimate, almost like the family next door, not the heroic personas of the heroes and heroines of the big screen.

Things changed rapidly, however. The popularity of Hum Log was soon eclipsed by the religious serials that would bring much of the country to an enraptured halt. Later, saas-bahu type serials would take the plot to conservative social values.

In the current century, tele-serials have often portrayed gender, class, and social stereotypes which revive tropes that cinema had gradually undermined and replaced over the past century.

As if in tandem, some of the biggest Bollywood hits of the ’90s too celebrated the high life of the rich and famous. Family values too—including a fair dollop of patriarchy.

Whereas the Mumbai film industry played a huge role in integrating India in the third quarter of the 20th century, imbuing it seamlessly with what might loosely be called modernity, television as well as the music videos industry took over the role of shaping society to a large extent since the ’90s.

Music videos often portrayed crass, hyper, multicoloured visions of an unreal virtual reality that could often be described as obscene and dehumanising, particularly with regard to women and certain other types of citizens.

Reality shows too have tended to do this in recent years, often caricaturing certain genders and social roles.

Those who cherish India’s imperceptible slide into modernity through the celluloid personas of a Dilip Kumar, a Sanjeev Kumar, and a Smita Patil back then may well feel doubly regretful, mourning an era along with a titan.

Cover Photograph YouTube