Freedom Stories: Hear the 'Denotified Tribes' Speak for Themselves

Illustrating the fabric of DNT life in India today

When the marginalised who have been kept voiceless for several decades can be heard speaking for themselves what is expected is an extremely powerful narrative coming straight from the heart.

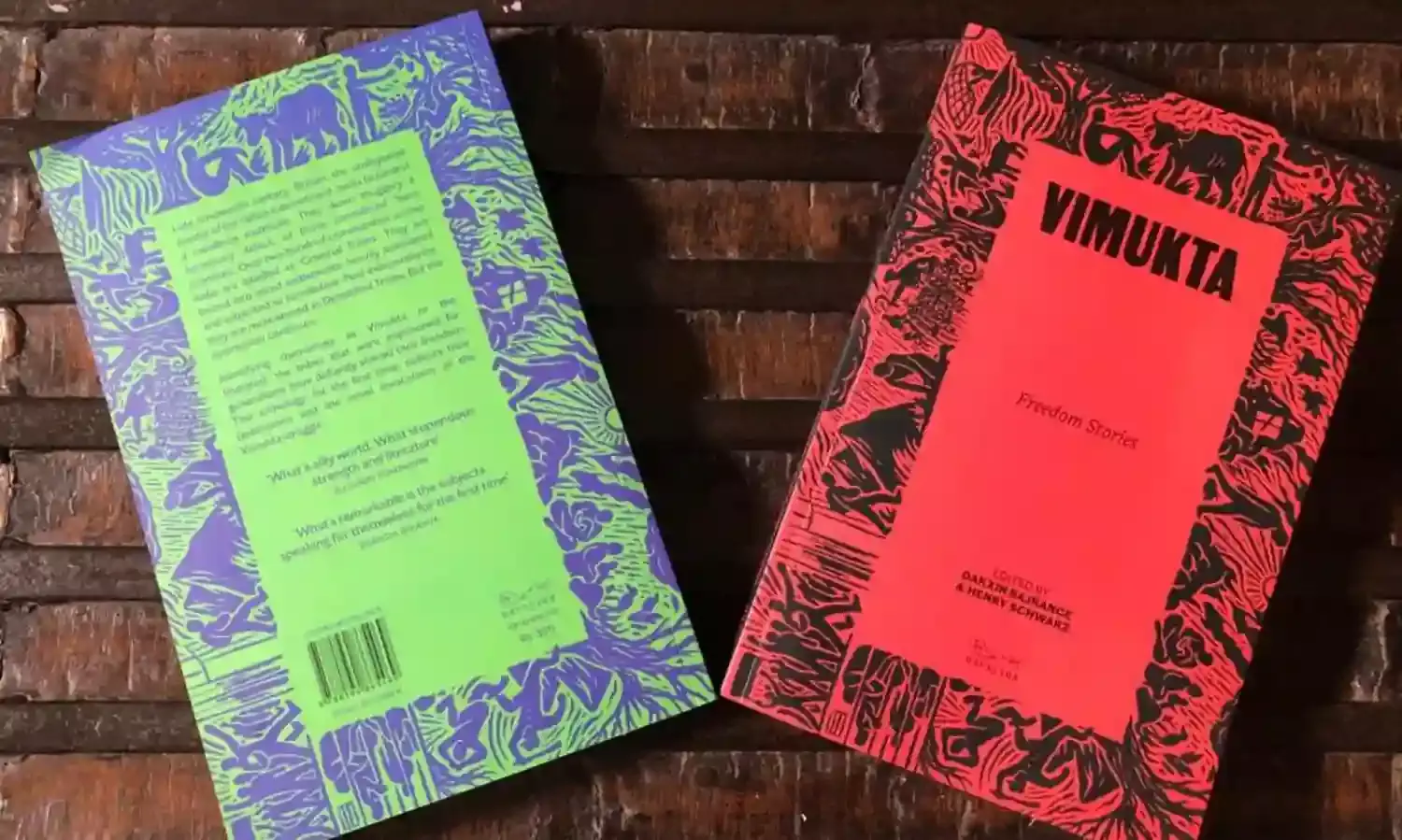

This is exactly the case with the landmark anthology Vimukta: Freedom Stories which expresses narratives of people from the Denotified Tribes (DNTs) who nearly seven decades after no longer being identified as “criminal tribes” continue to be kept at the lowest rungs of the social ladder in India.

The volume will be released on August 31, which the Vimukt or liberated tribes celebrate August 31 as their Freedom Day as it was on this day in 1952 that they were freed of the tag of being criminal tribes.

Though the criminal tag was removed, the stigma persists, ensuring that people from these communities continue to be pushed to the margins. Only in the last 20 years has there been a movement to get them their due rights.

The volume is edited by Professor Henry Schwarz who has been associated with Georgetown University, and Dakxin Bajrange who is a prominent cultural activist and filmmaker from the Chhara denotified tribe in Ahmedabad.

“Professor Schwarz has been working with the DNTs since 1999 at the behest of eminent writer the late Mahashweta Devi who was the voice of the marginalised people in India,” Bajrange told this reporter.

He said the edited volume “is a creative expression of people of those communities that are still struggling for an identity despite being performers for several decades. Though we have been expressing their voice through theatre and films, this is a landmark effort coming from the DNTs.”

Schwarz and Bajrange point out in the book that “The eight texts collected here are far from comprehensive, but rather form a snapshot of the experience of being branded a criminal in independent India.

“These voices, from different regions, languages and cultures of the subcontinent, speak to the existential reality of living under the colonial hangover of alleged criminality. Despite their differences, each highlights the experience of crime and its enormous shaping role in defining identity and the possibilities of living today.”

Freedom Stories’ most original contribution is to allow us to hear the voices of these oppressed populations who have been subjected to a century and a half of systematic oppression.

“Allegedly ‘born criminals’ speak in these pages, telling their first-hand stories for the first time. Reacting against an historical legacy of oppression, these contemporary storytellers bear witness to the historical experience of their ancestors, and point us towards an uncertain but hopeful future,” the editors underline.

The stories “come from all regions of the Indian subcontinent, with translations from Marathi, Hindi, Gujarati, Telugu, Bantu and Narsi-Parsi (thieves’ argot), illustrating the fabric of DNT life in India today.”

‘De-notified’ as criminals by Prime Minister Nehru on 31 August 1952, the former criminal tribes were quickly re-criminalised under a series of habitual offender statutes in various states.

“Rebranded as De-notified and Nomadic Tribes (or Vimukta Jatis in Hindi, DNTs in English), this legislative Frankenstein’s monster has nowhere found a home under India’s constitutional provisions,” the editors write.

“For the last twenty years we have seen flicker into life a nascent movement for the civil rights of these wrongly accused, who, like convicted felons the world over, have few rights to housing, education, health care, or representative democracy.

“The government of independent India has attempted some small measure of redress, first in its decriminalization of the tribes, and then its appointment of various committees of enquiry to study the issue and to propose recommendations, as it has done since independence.”

“The movement to secure civil rights for the DNTs over the last fifteen years,” they state, “has been successful in achieving the appointment of a national commission within the ministry of social justice and empowerment. Yet this commission has accomplished precisely nothing, and its leadership has been staffed by political appointees with a vested interest in accomplishing less than nothing.

“The spearhead of the movement has not been constitutional reform but popular activism, with various groups taking to cultural production and public performance to voice their grievances and build awareness among the general population.”

To substantiate their viewpoint, the editors elaborate on the colony of Chharanagar in Ahmedabad, the free colony into which inmates of the Ahmedabad Settlement, administered by the Salvation Army from 1930 were released.

They observe that Chharanagar today is a thug’s paradise, where roughly 50% of the resident families brew country liquor under the eye of the police. Many of the other families are engaged in games of chance, such as numbers, dice and cards. Insurance deception schemes engage many, as does prostitution, bootlegging, and smuggling.

“Among the most lucrative schemes is the filing of false charges by the police against suspected criminals, or ‘persons of questionable character’, who must answer charges against them based on secret evidence.

“The existence of such emergency legislation, such as the Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Act (or PASA) affords police the authority to continually intimidate suspects into paying bribes to avoid prosecution and jail time. Many default to incarceration when the bribe is exorbitant,” the book explains.

“Strikingly, Chharanagar boasts an enormous density of legal professionals, many of whom are employed in defending community members against false cases. Such cases can drag on for years in India’s sclerotic legal system, and the combined pressure of police extortion and legal limbo drives many to bankruptcy. In the long run it is easier to pay the bribe.”

On the role of the police it explains, “Stigmatized populations are sensitive to pressure, and research has shown that police are a large motivator for the commission of crime, turning a blind eye for a bribe, or actively encouraging, inciting or compelling illegal activity in order to profit.

“The threat of coercion convinces ‘born criminals’ to follow illegal pursuits under threat of a beating or the lock-up. Police take a large cut of the profits from illegal activity either as protection money or as direct beneficiaries of fenced goods, and so crime is systematic and normalized, to mutual benefit.

“Communities that have been criminalized historically learn new methods of existence over time. If they had not been traditional brewers of liquor, they become so under changing needs and circumstances, such as confinement in settlements or housed in states under prohibition, such as Gujarat. Their experience in transporting goods became useful in making objects appear or disappear.”

The volume goes on to say how these settlements were centre of innovation of unique technical skills when the old ways were suddenly shut off. Former nomads now catered to the needs of the sedentary, especially as they fell out of line with traditional norms of settled life.

“The free colonies to a certain extent became havens for free expression: as in many gypsy communities the world over, outsiders come into the ghetto at night to experience its exoticism and relaxed morality. They leave before dawn having had their fill, perhaps paying a police bribe, and returning to their respectable families, no questions asked. If there was trouble, police would round up the usual suspects.”

Bajrange told The Citizen, “In these times when the country is going through a difficult phase, the voiceless have tried to speak out. Even as the country celebrates its 74th Independence Day, many of them are still very far from a term called ‘Azaadi’. They do not understand what it means and translates into. They continue to be denied their democratic rights as nobody is bothered about them.”