Memories of Afghans Come Rushing Back

The sound of Pashto always enticed everyone in that small office

The return of the Taliban brings back haunting memories of their previous regime, and of the activities of the Mujahideen during the tenure of President Mohammad Najibullah.

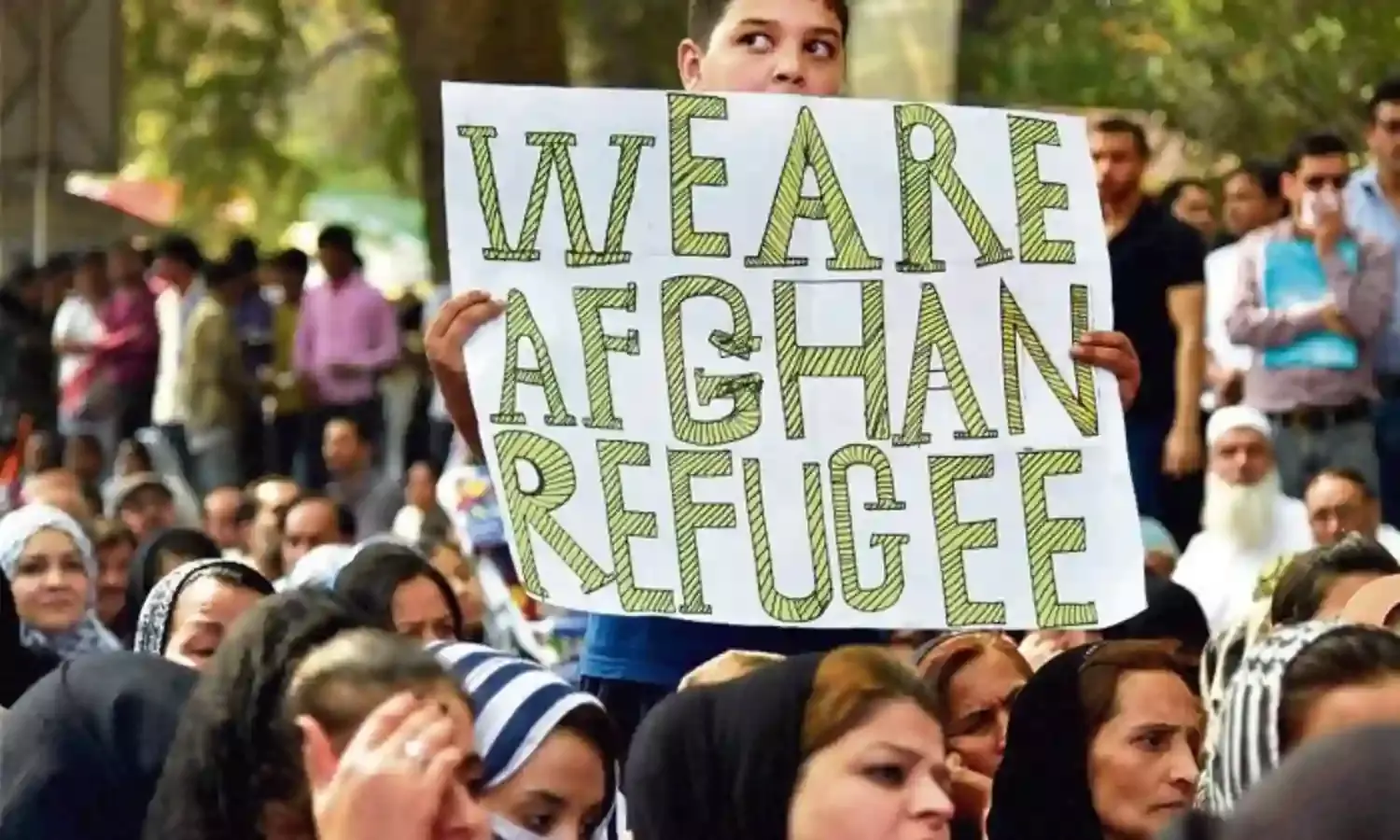

A large number of people in north India have had interactions with Afghans at one time or another. As Afghanistan once again makes headlines around the globe it is the plight of the people living there, particularly women and children, that is of concern to every sane human being.

The same is the case with this writer, who has quite often had a brush with events in and around Afghanistan in both personal and professional life as a journalist. All these memories have come back compelling one to jot them down.

Talking about the personal experiences, I grew up in Solan, a small town in Himachal Pradesh where Afghans were always welcomed, particularly in winters, as they went around selling dry fruits and also working as daily wage labourers doing jobs that required immense physical strength. Dressed in their Pathani suits that consisted of shirts and baggy pyjamas with huge pockets, it was a delight to hear them talk in Hindi laced with a Pashto accent.

This was the era of the early 1980s with Najibullah in power, and a phase of progressiveness back in their country where women were fast becoming equal participants in society. But as the Mujahideen militant activity increased against the Najibullah government, the visits by these Afghans became less frequent.

Then during my stint as a reporter in Patiala I had become friends with Ravinder Salaria, who worked with the marketing department of the paper I worked for. As the friendship grew I came to know that his family had stayed in Kabul for some years. He could speak a bit of Pashto which always enticed everyone in that small office.

He would narrate the experience of the Mujahideen rocket attack on the Indian embassy and the rest of us would listen to him in pin drop silence. “We kids studying in the Kendriya Vidyalaya run by the Indian Embassy were really excited and scared at the same time,” he would say, adding a dash of Pashto to the narration.

As the bond of friendship grew, I came to know about the trauma his family had undergone. He related that his father Chain Singh Salaria, a hockey coach, had been sent to Kabul to train the Afghan hockey team. He had accompanied the Afghan team to the USSR to play some friendly matches. As the 16-member team was returning to Afghanistan and had just crossed over into the country’s geographical limits, they were abducted.

Even when I left Patiala in 1998, the family was still awaiting news of the fate of the hockey coach. Ravinder’s mother Kanchan Salaria was later employed with the Netaji Subhas National Institute of Sports in Patiala and probably retired from there. I lost touch with the family in 1998 when I was transferred to Gujarat. All I know is that they are now living in Pathankot. Ravinder’s sister had gone on to work for the Russian airline Aeroflot.

I always wondered how the family was coping with the uncertainty and endless wait for the return of their patriarch. Being a frequent visitor to their house and treated with love and affection there, I never could gather the courage at that time to file a story on them. Even today I am writing this in a dilemma as I have had no interaction with Ravinder for more than two decades. Perhaps maturity coming with age has given the strength to jot it down.

All that the family had wanted was the Government of India to find out the truth about him, along with the sequence of events as to what exactly had happened and who had kidnapped the team.

Thereafter came the infamous Kandahar hijacking, and along with other reporters I was involved in covering the demonstrations by family members of the passengers on the Indian Airlines flight 814 that was coming from Kathmandu to New Delhi. It was taken to Kandahar after halts at Amritsar, Lahore and Dubai.

The passengers’ release was secured by the Indian government after the release of three terrorists including Maulana Masood Azhar who later founded the terror outfit Jaish-e-Mohammad, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh who was reportedly involved in the assassination of American journalist Daniel Pearl, and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar who has reportedly trained militants in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir.

It was during these events that a former Punjab Director-General of Police candidly told this reporter that the plane should not have been allowed to leave India and there were a hundred and one ways of doing so. His views were acknowledged by many later.

How fanaticism breeds was there for everyone to see when the Taliban went on to destroy the monumental statues of Buddha in 2001 in the Bamiyan valley of central Afghanistan.

I was horrified when I saw the Bamiyan Buddha demolition being equated with the Babri Mosque demolition by Hindutva fanatics on December 6, 1992 during an Eid-ul-Adha sermon. In the world of fanatics, whatever faith they claim to subscribe to, two wrongs make a right and this continues to be witnessed across India today as well.

Once again I had a brush with Afghanistan when during a stint in Uttarakhand in 2008 there was a story to be done on an Afghan woman who had got the police in Pithoragarh to book a serving Indian Army officer on charges of bigamy.

The complainant, Sabra, who could speak fluent Hindustani related that the officer had married her during his deputation in Afghanistan without conveying that he was already married and had two children in India.

She said that she had met him while working as an interpreter for the International Red Cross. He had allegedly converted to Islam to marry her in 2006 and had returned to India after his assignment leaving her behind. She had tracked him to Pithoragarh where he was posted at the time.

When asked how she could speak such fluent Hindi, Sabra, then 20 years old said, “I have been educated in Pakistan.” The fate of the case is unknown as I soon changed my job.