‘We Will Not Be Forgotten. We Will Not Let That Happen’

‘Afghanistan’s history is repeating itself and we need to learn from it’

“I wish that instead of me.. you could have a famous, successful female artist from Afghanistan right now with you. Unfortunately the situation there is not giving us this option,” says Parween Pazhwak, an Afghan poet and artist who lives now in Ontario, Canada.

“I have lost contact with my artist friends inside of Afghanistan in the past one week. The reasons are obvious: they might be out of electricity, no access to internet, out of mobile credit, or they may not have money: as we know the banks are closed.

“Plus they simply might be afraid to be in touch with any outsider. They might be hiding in their homes or have already fled from it. Finally, they might be stacked at the airport right now, or not even be in Afghanistan any more. Anything is possible right now.”

Pazhwak, who has composed more than 20 books in Farsi Dari and Pashto, many of them for children, describes her journey as an artist in Afghanistan.

“Fortunately at home there was paper and colours always available around me. My beloved father and my older sister were naturally good and drawing and painting.”

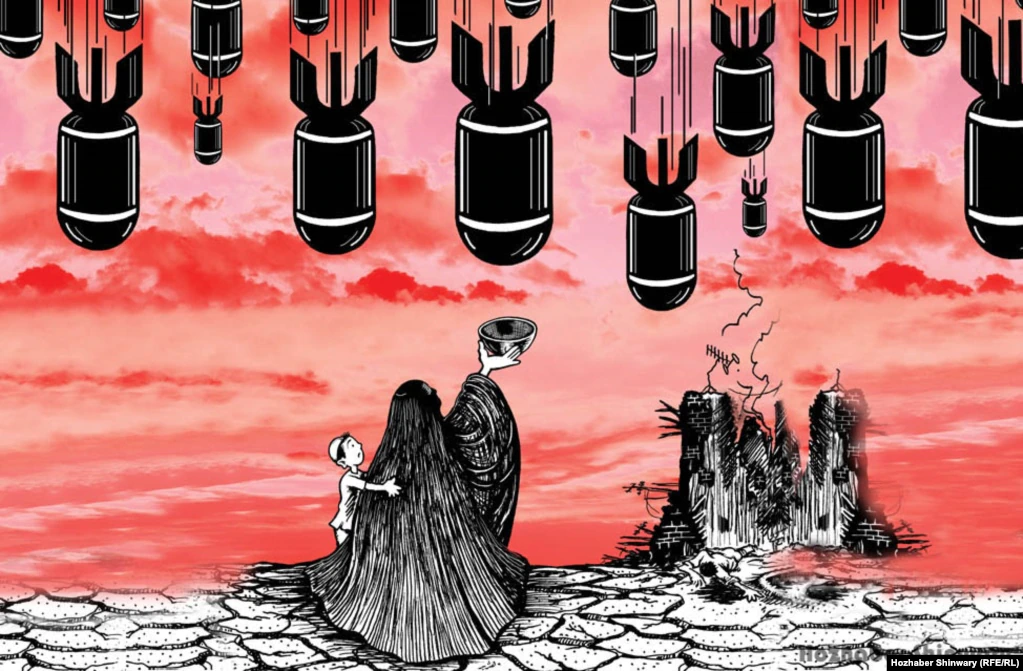

While a student at the Abu Ali Sina Balkhi medical institute in Kabul, Pazhwak had the chance to help renowned Afghan cartoonist Hozhayeb Shinwary make the country’s first animation films, in Kabul.

“It was very long ago, in the 1980s, but this is my most well known achievement in art,” she smiles.

“During the Communist government of Afghanistan from 1978 to 1992, artists were free to create art, but not any art that would reflect the tragic invasion of the Soviet Union’s Red Army, or the crimes committed by their puppets in government.

“During the time of the Islamic government of the Mujahideen, 1992-96, and after that during Taliban rule, 1996-2001, artists were forbidden to create any new art, or respect the old. We all know the heartbreaking fate of the Bamiyan statues.”

It was when she was out of the country, says Pazhwak, “in the past 20 years of the rebuilding of Afghanistan during the Islamic Republic government”, that the younger generation of artists were represented.

“Freedom of expression and a lot of popular media channels made a promising land for art to grow. Although the ongoing war with the poor economy were heavy obstacles, especially for artists in the provinces.”

But “there was still hope, overall there was hope, and opportunities. That was until last week.”

“If I stayed in Afghanistan I don’t think I would have been alive,” says Nadia Ghulam. “Even if the Taliban would not have killed me I would have committed suicide.”

In 1993 when she was seven years old Ghulam’s house was bombed. She spent the next few years going from one hospital to another, and by the time of her recovery in 1996 the Taliban regime had taken control of Afghanistan.

Women were forbidden to go to work or leave the house unaccompanied by a male. To support herself and her family, Ghulam had no choice but to pretend to be a man. She disguised herself as her dead brother for the next ten years to earn a living.

“I thought one day the rules will change and women will be allowed to work and I will be Nadia again.. But the hope for tomorrow lasted for ten years.”

Afterwards she was able to move to Barcelona, Spain for proper medical treatment with the help of relief NGOs. Having moved to Spain she wanted to show the world the situation of Afghanistan beyond the Taliban. So she wrote the book The Secret of My Turban, a story told through the eyes of a young girl.

Ghulam says she lost her childhood to war. Now, at 36 when she sees young girls living their lives, she feels she did not have anything like them. “I grew up in a country where there was constant war. My mother would ask me to pray for peace, but I did not know what was peace.”

With the recent upheaval in Afghanistan she feels helpless, and is constantly watching the news on television for information about her family’s safety. “I haven’t slept for days,” she shares.

With the Taliban government maintaining that women will be “allowed” to work and will be free, Ghulam thinks “it will be very difficult for women to go back to normalcy again.”

“I have been out for a couple of years now,” says actor and activist Leena Alam. “After the series and after some of the films it was a bit.. even at that time it was threatening.. so I left. I left.”

Alam’s family moved to the United States in 1989 after the Soviets withdrew and the Mujahideen came to power. Afterward she often returned to her country.

“I had gone to Afghanistan during the Taliban regime as well, but during that time of course cinema was banned. Then every year after they left I would go, and in 2007 I went and I stayed.”

Of her work as a cinema professional, “2007 was when I started taking it seriously, knowing that actresses were needed in Afghanistan. I stayed more than a decade and tried to work and do whatever I could through acting, through cinema.”

“Things got worse day by day, for all people but especially for the filmmakers, because we could have bombings during our shoots but we still continued, we continued.

“So for the past 20 years filmmakers tried their best even though security was not good at all, even though there was lack of funding and people used their own money to make films. Everybody tried their best.

“But now everything is gone. The 20 years of hard work, for everybody, and every aspect, it’s all over now.”

In the decade that Alam worked in her country under the US Islamic Republic government, she can’t remember any film or series she worked on when there were no bombings.

“In 2007 when we were doing Kabuli Kid, the film we were shooting by Barmak Akram, there were three bombings in that one month we were doing shootings. Three bombings. Our car would pass while they were sweeping the blood off of the roads, and we would pass and see the blood being washed off from the floor.”

Threats forced Alam to leave in 2017. Asked about the Taliban’s return to power she tells The Citizen:

“They are against art. They are against freedom of speech, freedom of expression. They are the enemy of art. Right now they have only allowed broadcasts of news. All the TV is under the control of Taliban and they have only allowed news. All the entertainment programs are banned.”

She thinks it is all the more important now for the people of Afghanistan to have entertainment, and art, because

“It speaks the truth. Through art. One way to speak the truth, to speak your mind, to speak against brutality, about everything - is through cinema, through writing, though art. So it’s very important. It’s a way that you bring out the truth and make the culture of a country, through the art. You cannot kill the art, because it’s part of the culture, in a country and in a society.”

Another Afghan artist now living abroad, Malina Suliman started making art professionally in 2010.

“There is not any answer why I want to make art, because art is something I see as running in my blood,” she tells The Citizen.

“When I was a kid I already saw myself making drawings, and already felt that I am an artist and I want to learn more. So as I grow, art is also growing in me.. I don’t know how what it will be in the future because it grows with me always.”

Known especially for her street art, Suliman found that with the growing audience for her work in the 2010s, in which she “expressed the voice of the women and the youth” came increasing threats and suspicion.

“I not only made street art but also I did a lot of exhibitions. In Kabul, Kandahar, Mazar, Helmand. And when I did the exhibitions in Kandahar City, almost all the time, a lot of visitors came and it was always men.

“I do appreciate even in that time that men really wanted to come and see the artwork. But what I miss was a single woman. Standing or presenting the work, or being there, was just only me. And I have to cover my face, just show my two eyes, and then I can present my work in Kandahar City.

“So I am happy that I had this opportunity. But I thought okay, for whom am I producing my art works? Is it my art work is just for the male, or is it also the female is included? Because most of my artwork was also for the voice of the woman.”

Suliman says this paradox was one of the reasons she started working on street art.

“Because the street, the walls itself, it’s like a performance every day. So I started to make street art so that females, or also those people who are not joining - maybe the Taliban, maybe any different kind of public - they can visit my work. If they want to or not.”

With her provocative works critical of Afghan politics and culture, says Suliman, for a few years she achieved a bigger audience, “which was very nice. But there was also a part which was more negative: that I also reached to the Taliban.”

“And they thought that okay, this is one girl, and she is out on the walls asking for her rights, or standing for, expressing what she wants. But this can be multiple, and can get more and more. Because they saw that there were more females also getting interested. So the first thing they wanted: to stop me.”

This led first to threat letters sent to her home, and later on, “when I didn’t want to stop, the time arrived when they attacked my family.”

She moved with her family to India. After some months in Mumbai she secured a scholarship that led her to the Netherlands and later to Canada where she now resides.

All her family are back in Afghanistan, she says, where they are staying together to keep an eye out for each other. “I don’t know about their future, if they are safe or not.”

“Everyone in Afghanistan at this time is looking out for their life, they are in survival mode. It is very hard for someone to stand up for themselves.”

As for the international community, “They have left us to burn, and also made them fire themselves. What about Americans, who gave hope and then suddenly took everything

away from Afghanistan?”

Suliman adds that with the Taliban controlling media coverage within Afghanistan, coverage by other channels is all the more important.

She says the media represent Afghan women stereotypically. “The media always keeps me under the title of Afghan, Muslim, artist and woman. What they don’t represent is just an Afghan artist.”

Meanwhile now the Taliban itself is performing for the media, by saying one thing and doing something totally different.

“The media is showing the false promises of the Taliban, but the ground reality is very different.”

Some reports have trickled out in the wake of the “messy” US pullout, in Biden’s words, from Afghanistan.

Last month the Taliban told the media they had killed comedian Fazal Mohammad, popularly known as Khasha Zwan, who was also reportedly a policeman in Kandahar.

“He was not a comedian, he fought against us in several battles. He had tried to flee when we detained him, prompting our gunmen to kill him,” said spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid.

Asked whether the Taliban would allow artists to continue with their work, Mujahid reportedly said that singers and filmmakers would have to switch their profession “if assessed against the Shariah”.

While the group has claimed that the media will be free, days after taking control it raided various media offices including that of Afghanistan’s leading news channel, TOLO News. There are reports of journalists fleeing the country to save their lives.

Besides the murder and reported torture of Reuters chief photographer Danish Siddiqui, TOLO News journalist Ziar Yaad Khan was recently assaulted by the Taliban.

“I was beaten by the Taliban in Kabul’s New City while reporting. Cameras, technical equipment and my personal mobile phone have also been hijacked. Some people have spread the news of my death which is false. The Taliban got out of an armoured Land Cruiser and hit me at gunpoint,” Khan tweeted.

German channel Deutsche Welle said the Taliban shot and killed a relative of one of their journalists while conducting a house-to-house search for the reporter.

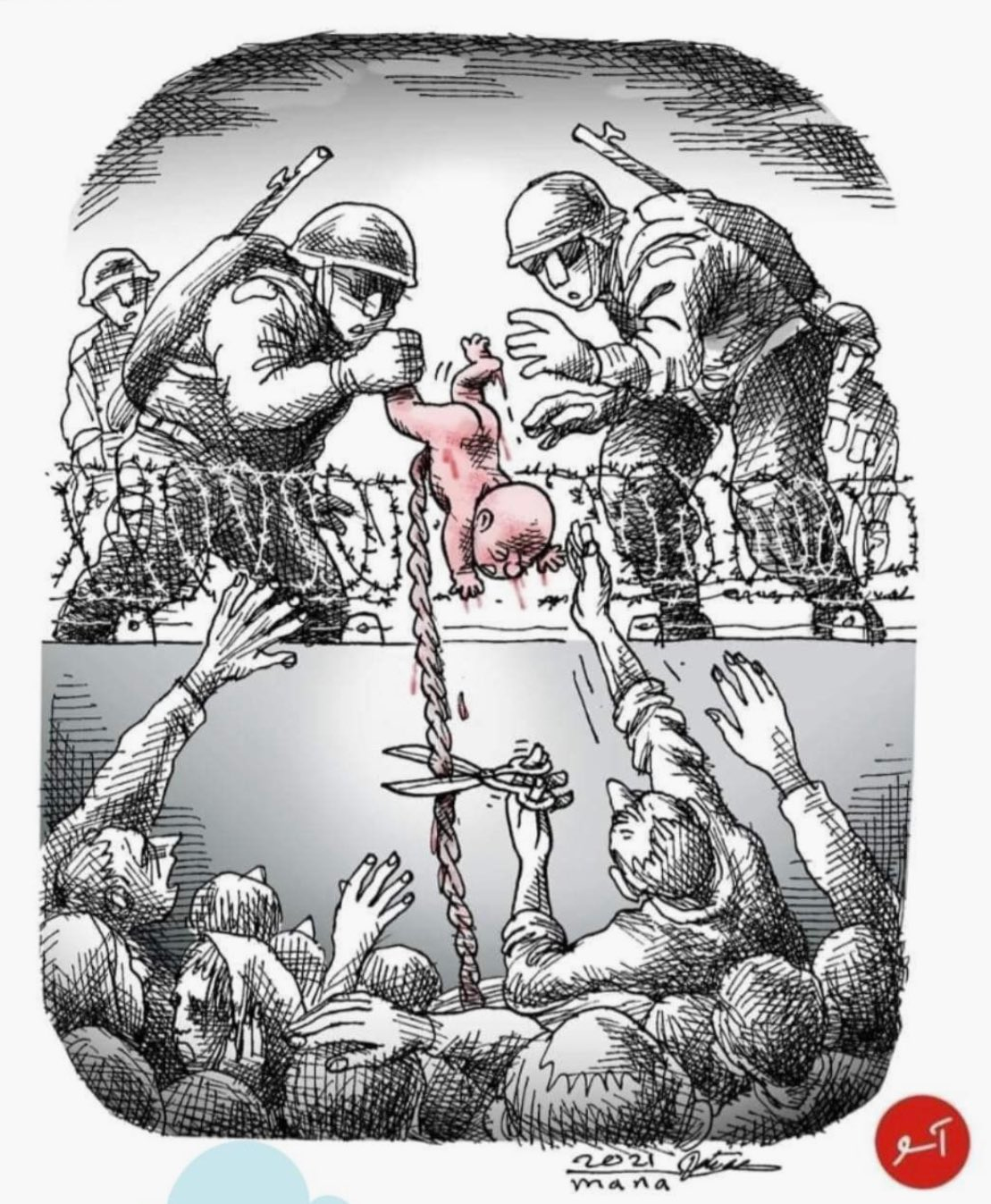

As the upheaval continues, most Afghans who decide to leave their country are likely do so on foot to Pakistan and Iran. Other countries that have committed to welcoming Afghans (temporarily, in small numbers) include Albania, Qatar, Costa Rica, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, Colombia and Uganda.

“In this moment of dire and violent transition, it is impossible for us to comment on what the future looks like. We are praying for an end to the violence,” said Sunita Viswanath, co-founder of the NGO Women for Afghan Women.

“My message to the international community is that in this hour, the world must stand with the people of Afghanistan. Nations must open their borders and welcome Afghan refugees who are fleeing for their lives.”

Through a recent series of drawings titled ‘Forget me not’, Parween Pazhwak wants to remind people that what is happening under the Taliban regime right now has happened before in Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan’s history is repeating itself and we need to learn from it,” Pazhwak tells The Citizen.

“Now, with the return of the Taliban, it is too soon to talk about the future of art. It is not just art but is the destiny of our nations facing a big question mark. Our constitutional law, our freedom of belief, our freedom of speech, our freedom of homeland, they are all hanging in the air.

“Still we should not forget that earlier Afghanistan has a rich history of art, culture.. and since we are going back to innocent times: our roots are deep enough to not burn or freeze by the hot and cold blows of war and fundamentalism.”

“My message as a representative of artists that are not able to talk right now is: don’t let go of Afghanistan, don’t give up on Afghanistan, stay with Afghanistan.”

“Personally I am an optimistic artist, I have always believed in art and in humanity.. If the people of the world, the media, the global powers do not forget us, we will not be forgotten. And we will not let that happen.”