Mongoose Turned to Paintbrush Bristles in Howrah Villages

While NGOs work to build wildlife awareness

KOLKATA: With human activity having decimated wildlife populations by an average of 70% since the 1970s, conflict between humans and other animals continues to surface amidst widespread destruction of habitats. Behind the scenes, efforts are underway to mitigate the conflict.

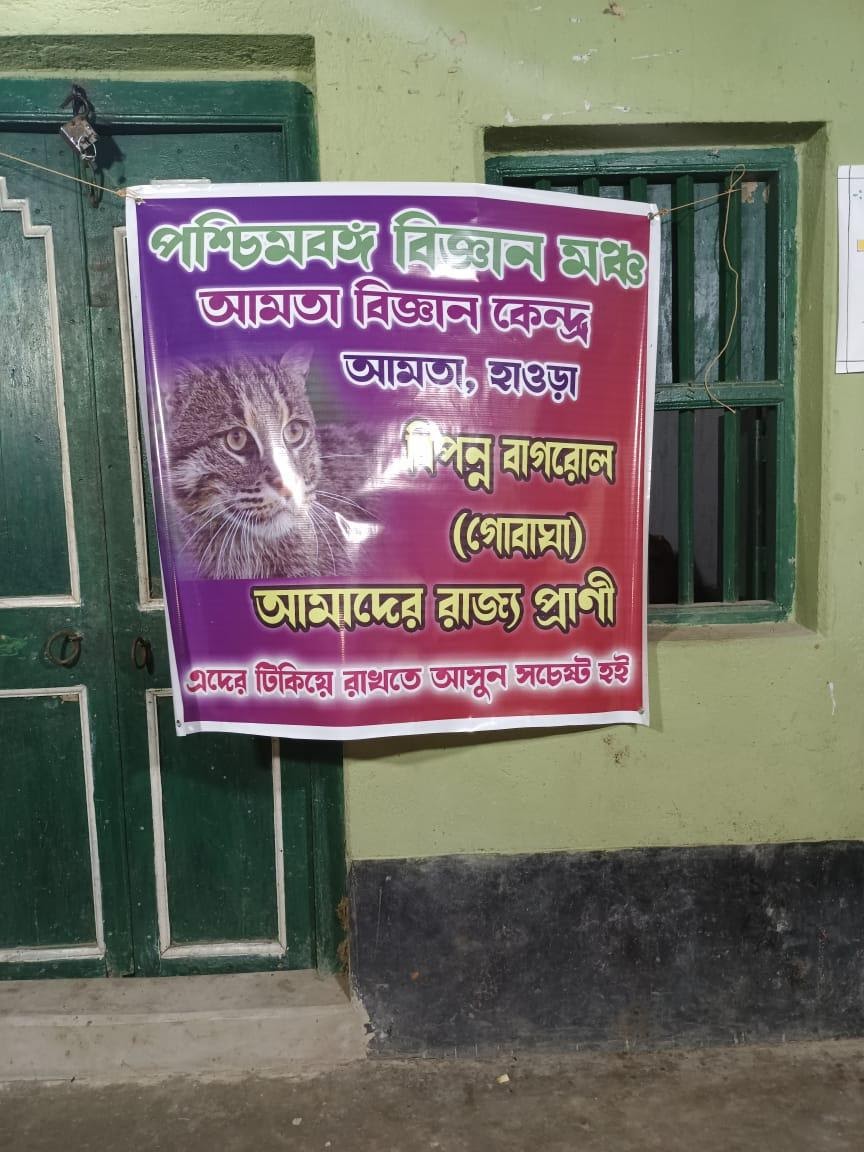

The fishing cat, the state animal of West Bengal, often frequents peanut plantations in Amta, a village locality in Howrah. Here resident volunteers, many of them still students, have teamed up with the Forest Department to conduct awareness programs to protect the animal from our species.

Subhradip Ghosh, a volunteer for the Howrah Jela Jautha Paribesh Mancha, the NGO that runs these Human Wildlife Conflict awareness programs, says the solution is to teach people how to deal with animals who wander into village residential areas.

“As the lowlands in Howrah are slowly depleting, the fishing cats are losing their habitats, and are being forced to wander into the residential areas,” says Ghosh. “Not only that, but poachers also regularly come to this area to illegally hunt. They come in big groups of 300 to 400 people seven to eight times a year.”

Besides the fishing cat, mongoose are also endangered in the area as poachers hunt them for their fur, for use as paint brush bristles.

“It is an inhuman act to destroy the life of an animal for your art… We once confiscated 15,000 snake skins at Howrah station. What will these be used for? On detailing in valuable shoes and vanity bags,” said Sushanta Dhara, representative of the Forest Department for Howrah and Hooghly.

Dhara said the Domjur zila in Howrah has the highest wildlife population in the area. “In my career, I have rescued at least 10 porcupines in the Domjur area. These animals wander into our homes in search of a safe space they no longer find in their habitats.”

According to Ghosh the poachers used to come by train before, “but ever since we implemented checks at the railway stations, they come in pickup vans.”

He added that there has been a problem of feral pigs venturing into farmers’ fields recently. To keep them out, farmers have erected fences charged with 440 volts of electricity. “What ends up happening is that the fishing cats also take these same routes along the drains by the fences, and get electrocuted and die, whether they attempt to breach the fields or not,” said Ghosh.

Sheikh Ayat Ullah, a long time resident of Amta-1, is a groundnut farmer and is extremely familiar with fishing cats. He insists that they pose no real harm for the villagers. He says most of their complaints revolve around a “mad dog” that has been doing the rounds near the village school and has already bitten 10 people.

As for people, a case of mistaken identity recently made Amta an area of concern.

A fishing cat sighting spiralled out of control when one wandered in from the forest one night. Local residents mistook it for a tiger and attempted to chase it down for fear that it was a man eater. The fishing cat was later rescued by Forest Department officials.

“We knew them as bon-beral (wild cat) earlier, it is only recently that we learnt they are called baghrol (fishing cat),” says Ayat Ullah.

How frequently do you see them when you are working the fields?

“Quite often. Sometimes they’ll come to catch fish from the pond, they’ll see me and hide. Sometimes they’ll come and sit by us as we work… We are too used to them to be terrorised by them. In fact, the baghrol is afraid of these pigs that are ruining our fields. The fishing cats are reducing by the day.”

Ayat Ullah’s statement is echoed by other residents, who agree that the pigs encroaching upon the land is a recent phenomenon. The pigs eat and trample the groundnut seedlings, and have even chased villagers at night.

In response the Howrah Jela Jautha Paribesh Mancha contracted Jhalapala, a Dum Dum based youth theatre group, who were on a four day tour across villages in and around Howrah, performing skits for the residents to spread awareness about the fishing cat.

Jhalapala ended their tour in Amta-1 and Amta-2 on October 7 to a rousing response from the residents. In an interactive session with the troupe after the street theatre performance complete with costumes and original jingles, they shared how eye opening the skit had been.

According to Jhalapala volunteers, the audience said they had misunderstood the baghrol and reacted with immediate fear where there was nothing to be afraid of. They said the fishing cat was after all part of their village ecosystem, and deserved a space in it without fear of being attacked.

“It is these responses from the audience that make our work feel worthwhile - when they can relate it to their realities and tell us so,” says Ratul, a member of Jhalapala.

“It’s the children that respond the most. Following the initial yelling and chaos, once the skit starts they become absolutely calm. They watch with concentration,” he said - especially when the animal’s character makes an entrance and when the songs start.

This is the second animal awareness project Jhalapala has undertaken with the West Bengal Forest Department.

Even star species like tigers are often deprived of protected areas. A report earlier this year by the WWF and UNEP states that around 35% of tiger ranges in India are currently outside of protected areas. It also points out that constructions and human settlements coming up near these forest lands deplete the natural resources nearby, prompting the animals to venture into the skirting village areas in search of food.

There is little evidence in recent years of governments in India working to extend wildlife and forest protections from poaching, mining and other industrial activity. Meanwhile, state governments and local NGOs continue to work behind the scenes, attempting to maintain a peaceful balance.

(Bipul, Ratul, Debjit and Madhusree of Jhalapala, performing at Amta-2, Howrah (left to right)).