A Cemetery Tale

“And Lucia loved shall still be Lucia mourned”

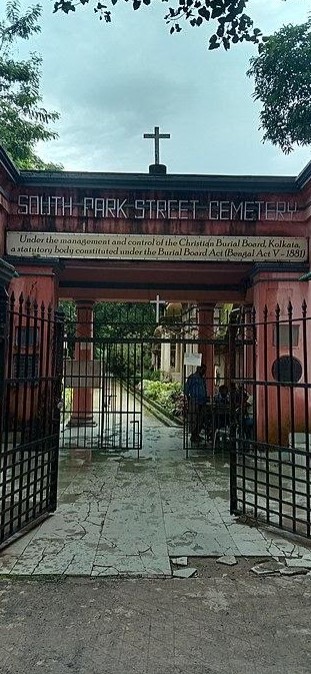

“Why not, the trams aiding, go to the Old Park Street Cemetery?”

What Kipling decided 131 years ago in 1888 during his Calcutta visit on a reporting assignment, I decided too in 2018 on arriving to the city for a journalistic purpose.

Joseph Rudyard Kipling came to Calcutta as a young reporter for the Civil and Military Gazette of Lahore. In fact, he had just been transferred to Allahabad from Lahore to serve the Pioneer, then a weekly.

The newly launched weekly wanted some special stories from Calcutta, then the Imperial Capital of India.

But why did Kipling visit Old Park Street Cemetery?

In fact, Kipling had an appointment with R. Lamb, the city’s Superintendent of Police. But it was yet five hours that he could meet Lamb for some story ideas. As he had heard a lot of the Old Park Street Cemetery or South Park Street Cemetery, including the fact that it had a touch of Charles Dickens, he decided to go there to while away the wait.

“Why not, the trams aiding, go to the Old Park Street Cemetery?” Kipling wrote in his Calcutta diary. As it turned out, he also found an unique story idea at the cemetery. He would write about Lucia Palk, a lady who died young in rather mysterious circumstances.

Lucia Palk, who? Kipling had never heard her name but after research, he took a keen interest in Lucia lying buried in that cemetery. The result was ‘Concerning Lucia’, a short story with poetic touches.

Lucia Palk died some 240 years ago, in 1776. Only a year after her death, the devastating Bengal famine, said to be man-made, or the handiwork of the British East India Company took place, killing myriads of people from starvation.

It made the Santhals revolt against the Company under Tilka Manjhi. During a skirmish with the British, Tilka shot an arrow killing Augustus Cleveland, the District Magistrate of Bhagalpur, who was oppressing the peasantry with an unjust tax burden, and forcing them to cultivate the cash-crop indigo instead of staple food-crops like rice or wheat.

Cleveland too sleeps in the Old Park Street Cemetery, raised in 1690 when Job Charnock purchased the three small hamlets Govindapur, Suttanuti and Kalikata. Those villages would take the shape Calcutta. The cemetery was closed in 1790, some 14 years after Lucia’s death.

When Lucia died, Bengal was at the crossroads of history. Only 20 years before in 1757, Shiraj-ud-Doullah the Nawab of Bengal had been defeated at the Battle of Plassey near Murshidabad.

All those who betrayed Shiraj, including Mir Zafar and Omichand, had shifted to Calcutta from Murshidabad. They feared for their lives as counter-attacks on them by the followers of the Nawab still lingered.

And only four years before Lucia’s death, Warren Hastings declared Calcutta the capital of the East India Company.

Who was Lucia?

She was only 23 when she died.

And Kipling wrote: ‘And Lucia loved shall still be Lucia mourned’.

We don’t have much written history about Lucia other than the references that we get in contemporary, 246-year-old newspapers, which refer to her as one of the most beautiful women of Calcutta. Kipling said she was from Kent, a ‘Kentish Maiden’.

Lucia came to Calcutta from England for a better life, like many other women of her time. She planned to marry some Company army officer or Writer. In Calcutta, she became quite famous due to her beauty. So much so that Warren Hastings himself, then the Governor-General, danced with her at an evening party in Fort William. This shows that she was someone important.

Tilly Kettle, a painter, sketched Lucia’s picture a little before she died. I just could not manage to see that painting despite my best efforts. However, I did learn a little about the scene of her very sudden death, which appears to have been rather mysterious.

Researching on Lucia, I found the Kipling Journal of September 1932, published by the Kipling Society, in which he says she was the “wife of Robert Palk, daughter of the Rev Dr Stonhouse.”

We also have the Company’s records of what would happen whenever a ship arrived at the banks of the river Hooghly from England.

The Calcutta Firangis in those days welcomed a ship with gun salutes and honourably led Memsahibs to the Fort William. But the dream of many such Memsahibs to lead happy, long lives in comfort ended in their untimely death.

The climate of Bengal, viral fevers, malaria, childbirth, snakebites and lightning strikes and other diseases took the lives of many of them. Some died young, some very young like Elizabeth Sanderson and Rose Aylmer.

They all are sleeping in this cemetery.

Rose was only 17 when she died of cholera, within just one year of her arrival in Calcutta from Wales. Elizabeth died at 23 of some unknown fever.

The twist of life of Elizabeth appears like a tragic tale.

In fact, a writer may find several real-life plots that can be woven into a short story on moving around this cemetery.

Let us talk of Elizabeth.

When she landed in Calcutta in 1775, the handsome young soldiers, businessmen and Writers competed with each other to have an English wife coming from England, Scotland, Ireland.

Writers (after whom Calcutta’s Writers Building has been named) were those Firangis who were meant to run the administration of the East India Company.

These young Writers competed with each other to marry any Englishwoman arrived in Calcutta from England. Elizabeth, then considered one of the most beautiful women in Calcutta, charmed many such young soldiers and Writers. Her charm was such that her large number of lovers would do whatever she asked of them.

There is an interesting record of it.

At a dance party, then known as a Grand Ball, Elizabeth once told some Writers that it would be great if she wore a pea-green Parisian dress with pink trimmings at the next ball.

She joked that wouldn’t it be fantastic if some of the Writers also wore a similar dress?

The result was very funny. Her joke was taken seriously.

When Elizabeth arrived at Fort William to attend an evening party, something very hilarious awaited her.

She found 16 young Writers in pea-green with pink trimmings Parisian female dress, something that she had wished for. After the party, all 16 Writers lined up to bid her good-bye when the palanquin arrived to take her back home.

Elizabeth could have married any one of those 16, all of whom adored her. But fate took a tricky turn. She married a gambler, the profligate and drunkard Richard Barwell. Barwell made her life miserable.

She died at the age of 23, soon after childbirth.

How did Lucia die? This is still a mystery. However, the contemporary documents say that after one of the evening parties held in Fort William, Lucia suddenly fell ill. The doctor said she was suffering from putrid fever, and her system required strengthening.

For about a week she was fed with hot curries, and mulled wine worked up with spirits and fortified with spices. But it did not work.

She died.

After some 246 years, it yet remains a mystery, what could have been the real reason of her death? Did some other Englishwomen, jealous of her beauty and the supreme honour of having danced with Warren Hastings, poison her drink?

Did the attention she received from the young Writers make other women desire her death? Did someone among the envious women poison her drink or food? Is is not strange that a healthy young woman should suddenly fall sick and die?

We don’t have any answer to it, even after 246 years.

For me, the Old Park Street Cemetery happened to be an open page of history, especially that of the Santhal Rebellion. This rebellion is associated with the grave of Augustus Cleveland who killed thousands of Santhal peasantry who had risen in revolt.

I spent my entire childhood, adolescence and youth in mountainous Jharkhand which was then known as South Bihar. Today’s Jharkhand cannot be imagined without yesterday’s Cleveland, the Firangi who changed the course of history of this tribal land.

Kipling took a keen interest in Cleveland, who died young at the age of 30 in 1784 when a single arrow shot by Tilka Manjhi pierced his heart. Kipling wrote ‘The Tomb of His Ancestors’ on Cleveland.

Bravo Tilka Manjhi, bravo the Santhal peasantry for revolting against Cleveland!

Cleveland, the cousin of Governor-General Baron John Shore, was then the Collector of the Revenues and a Judge of the Dewanny Adawlut in Bhagalpur under which the Santhal Parganas fell.

In 1777, the disastrous Bengal Famine took place killing thousands of people. The Santhals, an independent natured ethnic group born free, living free and aiming to be forever free in the jungles of Jharkhand, were tortured for tax despite the famine.

It was in this backdrop that Cleveland started forcing the Santhals to pay tax which they just could not. The consequence was Santhal Hool: violent armed rebellion.

The Old Park Street Cemetery is also the final resting place of Walter Dickens, son of Charles Dickens. Dad Dickens received the news of his son’s death on February 7, 1864 after 38 days. Those were not the days of trans-oceanic telegrams. Letters from Calcutta to London would take a month or more to arrive.

The day news of Walter’s death came, Charles was celebrating his 52nd birthday. What a tragedy for the great novelist! Walter died on December 31, 1863 at the age of 22.

Call it coincidence, but Walter and his father’s birthdays are just one day apart: while Charles was born on February 7, Walter’s birthday happened to be February 8.

May be Walter would have lived if had not joined the East India Company as an army officer just before the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 in India.

Taken to gambling and drinking, Walter was named Walter Landor Dickens by his dad, after his poet friend Walter Savage Landor.

Here, we will tarry a bit.

Landor’s love Rose Aylmer also sleeps here in her 221 year old abode. Rose died at the age of 20 having lived in Calcutta for just two short years. Landor, a close friend of Charles Dickens, is known for his elegy on Rose which runs:

Rose Aylmer, whom these wakeful eyes

May weep, but never see,

A night of memories and of sighs

I consecrate to thee.

Walter, second son of Charles Dickens, was first buried at the Bhowanipore Cemetery, then known as the Military Cemetery of Calcutta. But the graveyard ran into dilapidation over the decades. So did Walter’s grave.

In 1911, Walter’s grave came into public focus worldwide, following an article published by the New York Times and entitled ‘Dickens’ Soldier Son.’

After that article, 76 years elapsed.

In 1987, a group of students of English literature at Jadavpur University in Calcutta collected money to relocate the tomb of Walter Dickens from the Military Cemetery, closed in 1790, to South Park Street.

Perhaps Walter could have lived a full life if he had joined a newspaper as a reporter, turning a novelist like his father. But his old man never wanted Walter to become one. He wanted his son to join the army. And the son never wanted to turn a soldier and leave London.

He always wanted to become a journalist and a writer.

Now that was a tragedy!