The System Has Failed Us

How will you be treated in what is perhaps one of the worst and lowest points in your life? #WorldMentalHealthDay

October 10 each year is celebrated as World Mental Health Day, with a different theme each year decided by the World Health Organisation. The theme in 2019 is ‘Focusing on suicide prevention.’ Having been diagnosed with depression a decade ago, and later with anxiety, I have been a user of mental healthcare services for a while now. But I have always been critical of the system and how it operates, having heard and read accounts of other user/survivors and done my own research.

In the years I was a user of mental healthcare services, I never personally experienced the problems I knew existed with the system. I had a good psychiatrist, a good therapist; I was not over-medicated; I was listened to and not treated as incapable, or all the other stereotypical assumptions that follow when the label of being ‘mentally ill’ is given to you.

One of the reasons for this of course is the place of privilege I come from, which enabled me to access the best mental healthcare institutions and practitioners in the country.

Last year in November, a series of stressful events led to my being admitted to the ER of a hospital, to have my stomach flushed of the many tablets that I had consumed.

After regaining some consciousness, I asked the friends accompanying me what was going on and how long I would have to remain in the hospital. As someone who distrusts doctors and dislikes hospitals, my biggest worry was how long I’d be kept here, and having to repeat to the doctors what had transpired.

But to our surprise, the doctor on duty insisted that a medico-legal case be filed, and if we did not agree, they would not keep me under observation.

We told the doctors that under the Mental Health Care Act 2017, suicide had been decriminalised and medico-legal cases was not required, but the doctor on duty said he had no such information. So I was discharged and sent home.

It was of course a relief to not have to stay in hospital, but it left me wondering what would have happened if after being discharged, I had a seizure, another breakdown or other serious side effects from having consumed so many tablets. Would the doctor who refused to keep me under observation be held accountable?

In the hours I spent in hospital, except for asking me which medicine and how many tablets I had consumed, nobody asked me what led me to want to end my life. I was just another patient who needed treatment for a physiological problem, but the emotional and psychological storm in my mind seemed not to matter.

No counsellor or social worker was sent to speak to me or those with me. No information was provided to those around me, in terms of what to watch out for, what kind of care I might need. In that moment, with everything else I was experiencing, what made it harder was the realisation and experience of how the system had failed me. The hospital workers attending to me were not hostile in any way, but they showed none of the empathy or concern one would expect from a healthcare professional under such circumstances.

Following my discharge, fearing that I might be incarcerated or forcibly admitted, I did not want to see a psychiatrist, wanting to speak to one only to ask whether I should continue taking my medication. Little did I think that just this would turn out to be such a huge ordeal. It was days before I could speak to a psychiatrist, without having to be physically present.

The psychiatrist I had been consulting for several years told me she couldn’t recollect who I was, and that if I wanted to consult her I would have to take an appointment (which was not possible then, since I was in a different city). I tried reaching out to other psychiatrists all of whom refused to speak to me over the phone.

Finally, I called an old friend who had studied at NIMHANS, told her of my situation and requested her to connect me to someone who could help me. The person she connected me to was very gracious and heard me out patiently.

But the whole ordeal left me wondering what others faced with similar situations, without the means which are available to me would do.

Here I was trying to do what I needed to for myself. As someone who studied psychology and also trained as a counsellor, I knew what I needed to do and who I needed to reach out to; I just wanted to do it in my own time and on my terms. But the manner in which the whole mental healthcare system operates, if I wanted to seek care, it had to be on their terms and the way they wanted it.

I understand why the system might operate in such a manner, but my problem is with how inhumanely the system treats you in what is perhaps one of the worst and lowest points in your life.

I have felt the need to share my story, because had it not been for the kind of privilege I have, my friends and family who were there with me, and my own will to recover from this setback in my mental health journey, I would perhaps have been just another number in the list of suicides that take place every day in India.

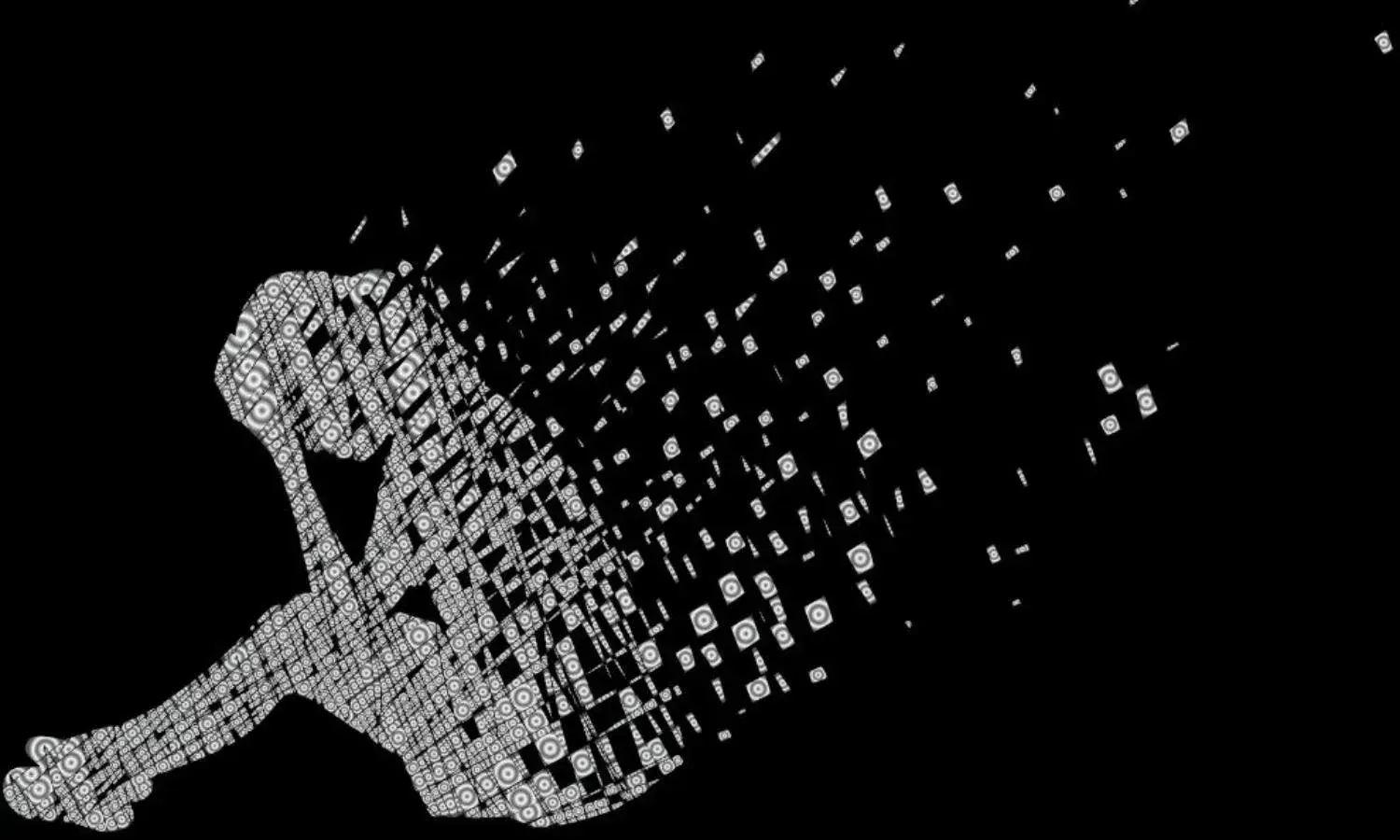

I would perhaps have been one among the many in this country who have taken their life by suicide, whose stories of struggle you won’t hear, but will read about when you read articles on mental health, this World Mental Health Day, telling you about the extent of suicides in India.

What left me most perturbed is that the doctor at the ER I was in, and the many psychiatrists I tried reaching out to, are all people committed to the profession of saving lives, and here there was someone trying to reach out to them to save their own life, but they were more concerned about appointments and procedures, rather than taking out a few minutes and just listening to me.

Even if they didn’t give me the needed medical advice, the least they could have done was heard me.

There are so many individuals out there, some of whom I personally know, whom the system has failed.

The system has failed us by denying us the choice of decision making in our own recovery, it has failed us by labelling our suffering and its manifestation as ‘criminal’, even though the law now states otherwise. It has failed us with the lack of empathy and basic humanity of those who are part of and running the system.