Covid-19: Housing and Sanitation in Slums a Collective Concern

Coronavirus cases in Mumbai's Dharavi slum cross 100

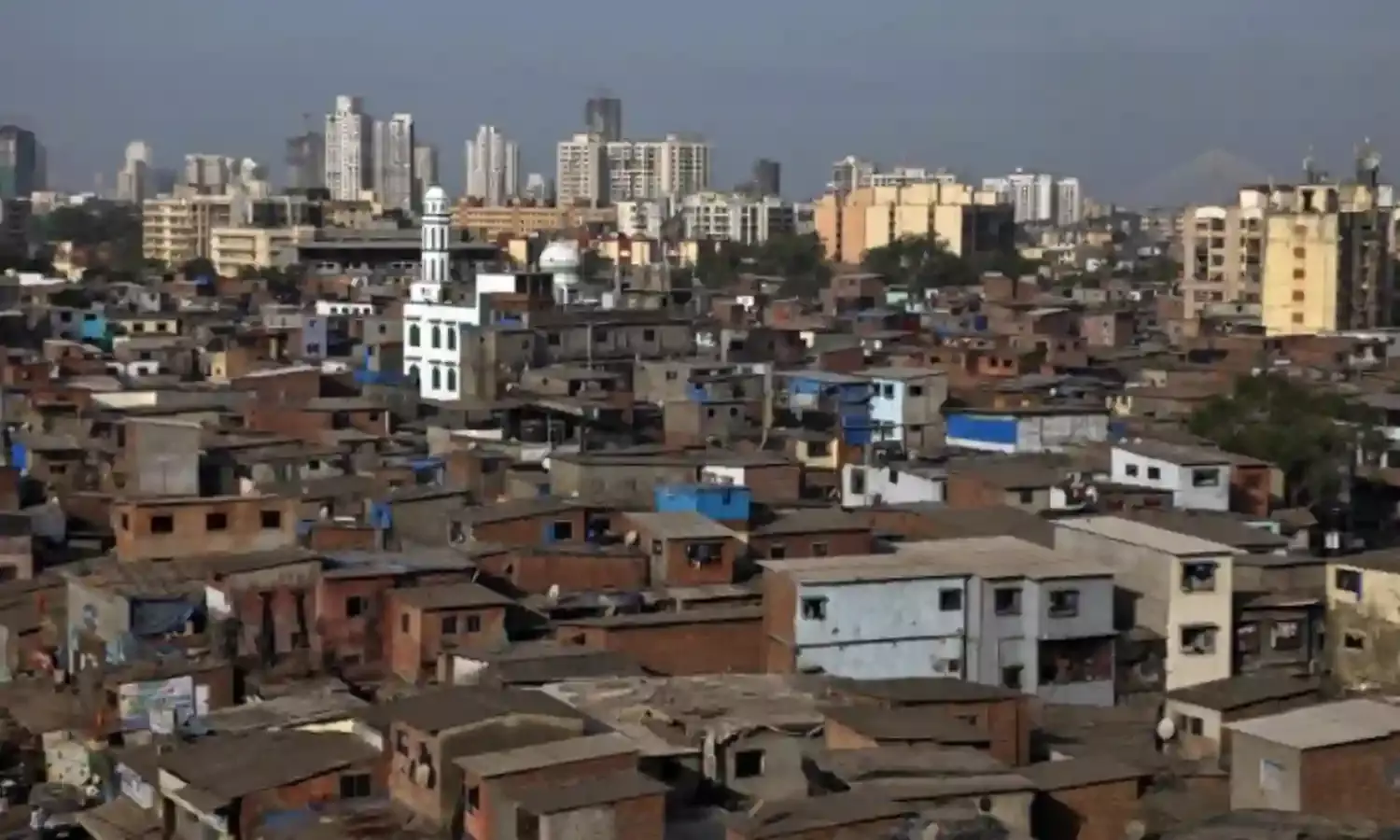

From the wet markets of Wuhan in China, the novel coronavirus has flown its way to the narrow lanes of India’s largest and most densely populated slum, Dharavi, in Mumbai. The enforcement of physical distancing amidst the national lockdown has been particularly strict in slums, which have predictably become hotspots of the infection, adding to the vulnerable residents’ difficulties.

Severely restricted movement and police action are leading to great distress among communities residing in urban slums, where the state does not provide adequate housing space or access to basic facilities such as running water or toilets inside or near homes. This deprivation, and the critical shortage of food caused by the lockdown, are threatening the sustenance of a large section of people.

Housing as a Hurdle to Self-Isolation

According to the 2011 Census 45% of families resident in slums live in single-room houses. The state of housing in these agglomerations poses a huge challenge to implementing physical distancing through self-isolation as has been actively promoted by the state.

With a predictable rise in asymptomatic cases of COVID-19, Naim Ansari, a migrant factory worker in Nawab Nagar, Dharavi says, “Ten of us live together and only one ventures out to buy ration. Each time somebody goes out, we fear getting infected.”

The fear is rightly greater among families that do not have the privilege of living in separate rooms.

Percentage distribution of slum households by number of rooms (Census 2011)

Housing has not been given enough priority in Indian public policy barring a few innovative schemes for income-poor families in urban areas. The scope and reach of these programmes has been marginal at best, when considered alongside India’s overall housing requirements.

Public housing programmes together constitute no more than 16% of housing stock in India. The rest is provided by commercial developers to those who can pay. Even within commercial housing units there exists a division between formal and informal housing, and low-income earners mainly live in the latter: rental or unauthorised colonies entailing slum housing, or residences built without permits on government or private land.

The Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs estimates a nationwide shortage of around 190 lakh housing units, 95% of which deprives people from the Economically Weaker Sections and Lower Income Groups.

A clear paradox lies before us, showcasing the failure of the state and businessmen in the housing sector. Affordable housing is insufficiently available, and the sufficiently available housing is unaffordable. Crores of houses for middle and high-income groups lie vacant, while large numbers of people continue to live in indignity.

A Multi-Dimensional Crisis

Amidst the lockdown, a large number of migrants living in space constrained slums are facing an acute shortage of food, leading to increased susceptibility to diseases arising from malnourishment and unsanitary conditions.

Testimonies from the ground show that the relief packages announced by the central government have not reached the people who need them most. Ration shops in slums open for a very limited time, and are not receiving stocks. To prevent crowding, the police sometimes order shops closed and ‘disperse’ the people waiting to buy food.

Sandeep Mandal, a garment factory worker in Mankhurd, shares how “Once, I had to wait till the next day in order to withdraw cash from the ATM to buy ration. We all live in fear of police violence.”

Several migrant workers stranded across different states are saying that even if they’ve received food grains, what will they feed their infants?

According to a reports citing government figures, since the central government ordered the lockdown, in as many as 13 States and Union Territories, non-government organisations have been more proactive than the state in providing free meals to migrant workers.

In Mumbai especially, NGOs are operating as best they can, exhausting all their financial and human resources while catering to some particularly vulnerable areas.

In this time of crisis the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation has failed to reach out to the most vulnerable people, who depend on food provision by civil society organisations day after day.

The situation has rendered many people desperate.

Fear of Contagion

When it comes to facilities such as drinking water and sanitation, a large section of people are forced to come out of their own homes in order to access them. According to the last census no less than 43% or 59,12,252 slum households have to travel at least a hundred meters to procure drinking water for their families.

A study indicates that slums or scattered settlements which are not recognised by urban local bodies do not have a piped water connection. Furthermore, there is no data on seasonal variation in the supply of water services, underlining how drinking water availability is unreliable even within household premises.

Percentage of slum households by location of source of drinking water (Census 2011)

Government policies address the question of water accessibility in slums solely by considering monetary or technical difficulties. The state has failed to adopt a legal, political and institutional framework that does not tie the provision of water to property rights (WHO, 2015).

It is only the magnitude of the problem that’s become evident to us today, as the availability of clean water is fundamental to staying protected.

People living in slums must step out even to use the toilet. Census 2011 recorded that one-third or 46,73,575 slum households do not have a toilet within their premises. Naim Ansari from Dharavi further shares, “While using toilet facilities, one is afraid to even touch a tap, not knowing if it has been disinfected by the authorities.”

The limited availability and access to public toilets even in a megalopolis like Mumbai naturally leads to overcrowding, an insurmountable challenge.

Housing and Sanitation as Public Concerns

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that the systemic inequality in our countries pose a threat to everyone’s safety and well being. It has revealed the shortcomings of the Indian state’s approach to housing, water, food, sanitation that have garnered special attention only now, in times of peril.

Neither government nor private businesses have effectively addressed these problems over decades. We must have adequate infrastructure in place to ensure the lockdown remains effective, instead of penalising vulnerable communities who bear the brunt of these failures every day, and have it even worse in times of crisis.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in London led to the ‘great sanitation awakening’ in England, wherein the focal point of public health was directed towards preventive measures. The outcomes of the sanitation movement began to be felt by the 1870s – there was an unprecedented increase in average life expectancy in England and Wales (from 40 years to 70) as the state provided better housing, safe water, sewerage, drains.

Few businesses will find it immediately profitable to deliver these goods. The state must be prevailed upon to step up and transform public provision. Food, clean water, dignified housing, and sanitation are just some of many public goods, which require collective action, and benefit everyone.