Zoom Calls, Banana Bread and The Walking Dead

Who will live and who will die?

Just days after a train in Maharashtra mowed down fifteen migrant workers who fell asleep on a railway line, a speeding bus in Bihar ran over and killed six migrant workers on Wednesday. In both cases, the distressed workers were making the long journey back home on foot, as hundreds of thousands of migrant labourers across the country are desperate to get to their villages, stranded without food, shelter or wages in India’s big cities.

I saw the news of the six workers killed in Bihar as I finished a zoom conference call, closing my laptop on yet another productive(ish) work-from-home Thursday. Like most people I know, I’ve settled into a lockdown routine - with my days neatly scheduled into blocks of work, work outs, meals and social time (IRL with family, virtually with friends).

That evening, as my mother and I stared at the oven waiting for our banana-oat bread to rise and our charcoal facepacks to dry, we spoke of how the pandemic has revealed the necropolitical underpinnings of the modern nation state. The visuals of migrants making their way back home on foot - caught between destitution and danger (from the virus itself, but also the journey to their villages) - compels us to revisit Achille Mbembe’s understanding of the use of social and political power to dictate who lives and who dies.

Mbembe was clear that necropolitics is not just the right to kill, but also to expose people (including a country’s own citizens) to death. A strict nationwide lockdown announced with just four hours notice is indicative of the state’s control over who lives and who dies, and the migrants trapped without a means of livelihood are the real-world embodiment of Mbembe’s theory of the walking dead - on how "contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death" forces some bodies to remain in different states of being located between life and death.

As I write this, a whatsapp notification leads me to a harrowing video of an exhausted child, asleep on a suitcase that his mother drags as they make their way from Punjab to their village in Uttar Pradesh, a distance of over 800 km. Minutes later, a news alert informs me that a truck crammed with migrant labourers trying to reach their distant homes crashed in Uttar Pradesh. 23 of the migrants on board - mostly from India’s northern states of Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal - were killed. (This is followed by an alert on immunity boosting green juice recipes to get us through the pandemic, thank you Google algorithm).

Meanwhile, India’s top court rejected a petition seeking directions that district magistrates identify, shelter, feed and provide free transport to stranded migrant workers or those on the move. “There are people walking and not stopping. How can we stop it?” the court responded, thereby absolving the state of its duties to protect and shelter those left stranded.

The necropolitics of covid-19 has been analysed by several scholars. Christopher J. Lee’s article on the subject is particularly useful. In it, he writes: “To be clear, these measures should be pursued. In contrast to normative conditions when such methods would be seen as authoritarian, they are essential for sustaining life in this instance. Taken together, they constitute a reactionary version of necropolitics concerned with the management of life and death—to reduce disease proliferation, mortality numbers, and the rate of infection more generally. However, this reactionary stance equally indicates an unevenness of state capacity, that not all governments are able to respond equally. COVID-19 has highlighted a long-term failure among some states to sustain public health, to sustain life, through their commitment to neoliberal agendas to end state welfare in favor of privatization.”

This unevenness of state capacity is most apparent in India - where even a Rs. 20 lakh crore rescue package unravels when analysed, relying on loans and liquidity as opposed to fiscal benefits. This rescue package comes as many states in India relax labour laws. In Gujarat now, no overtime will be paid to labour. In Rajasthan, labour will now have to work for 12 hours every day for six straight days. Uttar Pradesh cleared a similar move, to extend working hours from 8 hours to 12 hours a day, passing an ordinance that abolished all 38 labour laws in the state. The states say these relaxations will attract investment and boost productivity. But who will live and who will die?

The unevenness is also apparent in our lockdown immobility. I’ve managed to move my entire life into the physical space of my home. Google Drive and Zoom keep me connected to colleagues and friends. A guest room has been converted into a home office. And my ever-expanding home gym has kept my squat and deadlift numbers on track. I’ve found a way to be productive while remaining immobile.

This is in sharp contrast to the hundreds of thousands of workers who do not have the luxury of a self-enclosed physical space, or the ability to control productivity in immobility.

As this article points out: “For the middle classes there is self-enclosure to guarantee immobility. The anatomo-politics – as Michel Foucault named the techniques of disciplining bodies to make them docile and manipulable – of self-enclosure serves to curtail the mobility of the middle classes that travel for reasons of tourism, business, academic conferences, and trade relations. This segment of the population has the income to afford international flights and extreme experiences in the most remote places. But these same people are -we are- those who can work from the refuge of home using a virtual platform.”

This entire stay-home-stay-safe mandate is a Foucauldian call to discipline. Foucault studied the interplay between discipline and social control, concluding that even as we resist discipline, our structures all conform to social control.

In the post covid era, we self-regulate with our work calls, Instagram-live workouts, and gluten-free low-sugar banana bread within the confines of our physical space -- without realising that we are perhaps in-training for a new world that doesn’t question or alter the patterns of production and consumption, but instead, perpetuates inequality through a progressively efficient immobile elite that dictates the forces of production, and a mobile migrant workforce, that is increasingly exploited.

As I light a scented candle and lather on my hydrating night cream, my gratitude for my lockdown routine is tinged with disgust.

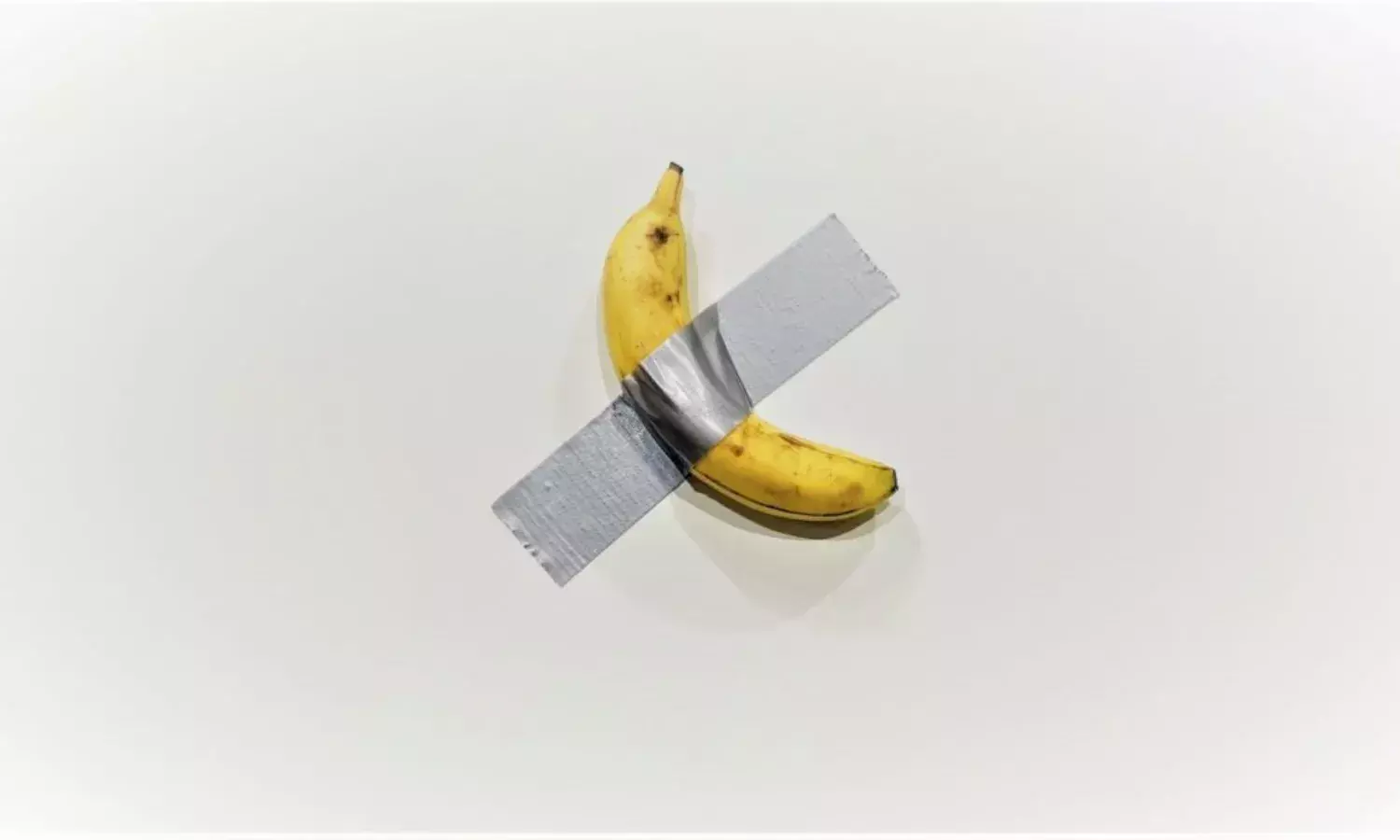

(Cover Photo: Maurizio Cattelan’s artwork ‘Comedian’ - a banana taped to a wall, valued at USD 120,000. The artwork was insanely popular in the art world in 2019, and prompted debate beyond it - including protests highlighting the value of minimum wage labour)