One Nation, Several Cards

Insistent documentary practices cause exclusion

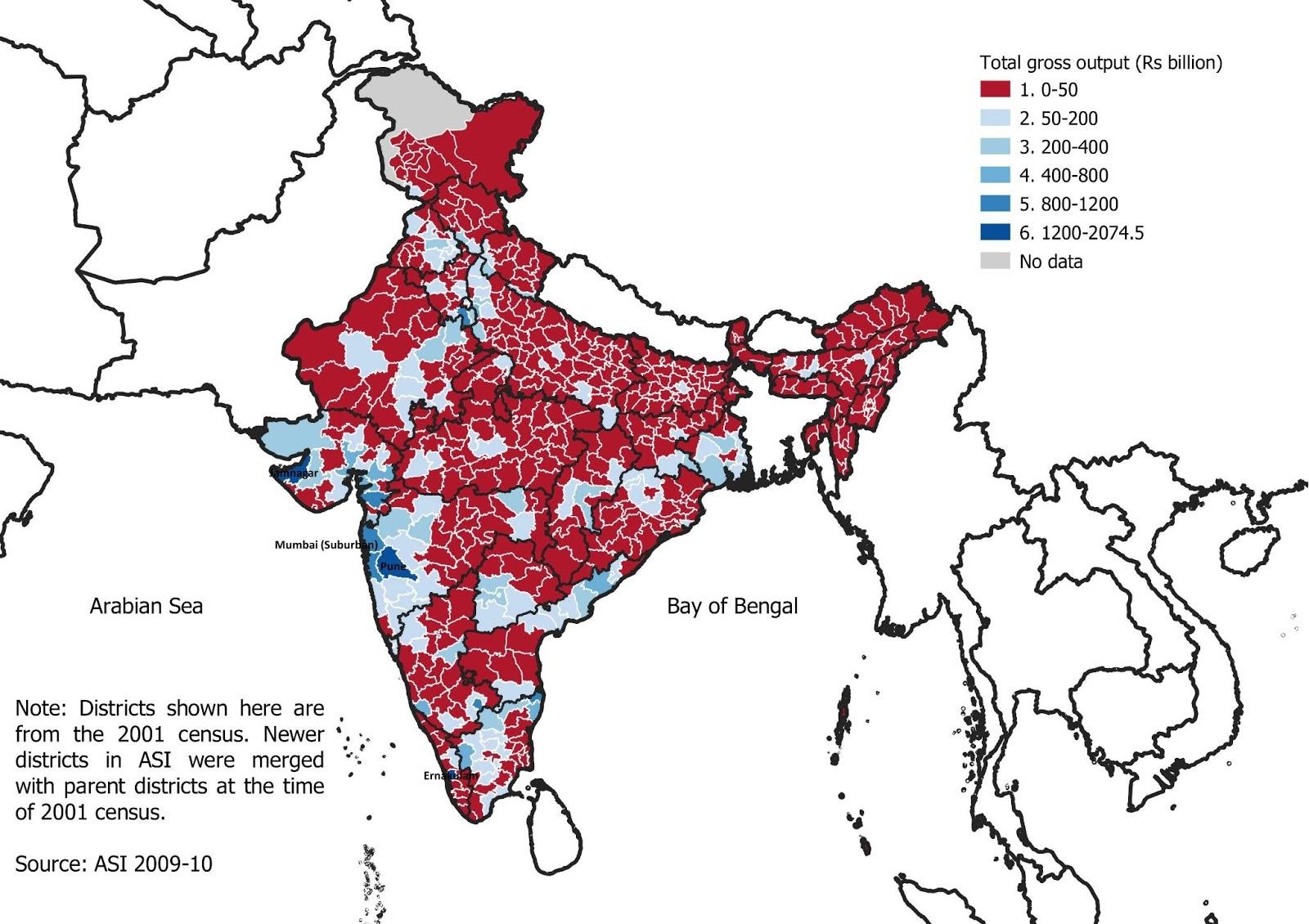

In the Malayalam film C/o Saira Banu (2017) an emigrant worker from West Bengal is killed in a hit-and-run in Ernakulam. The deceased is identified as Kishan Kumar from Minarva Gaon, Siliguri. In court the defence calls another migrant worker to testify in court - who also identifies himself as Kishan Kumar from Minarva Gaon, Siliguri, with an election ID and Aadhaar card to prove it.

The film goes on to say that labour contractors often use the same ID card to bring in multiple labourers one after the other, leaving many migrants with the same documented identity. In a situation where even the victim’s identity cannot be established with clarity, the court acquits the accused of all charges.

The fictional account is resonant with the current state of social security of migrant workers in India. Kerala, in particular, has many immigrant labourers from poorer states such as West Bengal, Assam, Bihar and U.P who now form a significant share of the workforce in the state.

With the subversion of legal norms fairly common in our capitalist models of development, workers hired through middlemen are not given the means to ensure the protection of their basic and fundamental human rights. As in the film, without an identification document they are deprived of equal protection under law.

Such practices of documentation, not just in Kerala, tend to exclude migrants, undoing their rights to food, shelter, safety, welfare, and excluding them from political processes, including representation through affirmative action.

The media clamour last year about the oppression of migrants has largely died out, and apart from the Supreme Court periodically chastising the Union and States for denying ration to migrants, failing to build a unified database of migrants in the country and so on, the issue of migrant workers has been brushed under the carpet.

At the same time, state governments recognise that the vitality of their economy depends on their most crucial workers - migrant labour from far off states and rural areas - and rush to keep their migrant workforce in place.

In many cases, however, their exodus-like march back home during the first wave of lockdowns has been followed by their non-return, and gradual reverse-migration from host states back to their homes.

How did a health crisis turn into a migrant crisis? The answer lies in the fact that state neglect towards migrants is of long standing, with their routine exclusion from public programmes, electoral processes and social recognition in their host cities through red-tapism, nativism, and elitism.

Meanwhile basic utilities, service delivery and even citizenship have been made increasingly conditional on possessing a complete portfolio of ID documents, especially the trinity of Aadhaar, Voter ID and Ration Card which fix you to your address and domicile.

This causes grave distress to migrants, who are constantly on the move.

In Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore, Kolkata the urban poor live in pockets of poverty and destitution. The state treats them differently from law-literate, rule-abiding ‘civil society’. The anthropologist Partha Chatterjee describes them as ‘political society’, those sections of the urban poor somehow able to instrumentalise their political demands.

Others apprehend them usually through paralegal demands, in humanitarianism, moral right, patronage, activism or charity. The state perpetrates violent repression on them in a manner usually escaped by the rights-brandishing members of civil society.

Migrant workers are neither able to mobilise and cohere into any form of ‘political society’, nor to put forward any homogeneous demands to the state. So they fiercely guard their only portal to social protection - their laminated and plastic-protected ID cards, of all kinds, that they spent days procuring.

In order to change the details on one, they often need to lose a full day’s wages, as most updates are made in Seva Kendras that open only on weekdays, or through online portals that need technological know-how, internet connectivity, and access to a working cell phone.

The last census found that migration within states was growing faster than interstate migration. This may be due to rapid urbanisation, rural stagnation, the growth of small cities and the problem of ghettoisation in big ones - another reason is that people who migrate outside their native state risk forgoing crucial entitlements. This includes subsidised food under the PDS, 100-day work under NREGS, and even recognition of Schedule Caste or Tribe status.

For individuals constantly on the move, the arbitrary category of enumeration for ration cards, i.e. the household or family, linked to the residential address, becomes incredibly problematic. One almost never sees an interstate migrant worker (living alone) in possession of a ration card. They almost always leave it behind in their native place for their family to access rations, and purchase food themselves at market rates, despite their meagre and precarious day-to-day income.

During the pandemic this setup has had disturbing consequences, with many migrants being forced to survive on two meals a day, or one.

Over a decade ago, a rationale behind rolling out the Aadhaar card was that it would enable migrants to obtain rations, with the claim being made that without Aadhaar the interoperability or portability of rations was not possible. Yet twelve years later and with nearly the entire population “covered” by Aadhaar, interstate portability of ration cards or the One Nation One Ration Card PDS scheme is only to be found on billboards and posters.

Worse still, arbitrary linkage of the UID to virtually everything (against court orders) has made life difficult for those migrants who still do not have an Aadhaar. There is evidence that squatters and slum dwellers in Delhi have faced eviction threats after listing their shanties as their address to get an Aadhaar, and migrants may well face similar situations.

There is ample evidence also that migrants are excluded from the electoral process by being kept from acquiring voter IDs by the corruption and prejudice of Booth Level Officers, Election Commissioners and politicians. Despite evincing high levels of interest in voting locally, they are unable to exercise this constitutional guarantee.

Often landlords are unwilling to let migrant tenants list their property as local residence for fear of encroachment. In other instances, politicians appeasing the nativist sentiments of local voters find an interest in disenfranchising migrant residents.

Lowered-caste migrants too are vulnerable to cross-sections of exploitation. By migrating, people from Schedule Castes or Tribes are likely to lose the accepted markers of belonging to a marginalised community, thus forgoing entitlements. In some cases, castes listed as SC in one state are not considered to be so in another.

Documentary insistence also erases the increasing feminisation of labour, and female labour migration, invisibilising women to appropriate welfare programmes. Absent a central database of migrants, existing official data rely on surveyors’ listing of ‘marriage’ as the reason women give for migration. [Trans people have also been found to be excluded from having an Aadhaar card at disproportionate rates.]

Although measures have been taken to give women due importance in the National Food Security Act, by listing them as the head of household in the ration cards, the problem of a family divided by migrant labour being unable to access ration remains unsolved.

Kerala boasts of a system of healthcare benefits for immigrant workers ensured by the Awaaz [or voice] card, which is an insurance card meant to guarantee compensation of two lakhs on the death of a migrant to their family, and claims to cover the costs of returning the body home.

However, when a Bengali migrant worker in Kerala died by suicide during the first wave of the Covid19 lockdown, his parents were reportedly unable to find the means to transport his body back to West Bengal due to the transport restrictions, and had to pay 1.3 lakh rupees to have it driven via ambulance the entire way. Even the promise of insurance is either fully dependent on physical possession of the Awaaz card, or the condition that the death was ‘accidental’.

Moreover, the Awaaz card doubles as a ‘labour card’, used by local authorities to keep a check on the ‘Bengalis’ and ‘Hindikaar’ in their jurisdiction. Though meant for all migrant workers, it dubiously targets just a section of informalised migrants working in construction, and not those in the service sector. Most of the former do not know the card entitles them to benefits, while service sector migrants don’t know about its very existence.

These subversive ID practices reveal the nature of our state and its relationship with the poorest. ID cards have been made ubiquitous and synonymous with citizenship and subjecthood. Possessing them changes the material reality of citizens.

During the pandemic, debates emerged on the availability of ID cards for migrants, as without a ration card, many migrants were left starving. And despite the ambitious Aadhaar Unique ID project covering more than 95% of Indians, their government declared to the Supreme Court that it had ‘no data’ on migrants, and thus ‘no data’ on migrant deaths from starvation or suicide.

The arbitrariness of fiscal conservatism and bureaucratic inflexibility in public service delivery are indeed problematic, but even more disturbing is the fact that despite repeated accounts of the distress of migrants from all parts of the nation, and routine persuasions by the courts, even the One Nation, One Ration Card scheme has not seen the light of the day in most states.

Meanwhile ID documents continue to be denied to migrants, subversively used, or remain unable to address their specific needs of social protection and welfare.

Ambuja Raj is an MPhil researcher in social science at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta