Tragedy Unfolds in Firozabad

Endemic flares in chronic underprovision

FIROZABAD: Nisha Begum, 28 and her husband Irfan, 31 lost their five year old daughter while shifting her to multiple hospitals in Uttar Pradesh.

They do not know why she died, and say that none of her doctors showed them her blood reports.

After days of trying numbers, it’s only after her death that a medical officer calls.

“They said how is your daughter Anjum? So I said my daughter has expired. They asked how did it happen? So I gave them the whole position. They said did your daughter have dengue? No, I got none of the reports, no one told me anything.

“So they said we’ll just find her report and tell you what happened. They haven’t called back. I keep calling and they don’t pick up.”

Doctors in Firozabad say that dengue fever, scrub typhus and unspecified viral illnesses have killed large numbers of children in and around the city over the past month. At least 30 children died of this mystery fever during the three days we were in Firozabad.

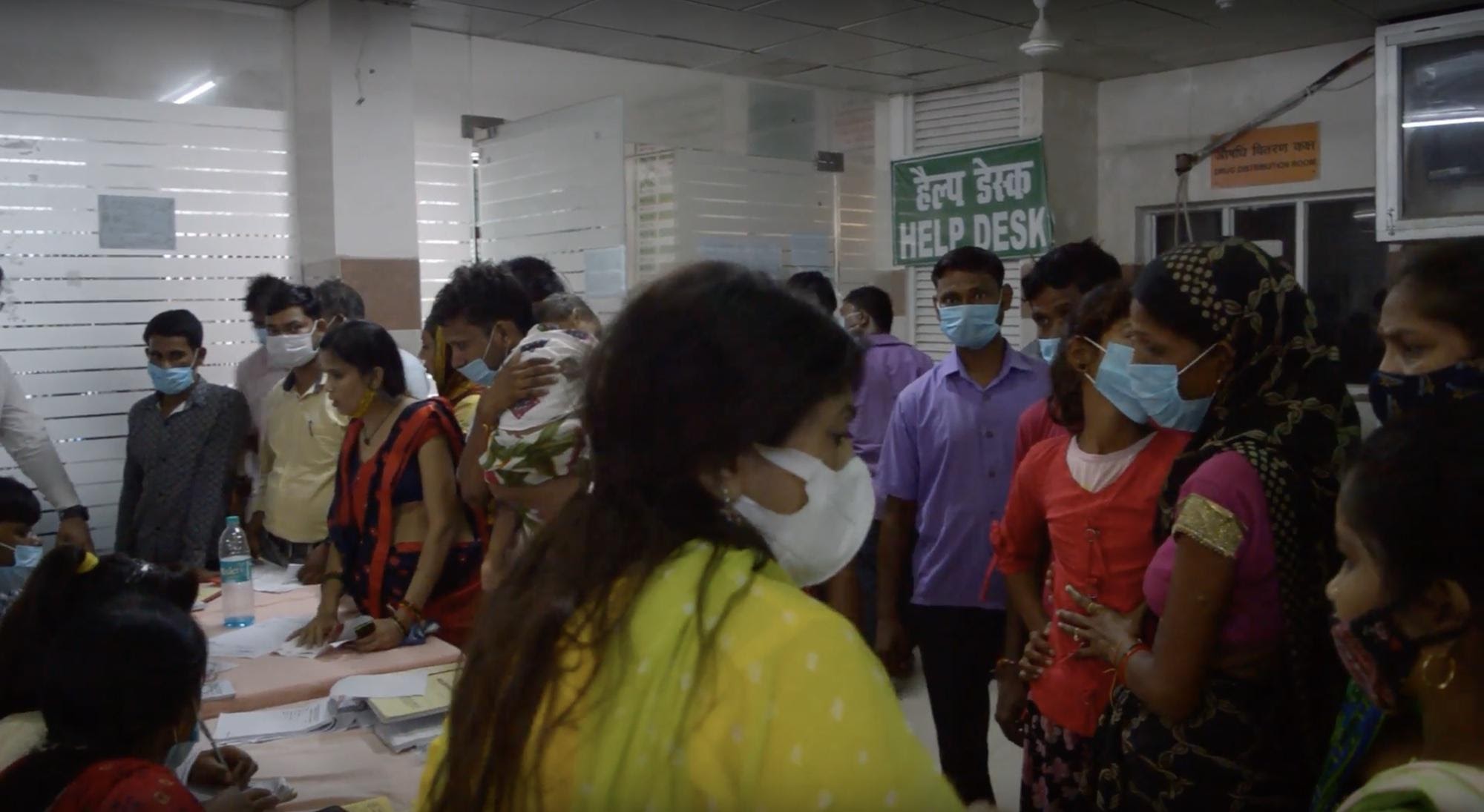

The town’s Sarojini Naidu District Hospital has been fielding hundreds of young patients over the past few weeks. It used to be a medical college but with the rise in dengue cases it was converted to the district hospital.

“We were having few patients, very minimum patients near about 18th of August. After that the cases started increasing bit by bit,” says its principal Dr Sangeeta Aneja.

Soon the paediatric wards were overflowing and permission was obtained to use the hospital’s new ward, built for the third wave of Covid, to treat these children.

“So we shifted all our patients here, and now we are having 403 children. Not all are dengue, but out of that 104 are of dengue, and other viral illnesses.”

The four-storey building, previously not equipped to run as a hospital, is struggling to provide for these patients. They were accommodating multiple patients on a single bed: all of whom were grateful that they at least had one.

The unhygienic conditions at the hospital were jarring, at least for those who gained admission, and posed a very obvious difficulty for patients and their families.

“These rooms are not being cleaned. The toilets are not being cleaned. I am paying 1,000 rupees for a bed for my daughter,” shared an anxious father.

The hospital’s strength has been augmented since the outbreak, and according to Aneja it is now treating over 400 patients in the new paediatric ward. On the visible overcrowding and the many parents alleging neglect:

“No we have been- after the honourable Chief Minister visited this place on August 30 he had granted us many doctors. Among them 30 doctors have been provided from various cities, from various medical colleges, and we have kept 50 staff nurses and likewise 50 ward boys, 100 sweepers more after this.

“So doctors are there, but we have at least 440 beds at this moment which are working in different shifts. Three shifts of doctors are there, doctors are on each floor, so I don’t think doctors are less. It is according to the norms which we have been given. So doctors are not less.”

It was 6.30 in the evening and the hospital had registered 143 patients so far that day. The registration staff would not say how many had been admitted. “Sir I do the entries, not look at who is being admitted or discharged. I don’t have any knowledge of that.”

Asked about the complaints of neglect, “There’s nothing like that. Our doctors are working so hard, our staff is working so hard. What you’ve heard isn’t true.”

About 400-500 children and their families are gathered outside, waiting for a bed. Families are waiting outside the hospital gates with their children, hoping to be let in.

A young girl and her mother and grandmother have been turned away.

“Give her the medicine and the fever stays down. When the medicines run out it returns. Headaches too and she thrashes about. Vomits,” says the mother carrying her girl in her arms.

“Yes, we had her examined elsewhere, gave her medicines too,” her grandmother says. “The fever didn’t go down.”

They are wondering whether to go home.

“What else can we do? They’re not examining her.. When they give us the report we’ll see what to do.”

But medical facilities in Firozabad are not only inaccessible to certain people, but altogether unavailable. The labs were backed up and overwhelmed with patients and samples. Even if the parents were able to get their children tested, in many cases the reports would come a week later, by which time the child’s condition had significantly worsened, and in some cases they even died.

“How do I know why they aren’t admitting her?”

Sulekha and her husband have just been denied admission for their 10 year old daughter Saloni, who has had a fever and stomach ache for two days.

Her husband says they were told there was no room for new admissions.

She says they told her, “Yeh pareshan hai? Upar jake dekho kitne pareshan hain!” You think she’s in pain, go up and see how many are suffering.

She is carrying a prescription and says they were handed some pills. “If they don’t admit her, don’t examine her, what can we do? We might take her to a private hospital, what other option is there?”

Asked about the money for private treatment she says, “We will have to find a way to get the money. We have to make her alright!”

Another father is carrying his young daughter in his arms. With a group of people they have just returned from the hospital.

“No one is telling us anything properly. They’re good for nothing. There is neglect. People are saying our kids are in distress, of course they will be if the doctors are worthless! She wouldn’t tell us the prescription for these three children separately, she just clubbed them all together. They’re all different ages, what if the medicines get mixed up?

“And if you ask they lash out.”

An old man listening next to them breaks into tears.

“Yes sir my daughter is inside, she is suffering. We are unable to get blood, we are very worried. We have been trying very hard. The child is suffering.”

“They asked us to get blood, where do we get blood from? She’s our little girl. We’re so worried, we don’t know what to do.”

Asked how they will obtain blood he says, “We live 20 km away. We’re people who live far off.”

At some of the private clinics and health centres in Firozabad, the situation was chaotic and poorly managed. The premises were unclean and entire families were occupying beds inside wards along with the patients.

We encountered a family in such financial distress that they could not afford treatment for their month-old daughter, who died after a few days of showing symptoms of the fever. Another family spent almost 2.5 lakh rupees on their five year old daughter’s treatment, but could not get her adequate treatment in time, and she too died.

The Citizen spoke to Dr L.K Gupta, head of department and professor at the Sarojini Naidu District Hospital medical college, about the health situation.

“The reason it’s affecting children more is that firstly, the population here is poor. Most of them belong to the labour class, and the nutritional problems are higher and the immunity in children lower.

“Secondly, the children mostly roam around half naked. Without having had their meals the children roam about in half pants. Some younger children, aged four to five years, are loitering without any clothes near the drains..

“The dengue virus festers in unclean water. Even among the recorded incidents, the colonies that run along the drains or gutters show up more cases. Some families that have animals or pets in their houses store the water in cement wells.

“And they leave it be and do not clean the water. Due to these conditions the children are more vulnerable to these ailments.”

What is this fever exactly? Different people are calling it different things.

“It actually is viral fever. Initially even all of us had become alert since there was an expectation of the third wave. So far all of the patients we have treated, we have also had tested for Corona. But thankfully not one has turned up positive. Whereas we have had positive reports for dengue, and the same goes for Lucknow, so dengue is for certain.

“However, not all of the patients are suffering from dengue. The dengue cases are approximately 25% of the lot. As for the rest, the common ailments and diseases that we see during the rainy seasons - stomachaches, diarrhoea, hepatitis, enteric fever, encephalitis, and the convulsions that children aged 6 months to 5 years experience in these cases - these cases are also there.”

Why is the condition worsening?

“The incubation period is approximately 2-14 days. So if we start today with effective fogging, effective larvicidal.. Our DM is working very hard. The respected Chief Minister came and left instructions so we are all working hard. The CMO’s entire team is working on this..

“So once the fogging is done, for about 14 days afterwards we will still see cases. But after 14 days slowly only one or two cases will remain. If we have God’s blessing, soon we will be able to get rid of this. I trust in God and we are working hard, and the administrative authorities are being helpful too. With God’s blessing, we will be able to dispense with this issue.”

R—, 25 has lost her five year old son.

“His poetry books and things from school are all still lying in the house. He is gone now. But he had been sick for eight to ten days. We knew at the time that he was not in good health.”

Was he able to speak to you while in hospital?

“Yes, he spoke to me. All he said was ‘Mummy, give me water.’ That’s all.”

Two days after he developed a fever and stomach pain they showed him to a doctor. A week later he was gone.

“He fell ill on the 24th. He had a fever, we fed him medicines, then his stomach started aching. We took him to the hospital, the trauma centre, they refused us. We took him to a government hospital, they too refused us. They told us to take him to Ashabad.

“We took him there near 2 in the morning and had him admitted him by 3. That whole day and night he was hooked up to a bottle. Then on the 25th or 26th.. we told the doctor his stomach is aching, and he told us to immediately go and buy medicines worth 350 rupees as the fever had climbed back. Then the doctor prescribed more medicines worth 650 rupees.

“From there we went to Agra. There nothing survived. He was hooked up to a machine that was helping him breathe. And then after half an hour he had died.”

Asked what problems they faced with the treatment:

“The problem there was that the doctors were conducting the treatments in their own way. We do not understand what the doctors know or give. Whatever medicines they prescribed, I gave to my child. It was the doctors themselves who came in the evening and gave him the medicine, not us.”

They didn’t admit him to the district hospital? “No, they didn’t.”

What did they say? “They said no. That they cannot admit him.. At the trauma centre there were no empty beds. At the government hospitals they had empty beds. But they just directly refused.”

How old was he? “He was six. Going on six.”

“What is the government doing?” ask the men in the background.

They share that the Chief Minister visited their neighbourhood, the street behind theirs, and that no support or financial assistance was given.

“What can I say? My child has died, what can I say? What can we say about them? It is they who should think about this.. It’s they who should be thinking about what should be done and what should not be done. They cannot return my child if I ask them to.”

Asked if they have ever seen illness like this before:

“I have never seen this before. My children get sick, we give them medicine and they recover. This is the first time I have seen anything of this sort.”

Their younger son is also unwell but receiving treatment, at a private facility.

“It is the government hospital itself that refused us. They didn’t give my older son a bed, how can we expect them to admit this one?” “They will just hand us a tablet and say ‘Take this and go’. What’s the good of that?”

They say the conditions of government hospitals aren’t good at all. They have had to pay around 30–35,000 rupees for private treatment for their sons.

“What else can I say. The Chief Minister comes and the hospitals are cleaned. The government hospital is still somewhat clean. But if you go inside it’s dirty everywhere.. As for the quality of treatment, we took our child. They refused us and we had to leave. It was there that the computers [compounders] told us to go to Ashabad.”

In the background the men discuss the day the police came visiting.

This dengue or fever, why is it spreading?

“Because of uncleanliness, the unsanitary conditions, what else?”

How many children have died in your locality?

“About 8-10 children have died around here in our area.”

“Just today a girl passed away.”

Uttar Pradesh has long had among the worst health outcomes in India, and in its chronic refusal to invest in nutrition, public health, sanitation, education it is little different from most other states.

By 2011 it had achieved female literacy of 43%, on a par with Pakistan, Mozambique, Sierra Leone. In 2012-13 it recorded maternal mortality of 258 per 100,000 births (Sudan, Myanmar, Rwanda) and in 2015-16 infant mortality of 64 per 1,000 births (Haiti, Togo, Afghanistan).

Data from the last National Family Health Survey hasn’t yet been released for Uttar Pradesh.

On condition of anonymity, another government doctor shares his account.

“What is happening is an endemic: when the area is localised but something has spread. So the symptoms are of dengue, they have pain in the abdomen, they are rheumatic, diarrhoea, loose stools, all these complaints are of dengue.

“So we proceed on the assumption that it’s dengue. For the rest we are conducting tests for dengue.. And mainly it is turning out to be dengue.”

“For the cases that are not dengue - It is not a novel disease. It has been there for a while. They tend to endemise. It can happen in any area. If there is dew, waste, waterlogging, collection of water, if no attention has been paid to any of that..

“Then in this season there are more mosquitoes. Aedes is why it spreads. And with collection of water and so on mosquitoes proliferate, which is why in a local area it starts spreading.”

We ask how they are preparing for future waves.

“Preparations.. it’s the usual. The manpower needed is not available. Only very slowly have doctors been made available here. From Atari, Kanpur, Agra, Lucknow, Saifai, quite a few doctors have come. And in that way we are giving coverage.

“For the rest, slowly, progress is happening. The number of patients is coming down, critical patients are also coming down slowly. Considering this, it seems that slowly it will be damped. And things will return to the way they were.”

We visit a locality in Firozabad where 5 to 7 children have died in the past week. Here the situation is worse. Most of the residents are hardly able to afford doctors for their children, and they end up going to the family health centres close to where they live. The compounders there are not able to provide proper care and treatment for the children. Most are confused as to what kind of disease this is and how it is spreading.

These areas are vulnerable and in need of better health and sanitation infrastructure, and planning. Wells are being dug in multiple areas that bring up dirty water and fester mosquitoes and disease-carrying germs.

“Aaj bhi do khatam ho gaye,” says a woman who lives here. Two more died today.

“We need a paved street made here,” says another.

“A lot of people have visited this place, a lot of journalists too, and we have been running around in a lot of difficulty too for a long time,” says Mohammad Azad, 29.

“We go to the Nagar Nigam and sanitation workers come from there, and they say all sorts of things. They tell us to clean up the water from here. But where will the water go? We need drainage and facilities to deal with the water.

“This street should be developed. We’ve been a week without electricity.”

The woman next to him says, “Mosquitos are eating us alive. And the heat. There are no drains, the water is filling the street.”

“Go look at all the streets here, look at the condition of the streets here. Can anyone get out?” says Azad.

Another woman says, “Government, what government? Governments only look out for themselves. Does anyone look out for others?”

“We are afraid of this sickness,” says Azad. “Unnumbered people are dying. A week has passed and five children have died here. This is what we fear. We are afraid of falling sick. Every day there is a death in someone’s home.”

Another area resident makes an appeal to anyone listening.

“Yes, I am —— and I am a resident of ——. There is so much difficulty here with the water coming out, water fills up from all four directions. If someone dies it will be so difficult to get them out.

“All of you can see for yourself how much water has filled up here, in the morning. If all you viewers can do anything about this - that a street is built for us and we do not have to suffer. It is so difficult, when the water fills up it comes to my knees and it’s hard to move about.

“Small kids are suffering a lot. And with the illness spreading, kids are dying, dying in great numbers. 7 deaths in 3 days. This is how many kids are dying because of sickness.

“Now you all tell us, what should we do? If the government can do something for us that is a good thing, otherwise we here are just curling up and dying.

“Look at what our conditions are here, look how much water has filled up. This is supposed to be a street, would anyone call it a street? It’s like we’re standing in a field.”

“Dekho samundar,” says another man. Look, the sea.

“We have been taking care. I myself take rounds in the morning with all the doctors,” says Dr Sangeeta Aneja. “I myself ask the doctors to tell me the condition about each and every patient, in the morning as well as at the night. In between all the doctors visit them.”

So you’re saying the situation is under control?

“Yes, now it’s under control. Now the patients are more, but that much critical patients are not there because they’re aware of it - the relatives are aware of it, that they should come to the hospital early. They are having faith in us, and coming to us when they are having mild fever, vomiting, diarrhoea. So it is controlled way more.”

But I saw unconscious kids in the waiting room.

“No, doctors are there. It’s not that thing. Doctors are definitely there from morning till evening, 24 by 7. Sometimes patients are not satisfied, because they’re thinking that we are not getting relief within one or two days. They are habituated that we will get some strong medicine from a quack or a nearby medical store, and they’ll get a quick relief.

“But that is not the situation in dengue or in viral fevers. Something that is self limiting, minimum medicines are given.”

Can you tell us something you remember about your grandson?

“Of course one misses one’s children. Why wouldn’t I miss him? In the morning on my way out I would give him some money for snacks. And in the evening he’d grab the cycle and say ‘Let’s go Baba!’”

“A child is made of love isn’t he? Even if we fought, he was my grandson. He was handsome, he was good. That’s what he was.

“And he was loved. All of us lived here together. His closest relationship was with me.

“And his father too of course,” he points grudgingly.

What did you want him to study and to be?

“Study? He was six! He could barely count to a hundred.”

Most of the doctors we spoke to could not pinpoint this mystery fever. Some called it viral fever while some said it was scrub typhus.

What the young victims’ families shared was a desperate experience of their children’s last days, in a starved health system that only met them with a fatigue response.

“Sir, no one heard us out. I folded my hands, I touched their feet. No one heard me out.” Anjum’s grandmother.

Her mother recalls. “On the morning of the 8th my daughter had a fever around 4 am. We rushed her to the OPD and had her examined. But sir because we were late her blood sample couldn’t be taken that day.

“After that on the 9th her blood test was done. On the 10th we got the report. After getting the report I pursued the doctor so he couldn’t turn me away, but he kept saying take her to the district hospital. We brought her back home.

“We live on rent in — Nagar where a camp was set up. I had her examined again and they said it was to check for dengue or malaria. I said when will I get the report? They said if your daughter is positive you will be told tomorrow over the phone.

“On the morning of the 11th I took the girl to hospital to get her admitted, but the people there said there were no empty beds. Everyone refused her admission saying there are no empty beds. They had me go to the new building.

“As soon as we got there the doctor didn’t check her fever, didn’t examine her at all, just passing through he gave her two injections and hooked her up to a bottle.

“When the bottle was being hooked up my daughter had a piece of apple and two Parle biscuits. When she had finished and the bottle was empty they attached another. My daughter said I am feeling cold.

“I immediately complained to the doctor - she was a madam - and the madam said to switch off the fan, so I switched off the fan. But my daughter was still feeling cold and I told madam, so she removed the bottle.

“After the bottle was removed my daughter said I need to go to the toilet. As I took her to the toilet my daughter passed a stool. Bringing her back from the latrine and laying her on the bed I told the doctor my daughter has passed urine and a stool at the same time. Right after that she also started vomiting.

“After vomiting she passed a stool again and I again called the doctor. The doctors kept saying We’re coming, We’ll see her, We’re coming, We’ll see her. My daughter passed a stool two or three times on the bed itself.

“As she was in that condition the doctor came and gave her another injection, and my daughter stopped speaking. She closed her eyes, turned away and became unresponsive.

“Then it started raining and the doctor immediately called the district hospital for an ambulance, and the ambulance came. My daughter went in the ambulance with a bottle attached to her and they started administering her oxygen there and in the ICU.

“Then a doctor named L.K Gupta examined my daughter as well as another doctor who had come from Lucknow. A lot of computers also examined her. Then they hooked her up to oxygen and a machine, but only a little while later told me to take her to Agra.

“I folded my hands in front of L.K Gupta and begged him sir, please keep her here, treat her here, I don’t know Agra. He said that hospital is attached to this place and you will get good treatment there.

“Less than two hours later my daughter is convulsing violently and they gave me a referral for Agra.

“I told them give me my file. I went downstairs for a blood test and they again took my daughter’s sample. I told them give me my daughter’s report so I know how many platelets she has and whether it’s dengue or what. But no one gave it to me.

“I even folded my hands to the madam who gives out the reports. I even went inside the lab and folded my hands in front of the sir who was examining reports on the computer, begging them to give me my daughter’s report. No one gave it to me.

“A brother even helped me. He was a patient there - he was with someone who had been admitted - and because of me he folded his hands saying give her her report, her child is serious. But no one told me anything.”

Did the doctors treat your daughter?

“Yes the doctors treated her, but they didn’t examine her. Her fever, what was wrong with her, they didn’t examine her at all. As soon as we got to the new building they gave her two injections and a bottle. This is why my daughter’s health got worse. My daughter was fine.

“And if it was dengue or any of that, then what about the examination at the — Nagar anganwadi camp? I got no report from there either. And I’ve been calling them and they’re not even picking up the phone. And at the hospital no doctor ever examined my daughter. Right when she was admitted, in passing the computer gave her two injections and a bottle.”

“She was fine when she left, she was talking, she spoke to me,” says Anjum’s grandmother. “I asked her what’s wrong and she told me I have a fever.”

How old was she?

“Five years old.”

“She kept on asking for water. At the hospital I told the doctors my daughter wants water. Then even in the ambulance she was asking for water. But the doctors refused saying she is on oxygen, don’t give her water. The ambulance operators refused, saying don’t give her water.”

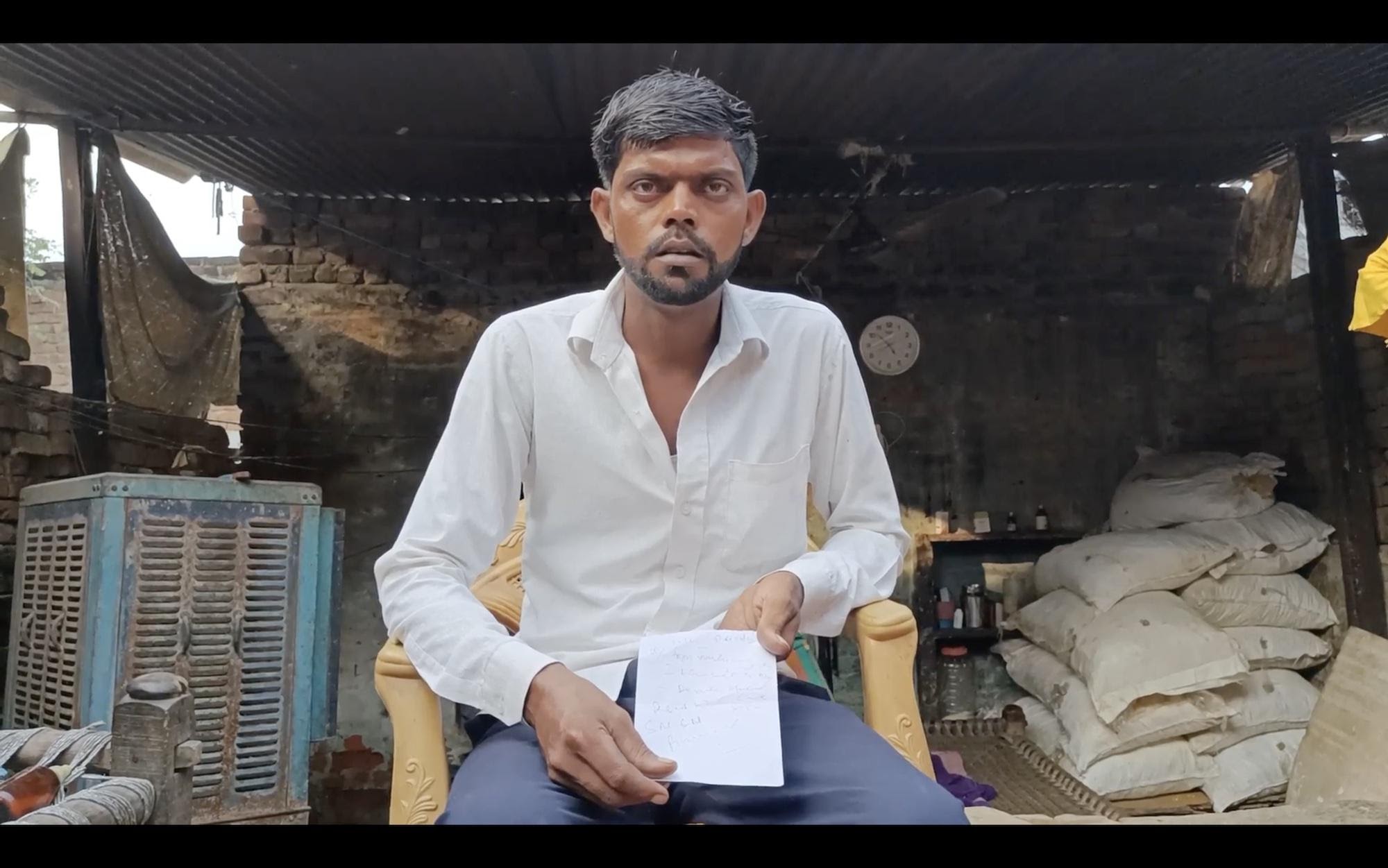

Iqra, aged a month and a quarter has died. Her father is distraught.

“Just today I got medicines for 1000-1,200. I’ve been getting medicines since the day she fell ill.”

“The government is not interested in helping us brother, what do we do? I’m a poor man, what should I do, die?

“There’s been no electricity for three days.”

“We are suffering. The water supply too comes and goes,” says Iqra’s mother.

“This is what I want to say about my children—”

“Look it’s poor people’s children who are dying.”

Did you show her to a doctor?

“We went to many doctors. 2-4 doctors. Laid her prone, massaged her arms, but she got no relief.

“Today I took her to Deepak’s, said take the 1000-1,200 rupees, and he says brother..”

When did it happen?

“She was a month and a quarter.”

No, when did it happen?

“Now, just now. She died around 4 o’clock. Ate the medicines, choked and and fell unconscious. Her limbs were cold.”

“Her health had worsened the last two days, because there was no electricity.

“And today when I got medicines from Dr ——, the minute I gave her the pills she died.”

“It would have been only 3 or 4 days that she had a fever.”

“We had two together, twins. The girl is dead, the boy is alive.”

“No, no one’s ever come to spray this area. No karamchari.”

“We tell them but no one comes to clean.”

“What else do I want to say. This is what I’m trying to say. My child is dead.”

With inputs from Sreya Deb and Aman Hasan Kumar