50 Years Hence, Satyajit Ray Reminds Us of Hunger

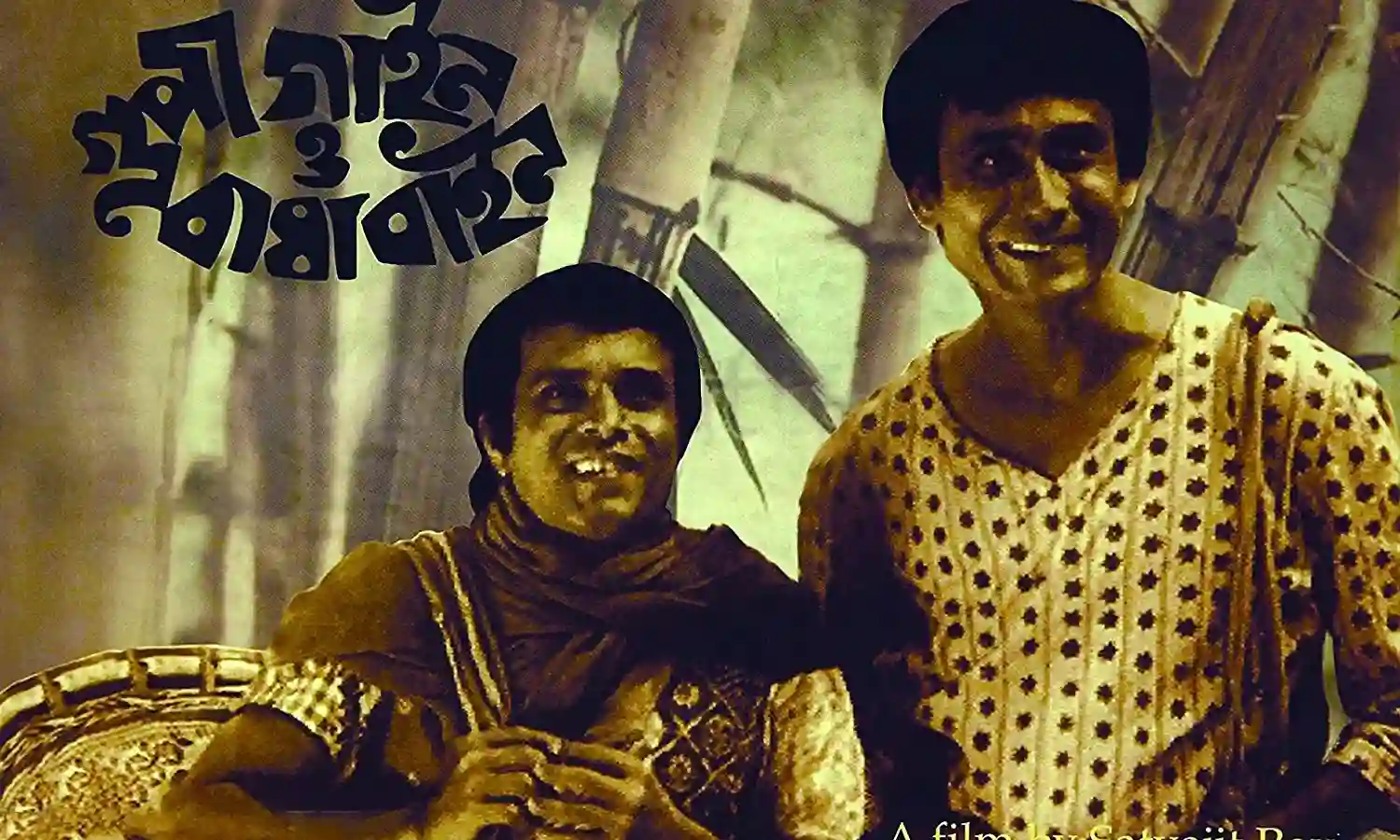

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne

Hunger is not a question of fate; hunger is the result of human inaction. Few of these hungry people are conscious that the right to food is a human right protected by international law.

The small number of people that might be conscious is too busy struggling to live from one second to another, looking for food. The right to food is “the right to have regular, permanent and unobstructed access, either directly or by means of financial purchases, to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensures a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free from anxiety.”

Governments have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil the right to food.

Ray’s treatment of food and hunger was subtle and low-key in most of his films except in the case of Indir Thakrun, the doddering old aunt of Apu and Durga who was desperately hungry but Sarbajaya, her sister-in-law, had no mercy on her. It was Durga who stole a few green chillies from her mother’s kitchen to give to her old aunt. Sarbajaya herself was desperately in want of food for her kids so one cannot blame her for her cruelty towards Indir Thakrun.

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, Ray’s only fantasy film celebrates fifty years since it was first released on May 8 1969.

It would be interesting to explore the role hunger plays in the film.

In Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne adapted from Ray’s grandfather, Upendra Kishore Roy Choudhury’s fairy tale fantasy for children, food appears as food per se, as an irony in a land with a cruel Prime Minister who drugs the real King and keeps him swinging between childhood and violence. At the other end, the same prime minister forces the poor peasants to pay tax when their lands are dry, arid and unyielding, or put them behind bars if they cannot pay their tax.

Hunger also functions as the harbinger of peace in a war-torn situation where soldiers are underfed, skinny, hollow-cheeked, hungry and too weak to fight a war. The camels too, a skinny, tired and look too hungry to support the soldiers.

Hunger is a parallel story that ran alongside the fairy tale of two innocent villagers blessed by three wonderful boons by the Ghost King. The first boon Goopy and Bagha asked for is, “We wish we could go wherever we want to and eat whatever we like to.”

Two huge, decorated circular silver plates surrounded by beautifully curved silver bowls suddenly appear before them by magic and one by one, items of food fill up the two plates and the two poor and hungry villagers begin to dig into the food at once. This is one side of the story. The food in fact, is so much and so varied that the two forever hungry souls soon leave their silver plates while Goopy throws some leftovers at a waiting and hungry dog. This perhaps suggests that even the desperately hungry can throw food away and give it literally to the dogs.

Ray stressed on the hungry faces sharply and repeatedly to show the tremendous hunger among everyone in the Kingdom of Halla including the soldiers. In one scene, the King’s cruel and cold-blooded minister bites off a chicken leg and as a prison guard stares hungrily at the chicken leg he is relishing, the minister asks, “Why are you so greedy, man?”

The appearance of the guard – skinny, skeletal with hollowed out cheeks, his expression and his bent body spell out that he has probably not eaten for days. In another scene, the messenger, portrayed by Chinmoy Roy who was extremely skinny himself, says with a toothless smile, “I have not eaten for days, Sir.”

When war is declared between the army of Halla and the army of Shundi, Ray needed an ‘army’ of junior artistes to create the scene. How would he manage such a huge crowd of skeletal people with deeply burrowed eyes and hollow cheeks? Ray decided to take his team to Rajasthan to shoot the war sequences. The spot chosen was a desert without a single plantation or tree.

The only people wandering across the desert were camel riders who belonged to a gypsy community. These people had no water to drink and the only food they had access to were week-long roundels of dry bread and a rock of jaggery. It was an extremely hungry community starved of food. So, when they were asked to appear in the film as soldiers of Halla’s army, they agreed at once when they were told that there would be lots of food and very good food. When the shots of pots of sweets falling from the skies were taken, they pounced on the food and the shots had almost the effect of a documentary film though the audience remained unaware of this.

This was a strange and tragic intersection between the reel and the real. The war scenes in this sense, define a situation where two different kinds of history have merged – the history of real hunger with the history of a film that carried a strong undercurrent of hunger. But does this not also point out to the filmmaker exploiting a large group of very hungry people to invest his war scenes with the feeling of the real? What happened to those hungry gypsies after the shoot was over? No one knows.

Through a beautifully cut sequence, we see the child-like king of Halla grabbing an earthen pot filled with rosogollas given to him by Goopy and Bagha after the war is destroyed. They want to take him to his brother in Shundi. He keeps gobbling up one large-sized rosogolla after another which is a very un-kingly like behaviour. This is perhaps an indicator that he too, was kept starving. Goopy and Bagha pick him up and the scene immediately cuts to the three of them landing in Shundi’s court while the King of Halla unaware of this trip, keeps at his rosogollas with great joy.

As urban elites play with their plush limousines and multi-functional air-conditioners, enjoy a more diversified diet and reduce the resulting adipose tissue in slimming clinics, little do they concern themselves about how the same neo-liberal policies that have benefited them, have, at the same time, enmeshed millions of their country-men and women in deep debt and land loss reducing their lives to a struggle to barely survive as humans. A former government’s insistence on hunger and starvation being a “voluntary choice” reminds one of one Marie Antoinette who, before the French Revolution, had advised her starving subjects to have cake if there was no bread.