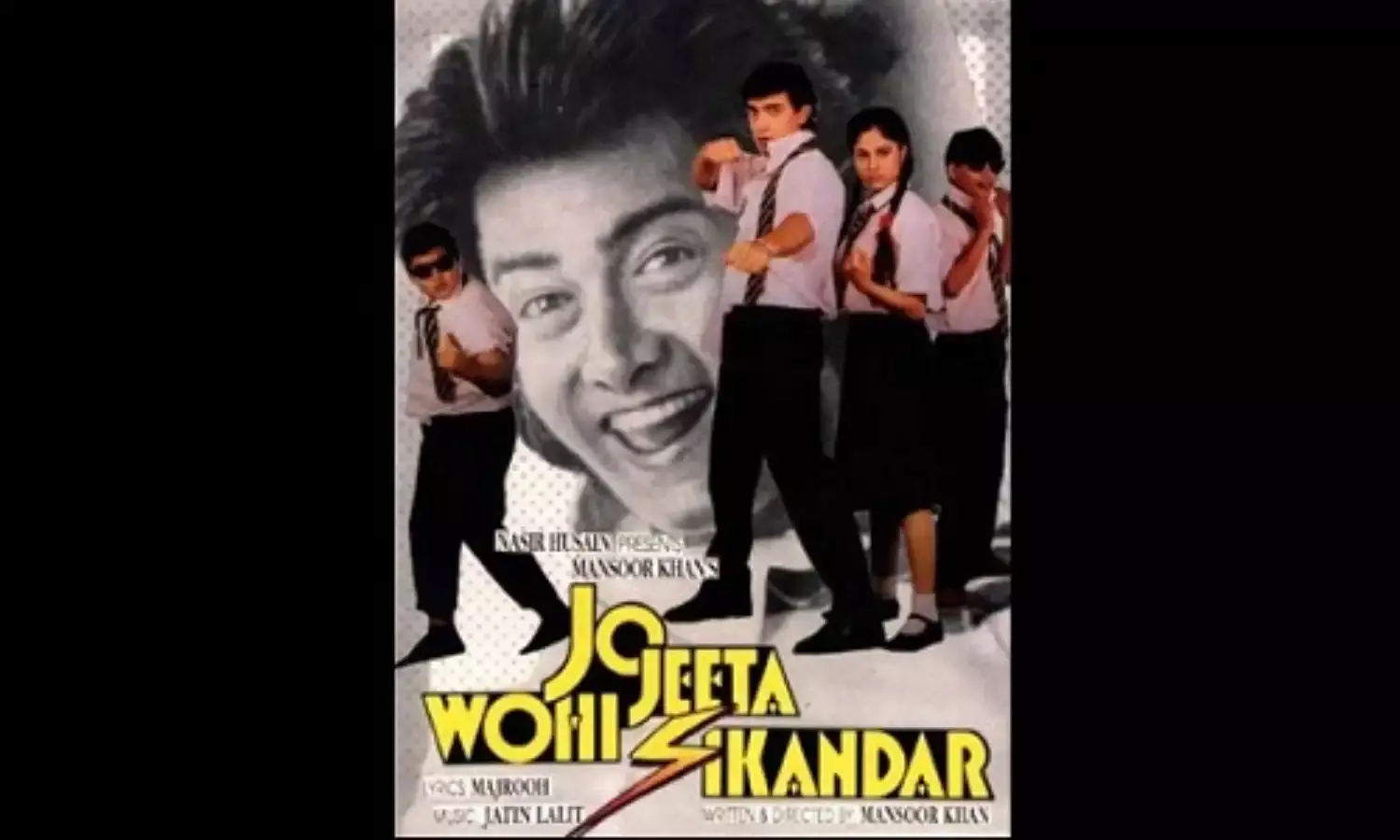

Looking Back On Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar 27 Years Later

Sterling performances and music, and a strong story, make it well worth the rewatch

When Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar released on May 20 1992, it redefined mainstream Indian cinema by not catering to the established clichés commercial Hindi cinema was replete with. It did not feature a dozen villains and a super hero trying to bash each other up for God knows what reason. The film contained an electric energy that vibrates throughout it, throbbing with a life of its own, inviting the audience to participate in the climbing suspense, in the lives of two brothers apart from one another and yet so close.

There is this warmth that comes out of the screen and touches your heart. That soft, understated touch of romance that tugs at your heartstrings. And there is fun, speed, movement, dynamism that tells us what mainstream entertainment is all about.

The young have a lot to learn from the film: that the power of performance is greater than the power of affluence and influence. That honesty still pays and dishonesty doesn’t. That love, friendship and attachment to the family are values cherished over the values of physical and money power.

In a manner of speaking Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikander is an anti-violence film. Not that it does not use violence. There is blood and gore and a dozen-odd fisticuffs and bashings up. But every such fight has a rationale: the rationale of an angry youth trying to assert its identity in a world filled with conflict, competition, both healthy and unhealthy, and confusion.

The overgrown “children” might have looked absurd. They do not because they are incorrigible repeaters. JJWS unspools the story of an ordinary young school boy who fails every ear, smokes on the sly and breaks every rule in the school book to lead an easy-going life. He has neither motivation nor ambition. His only function is to gallivant around with his equally purposeless friends, also repeaters, and to use the young girl who loves him for his own needs. His older brother is his exact opposite: a good guy motivated by his father who runs a modest restaurant run by the older boy.

The story is about the younger Sanjay’s dramatic journey from a sense of self-derived freedom to responsibility, from feelings of deep guilt to resurrection. He changes from being a happy-go-lucky young gallivanter to one motivated by excellence.

It is about how he learns the meaning of life: that excellence is more important than revenge, that love is always a better emotion than hate or anger.

Nothing however, happens overnight as if by the touch of some invisible magic wand. Mansoor Ali Khan who directed this film after a thundering debut in Quayamat Se Quayamat Tak throws up a rationale for every incident that happens in the film. At the same time, JJWS contains every gimmick in the mainstream book: fights, love, revenge, jealousy, competition, humour and a bit of cheesecake a la Pooja Bedi imitating the Marilyn Monroe skirt-blowing shot in The Seven Year Itch - and each of these arrives as a relief.

There is a lot of punch and ready wit in the dialogue. The laugh-lines are riotous in their pithy humour. The characters are fleshed out very well, and gain depth as the narrative unfolds.

Excellent performances by all the actors except Pooja Bedi as the gold-digging girl enrich the film. Aamir Khan who was still wet behind the ears, and the debutant Makin as his older brother Ratan, perform very well. Kulbhushan Kharbanda convinces as the single-parent father of the two boys. Deepak Tijori as the attitude-filled Shekhar full of boasting and ego does well. Deven Bhojani and Aditya Lakhia as Sanju’s close friends are also good, but Ayesha Jhulka gives a sterling performance as the naïve young girl in love with Sanju.

She helps Sanju practise cycling for a competition. Cycling as a competitive sport has hardly found place within the realm of Bollywood cinema. In JJWS it is used extremely well as a point of motivation, a severe tussle between the egos of two groups of students, an example of excellence that demands qualities like discipline, honesty and integrity, and as an agent of individual and social change.

It helps bring about a radical change in the character of Sanjay, who was never attracted to competition but makes it his goal to win at the annual race in place of his older brother who is grievously injured. The environmental benefits of cycling as a sport come across with the place setting of Kodaikanal.

The choice of Kodaikanal as the locus of the story enlarges the canvas and infuses the script with a typically Indian rather than a regional flavour. The art direction by Nitish Roy and Shibu is earthy, real and stripped of glamour. Najeeb Khan’s cinematography makes the best use of colour and slow motion as the film moves around from the modest restaurant to the town square, to the mall through hilly winding roads as the boys practise their cycling.

It is the editing perhaps that might have been tightened a bit. The film spells out repeatedly, in a hundred different ways, the meaning and significance of non-violence, honesty, hard work and excellence and above all, the message of love and friendship.

The lyrics by Majrooh Sultanpuri set to music by Jatin-Lalit have been immortalised through repeat viewing on television, YouTube and other channels - they are so hummable and so good! Pehla Nasha is placed in a surrealistic love scene where some of the shots are in slow motion. Yahan Ke Hum Sikandar is a beautifully orchestrated number choreographed and composed distinctly with games and sports, and of course, cycling. Rooth ke humse kahin jab chale jaogey is a soft, melancholy number that moves into flashback to show the two brothers when they were small and some clips are from an earlier film.

Galyat Sakhli Sonachi is a beautiful Goan folk song used as the opening of a song number in the film Arey Yaaron Mere Pyaaron - it is the dance competition song that is beautifully conceived with the underdog in mind, defining the class distinctions between the “pajama-clad” Modern School gang and the elite gang.

Each song is distinctly created to suit a particular situation and the choreography matches the music and the lyrics. Sad, however, that Jatin-Lalit could not sustain the excellence of these compositions later on in their career. The singers too, were comparative beginners at the time, such as Alka Yagnik, Sadhana Sargam, Udit Narain and Amit Kumar, and did a wonderful job.

Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar defined a benchmark for Hindi mainstream cinema to show that a masala film, besides offering wonderful entertainment, can also narrate a powerful story filled with hope, for, by and of the young.

Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar netted ₹4 crore in India, equivalent to ₹71 crore or US$10 million adjusted for inflation. Mansoor Ali Khan went back to the US after this film, and the fact that it turned out to be a big box office hit could not tempt him to stay back. But 27 years later, you would still want to watch it, because it has timeless repeat value.