Chhoto Chhobi: An Experiment with Form

Watching films within a play is an uncommon experience

Sohag Sen celebrates fifty years in theatre this year. Some of her plays, under her group banner Ensemble, have kept their footprints on the pages of the history of theatre in Kolkata. She is also very much in demand for workshops by film directors in Bengali cinema, and has functioned as facilitator for many actors, directors and films.

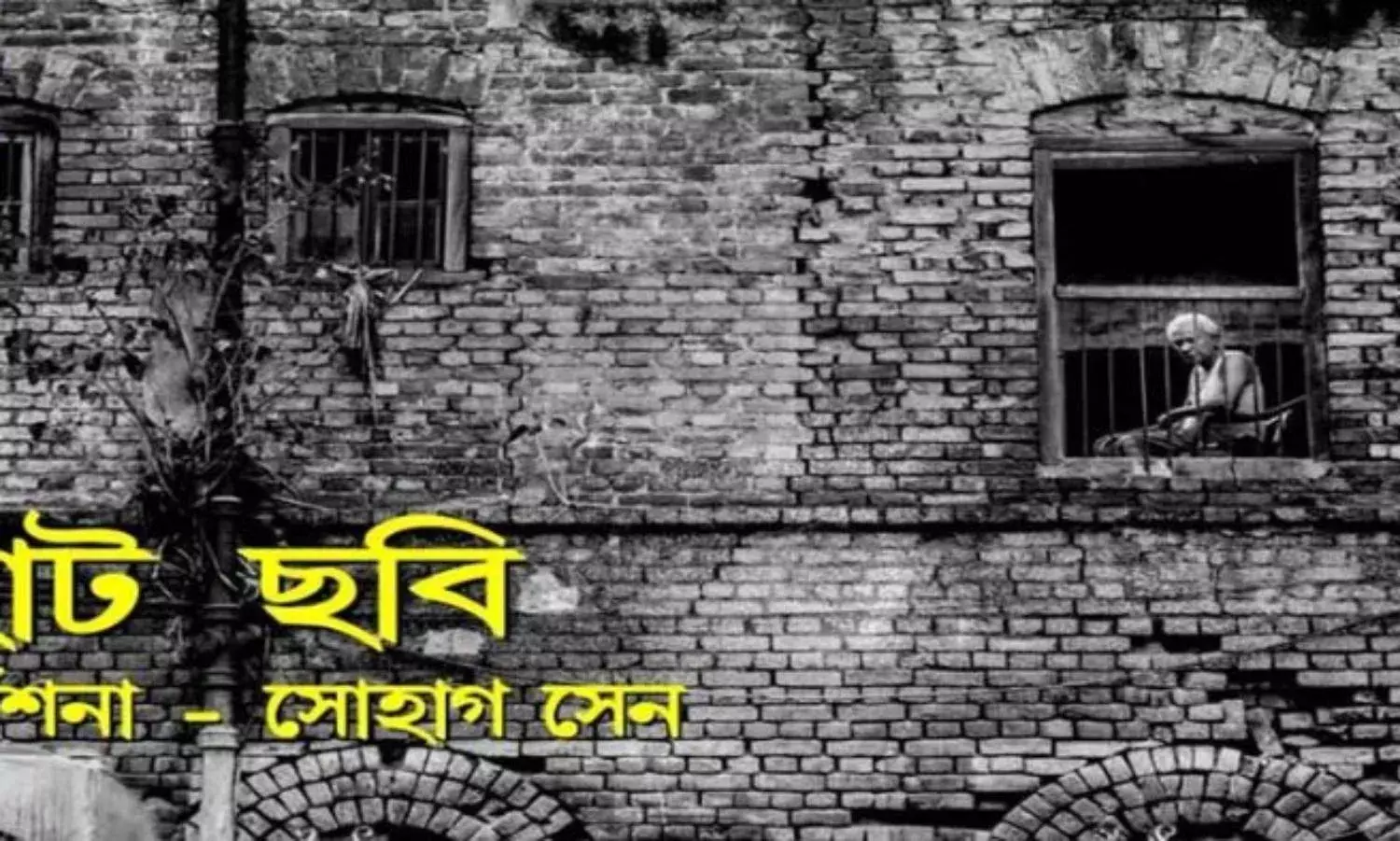

Sen recently presented her new play, Chhoto Chhobi (The Small Picture) at the Gyan Manch with her group of wonderful actors, all with a long track record in theatre.

Chhoto Chhobi is an experiment in the form of theatre where cinema intercuts into the play being performed, as though it is being shot with short stories (chhoto chhobi), each independent of the main play.

The play opens with a film crew trying to put together the day’s shooting schedule, with the usual cacophony and chaos and nerves-on-edge that form part of a film shooting. The director is a very young man trying his best to explain a given scene to the actors on one hand, and also very anxious about approval by the new producer who also wants to play a role in the film.

We have often encountered a play within a film, but a film being shot within a play is not a common experience. It takes time for the audience to warm up to this situation, but the sterling performance of the actors partly sets our doubts at rest.

The characters that form the main play, who are also the film crew, are fleshed out very well, each one different from the others. The director Rahul (Writtwik Mukherjee) however, does not quite fit into the directorial chair because he appears too young and gangly and rather raw.

His chief assistant, a young lady who has a soft corner for him which he does not care about, has an attitude problem.

Disha, the scriptwriter shuns all Rahul’s advances who loves her though she is a single mother and much older than he is.

The cinematographer (Ayan Mukherjee) keeps panning the camera on or not on track, and somehow the shooting seems unreal for it doesn’t quite lend itself to the ambience of the proscenium. The long, single-shot takes appear forced as films do not usually shoot in this manner.

Between the shooting of each episode – there are two being shot and the second shows an entire film, commissioned as a series for the director – there is ample interaction between and among the crew members, who are also friends or not quite friends in real life off the floors. These scenes are dynamic and lively and entertaining, though a few have an underlining of pathos.

The two plays are performed a bit theatrically but the acting is still very good, particularly in the first. The stories however, are quite predictable. The first is probably inspired by Nachiketa’s famous song ‘Vriddhasram’, focussed on the interaction between an aging mother and her adult son who has come to leave her in an old age home.

The second play also talks about an aged father, waiting for his Paris-based son at the airport, and before the shoot-within-the-play is half over, you know that the son will never come.

Why two ‘films’ on the same theme, of the neglect of parents by NRI adult children?

The third in the series actually projects an entire film already shot and edited. This has a better story because it cuts into the real life love story of Disha, the scriptwriter whose lover Mansoor Ali left her behind to make a glorious career for himself in films in Mumbai, and never came back.

In the film the two have a happy reunion, beautifully enacted by Koushik Basu and Sutapa Ghosh. But in real life, after they have watched the film, Disha resists all Ali’s attempts to be back together and live happily. This is a good touch that points out how real life is very different from what a film shows and narrates.

The third is the best of the three ‘films’ but again, it loses in terms of technical quality: the film is amateurish and badly made. It is unclear whether director Sohag Sen does this deliberately to reflect the young director’s inability to put it across.

The songs are sung beautifully by all the actors and the dances are also graceful in their execution. This underscores the detailing of the music track. The set design and props are good and fit in too.

But Sen must remember not to extend the performance beyond the proscenium, as she has tried to do in this play. Some actors interact with some characters seated in the audience and sometimes, the interaction takes place in front of the stage. People sitting at the back will not be able to see these portions at all. It is an unusual experiment that does not work in a relatively large auditorium.

The acting cast is brilliant and that is an understatement. Soma Mukherjee, who portrays the mother in the first film with her starry airs and suddenly becomes coy and flirtatious once the shoot is over and the producer makes his entrance, is superb in every scene. Sunayan Khotel as the son is convincingly awkward and a bit nervous as he finds it difficult to tell his mother that she will have to live here from now on.

Sujoy Prosad Chatterjee as Anil Sharma, the arrogant, non-Bengali producer who often butts in and imposes a change in the story, is very natural and convincing, though in terms of theatrical experience he is almost a fresher. Madhumita as the hairdresser, Rajib Mukherjee as the boy who takes the waiting father from the airport to his home, and Sulagna Choudhuri as the assistant director who finally gives up on the director, are totally committed to their performance.

The literary device of stories within a story is thought to date back to a device known as a ‘frame story’, where supplemental stories are used to help tell the main story. Typically, the outer story or ‘frame’ does not contain much matter, and the bulk of the work consists of one or more self-contained stories told by one or more storytellers.

But in Chhoto Chhobi there is no narrator. These are films being shot and some of the cast in the main play are actors in the films being shot. It is a courageous attempt to go beyond the routine, but in this case it does not seem to work.

According to Sohag Sen “Chhoto Chhobi is based on on the premise that the new short is the next sweet. Worldwide, shorts are being treated as new age because the films ensure limited concentration and of course aesthetic stability. The play somewhere reinforces that relationships too have a shorter span and art in no exception.”

As Chhoto Chhobi is fluid and loosely structured, the film episodes lend themselves to being replaced with different issues, to add to the richness and versatility of the play.