The Calcutta Sonata: A Brilliant Tribute To The Piano

The cultural space that the piano created for itself within Calcutta

The piano is a heritage that the British probably left behind in India in general and in Calcutta in particular. The piano was considered to be a clear sign of aristocracy and affluence in the city because it was associated with a rather Westernised group of people who belonged to different cultural groups such as Anglo-Indians, Parsees, some Britons who did not go back and Bengalis.

The piano was extremely expensive but then Prime Minister’s Perestroika in the 1990s brought down the price of pianos to an affordable level and within the reach of the middle class. The admission to piano tuition at the more than 100-year-old Calcutta School of Music increased and pianos taking on rentals of Rs.1000/month also rose.

However, few Indians really identify with the piano as a cultural symbol in India because no one has studied it as such. One noticeable association with the piano has historically once been associated with Hindi and Indian films. The piano has almost been a constant presence in Hindi films during the 1940s right upto the 1970s crossing from Black-and-White to Colour and one wonders why it faded away with time. The piano was not a decoration but played an important role not only signifying class and sophistication and aristocracy but also a dramatic role especially between lovers – confused, estranged, in love, and so on which added to the drama of the film and offered scope for grandeur within the film.

Music directors of those times were also experts in playing the piano and reading notations which encouraged them to introduce the piano into the film. Birthdays, engagements, wedding receptions were sometimes inserted into the narrative to make space for a music scene with the piano sometimes enriched with a dance performance. Even in a very middle class milieu, Bimal Roy used the piano in a birthday party song in Sujata that extended beyond the song number to explore the tragedy of a girl who does not know when her birthday falls.

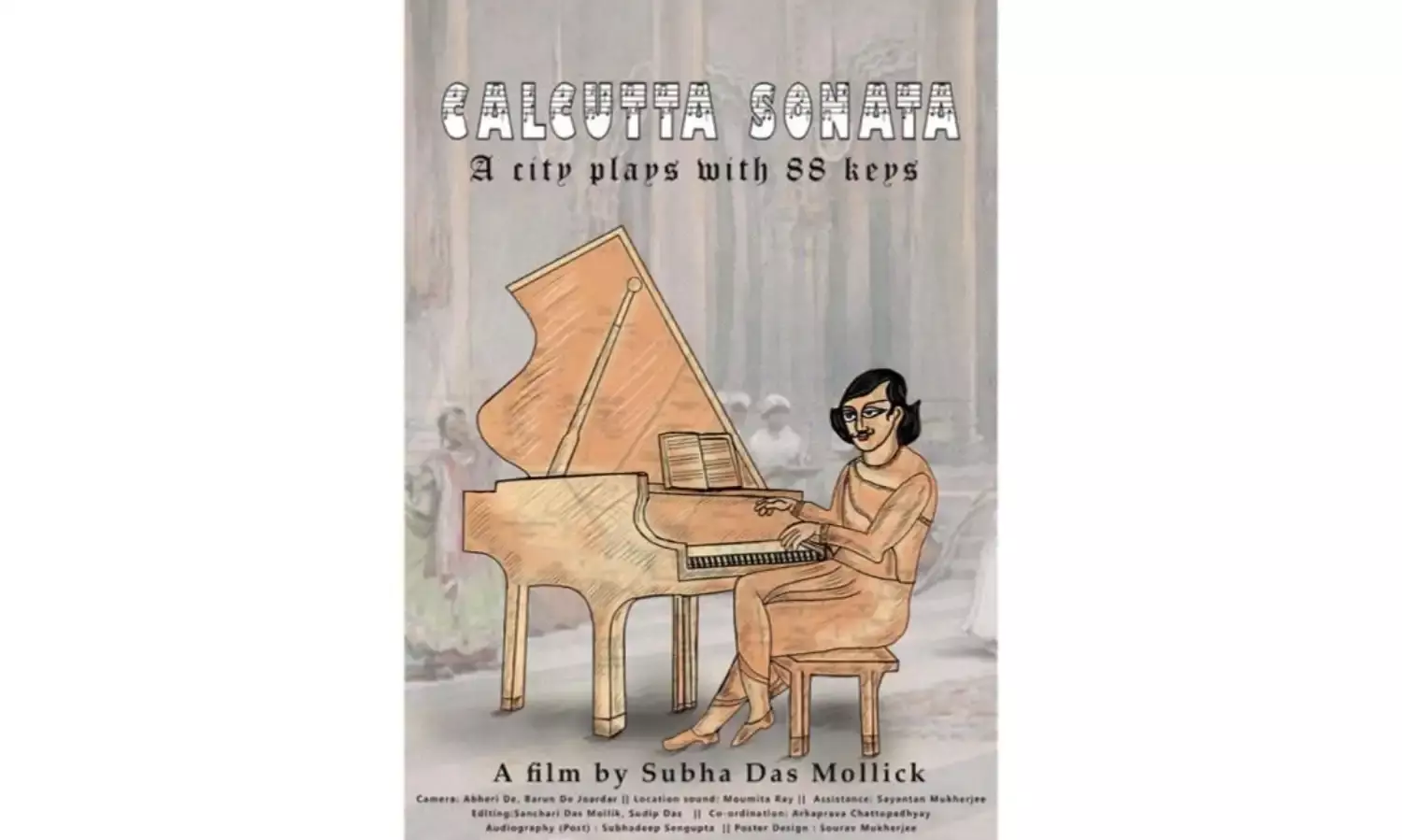

But over time, the scenario and landscape of the Hindi cinema changed with smaller spaces for the living room and storylines making space for middle-class and working characters whose images and the story would not go with the piano. In this deserted landscape, Subha Das Mollick has made a startling documentary film called Calcutta Sonata that traces the history, the culture and the sociography of the piano within the city limits of Kolkata though she has used the original name of the city.

Subha Das Mollick is a name and face with a crop of thick, wavy hair filled more with salt than with pepper is familiar among documentary filmmakers, media and communication students across Kolkata. She is a media teacher who has made more than 50 documentary films on a variety of subjects, most of which have been aired on the national television.

Calcutta Sonata explores the cultural space that the piano created for itself within Calcutta at one time and how it evolved into an institution unto itself is what the film defines, describes and elaborates on. So far the film has won two prizes - Satyajit Ray Silver Award at the 1st South Asian Short Film Festival and Best Documentary Film at Hyderabad Bengali Film Festival.

“I conceived the idea when I was attending a video conference between Cambridge scholars and ourselves at iLEAD. The topic was 400 years of India Britain relationship. Railways, telegraph, education system and cultural influences were discussed. Listening to these discussions I got the idea that piano has had a far reaching influence on the music scene in India. This was 2014,” says Subha.

(Fauzia Mariker shares an anecdote with the Calcutta Sonata team)

Over the one-hour running time of the fim, she has covered more than 200 years of the historical evolution and positioning of the piano journeying to places, churches and homes of pianists, piano teachers and those who reconstruct old and damaged pianos to bring them to functional form. One gets to learn many things about the piano and its performers and masters who map out the different genres of music from Western classical to Indian classical recitals and scholarly comments.

The pianos featured in the film are: The oldest one is a Erard Square Grand piano; the big piano in Calcutta School of Music is Bosendorfer; The Great Eastern Hotel piano is M.F Rachals, the one at Dolna Day School is Julius Feurich. Some of them played modern Yamaha pianos. There is one Steinway piano also. The way Mr Braganza’s men put together that antique piano which had turned into rubble has to be seen to be believed. How Indian songs can be played beautifully on the piano is also an experience.

The film has been extensively shot across Kolkata in churches (St. John and Christ Church), schools, people's homes, Marble Palace, Calcutta School of Music, Victoria Memorial, Rabindra Bharati Society, Trincas, Great Eastern Hotel and of course the streets of Calcutta. It does not drag its feet even for a second over its hour-long footage though the subject is somewhat distanced from generation NOW who are not too used to digital music and recorded music to be able to appreciate the classicity of the piano.

(At the Braganzas workshop on Marquis Street)

“Just as there was a lot of western influence on the architecture of the zamindars' homes in North Calcutta, the same way piano brought a lot of western influence on Indian music. Just as the Indians led a very Indian lifestyle inside the homes with Gothic and Corinthian pillars, same way, the Indians (Bengalis) adapted the piano and made it their own,” Subha elaborates at length.

“For me, it has been a learning experience all the way. I got to know Kolkata much more intimately. In retrospect I realize that the story of piano in Calcutta has a unique angle - and that is, the Bengalis, starting with Jyotirindranath Tagore who adapted the piano to Indian music. This was taken to a culminating point by V. Balsara. This legacy is being continued by Sourendro Mullik. That way, the piano's story in Calcutta is unique. I guess the reason behind this is the Bengal Renaissance,” she explains.

Masters, experts and scholars who have contribute to the film in a significant way are - Devajit Bandyopadhyay: Music scholar, expert on Bengali theatre songs, has written a book on Jyotirindranath and his musical compositions; Fauzia Mariker, a piano who was Principal of Calcutta School of Music for a brief period, Sourendro Mullik: Pianist, descendants of the Mulliks of Marble Palace. He specializes in Indian piano recitals, Jyotishka Dasgupta: Presently Principal of Calcutta School of Music who is also in charge of conducting the Trinity College music exams, Sarvani Gooptu who has done her PhD on Dwijendralal's songs and literature; presently in charge of the research wing at Netaji Open University, Sarvananda Chowdhury: Prof. of Bengali, singer, music scholar; specialist in Vivekananda's music and Sourendro Mohan Tagore's music, Subhadeep Sengupta: National award winning Audiographer, Deepak and Shashi Puri who own The Trincas and Mrs Puri is an accomplished pianist herself, Debabrata Mitra: Jazz Pianist, who has accompanied Pam Crain's performances on stage, fusion pianist Abhijit Patranobis, Tony Braganza, proprietor of the legendary Braganzas in repairing, tuning, reconstructing and resurrecting pianos of all makes, Rakesh Mitra, Manager, Great Eastern Hotel and Indrani Ghosh: Retd. Curator, Rabindra Bharati Museum.

(An old piano being put back to shape at the Braganzas workshop)

But Subha’s research into the piano in Kolkata is ongoing as she continues her quest to discover the presence of the piano in antique paintings to pin-point its historical and cultural significance which began with the film but did not end with it. “While preparing a write up for World Music Day, I stumbled upon this late Mughal painting made sometime between 1830 and 1840. The painting shows an upright piano in the Ghusal khana or hamam of Red Fort.

The caption below the painting says, "here the Mughal emperors held their most intimate musical gatherings." Says Subha, going on to add, “This painting was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of New York in 1994, through the Louis E and Theresa S Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art” which is an excellent comment on the piano being a completely apolitical and secular instrument that can be used to create and sustain harmony just as the instrument with its music does.