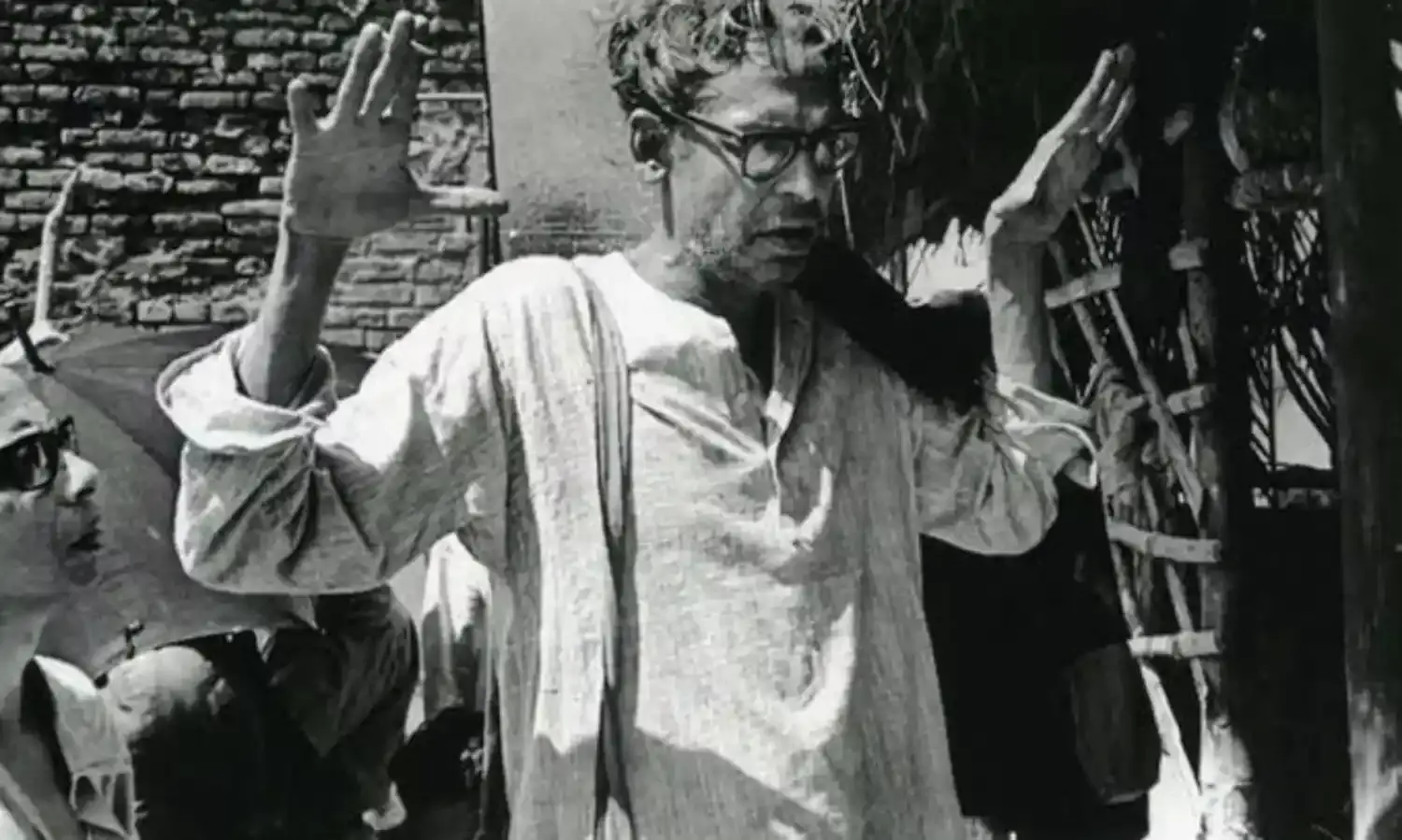

BJP Drags Ritwik Ghatak Into Citizenship Controversy, Family Furious

BJP Drags Ritwik Ghatak Into Citizenship Controversy, Family Furious

Two things are happening simultaneously in Kolkata, India and Rajshahi, Bangladesh both of which are very destructive of the archival heritage filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak built carefully through his films many years ago.

The first is the active resistance by three noted film societies in Rajshahi, Bangladesh to the demolition of Ghatak’s ancestral house in Dhaka.

The second and very caustic one is the use of unauthorised misuse, abuse of selected clips from Ghatak’s films in a video by the Youth Wing of the BJP to further their promotion of the Citizenship Amendment Act. Let us take a closer look at these one by one.

Ritwik Kumar Ghatak was born on November 4, 1925 at Jindabazar in Dhaka. He and his twin sister Prateeti, were the youngest of nine children. The other children were – Manish, Sudhish, Tapati, Sampreeti, Brototi, Ashish Chandra and Lokesh Chandra. His father, Rai Bahadur Suresh Chandra Ghatak was a Deputy Magistrate. Their lifestyle was a fusion of the West and the East. Ritwik’s niece, Mahasweta Devi, noted author and activist for tribal communities in West Bengal and Bihar recalls how she, Bhaba (Ritwik) and Bhabi (Ritwik’s twin sister), would form a small group by themselves. The child Ritwik grew within the warmth of Nature. But he spent a large part of his childhood and adolescence in Rajshahi’s Miapara neighbourhood.

Understandably, three leading film societies in Rajshahi and film activists in Dhaka have raised their strong voice against the demolition of a home that was already partly demolished in the past and are pleading to the powers-that-be to turn it into a heritage site and turn it into a Ritwik Memorial. The three film societies are – the Rajshahi Film Society, the Ritwik Film Society and the Rajshahi University Film Society. The three societies came together in to create a human chain on December 24 as an expression of their protest. The activists in Dhaka will do the same on Saturday, the 28th of December.

Hussain Mohammed Ershad, President of Bangladesh (1983 – 1990) is said to have leased the ancestral house of the Ghatak family to the Rajshahi Homeopathic Medical College at a throwaway price. They are now using the entire house including the rooms in which the members of the Ghatak family lived.

Ghatak was very close to this family home and once he also invited the litterateur Sarat Chandra Chattopadhay to preside over a literary discussion. He also edited a literary magazine called Obhidhara when he lived here.

A few days back, the Homeopathic Medical College began to break one portion of the same house and construct a cycle garage there some time before this. Thirteen cultural organizations in Rajshahi rose up against this demolition and stood together to form a protest human chain (Manab Bandhan) on the 24th. They have also appealed to the District Magistrate to stop the demolition with immediate effect. Among the protestors were artists, litterateurs and noted filmmakers like Naseer Yusuf Bacchu, Tanvir Mokammel and a dozen others. They also placed a demand to preserve it and convert it to a museum dedicated to Ghatak and his films.

Imagine a Hindu Rightist political organization like the youth wing of the BJP unauthorizedly using (misusing) selected clips from some of his eminent films within a video they are making to promote their support of the Citizenship Act! The clips they had planned to choose were from Megha Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha (1962).

The six-minute clip it was proposed, would be shown as part of the party’s awareness campaign in West Bengal. One West Bengal BJP worker has been quoted as saying “artists like Ghatak did not follow any party line and analyzed socio-economic situations in their own independent way.”

This is wrong. Alternative cinema in the third world country has consistently battled to represent imperialism, hunger and the slavery involved therein and Ghatak is the best example within Indian cinema in general and Bengali cinema in particular.

True, that the pain of having to leave his roots and built new roots here in India remained with him till he passed away. But that in no way shows that his films that reflect his pain could back any argument for the Citizenship Act which has nothing whatsoever to do with his entire volume of work including the trilogy they have chosen.

The refugee has no caste or communal identity because being a refugee is itself an identity of a forcibly displaced, disgraced, homeless person who has no country and no home. “A revolution in the arts does not erupt out of the blue. It is through a different chemistry altogether that one genre of class art grows out of another genre of class art.

One can find a consummation only by studying the past, absorbing its best elements into one’s heritage, and then bringing one’s vision to bear upon it. There is no other way to reach consummation. All other ways I find puerile, stupid and sick. There was a time when people forgot this and from out of such an attitude they proclaimed that Rabindranath Tagore was a poet of feudalism, of semi-colonial, religious mysticism, and hence of no account,” was Ritwik Ghatak’s comment on cinema as a form of revolutionary art.

Says Kumar Shahani, one of his most renowned students at the FTII, “the impetus, not only to the obvious narrative content of his films, but to their very language, was given by the tremendous splintering of the social system, of its values, while a facade of a hoary culture was still being maintained. The contradictions of a society that could have modernized itself after attaining formal independence are the prime causes of a deeper division.”

“Refugee?” Ghatak asks again and again in his films. “Who is not a refugee?” This forms the crux of a full-length feature film called Ekti Nadir Naam directed by FTII alumnus Anup Singh. The film sets out to find answers to this question Ghatak posed in and through his films, in a myriad different ways, mostly angry, often restless, reflecting the state of his schizophrenic mind, forever vacillating between his roots – Bangladesh, and the city that was the base of his uprooted identity – Calcutta. “Although a contemporary of Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, Ghatak’s films earned international attention posthumously as arguably the most relevant and moving cinema of our time,” says Singh.

But the family members and relatives of Ghatak, some of who are intensely involved in cinema and literature, are very angry about this gross misuse of the director’s film clips for a video that proposes to promote just the opposite ideology of turning the entire country into a Hindu Rashtra.

Ghatak identified with the characters in his films, expressed his agony of having had to become a refugee against his will. Each character could be taken as his alter-ego and being a secular Leftist, how could his films be ever linked to the party that has virtually bid goodbye to secularism, is interested in putting all intellectuals behind bars in a country that insists that it is still a “democracy”?

The first strong objection in the form of a letter from Ghatak’s twin sister Pratiti Devi from Dhaka countersigned by 23 other members of his extended family. “We want the clips from his films to be removed from any campaign on NRC or CAA” says actor-director Parambrata Chattopadhyay whose roots are in the Ghatak family as his mother, the late film journalist Sunetra Ghatak, was Ghatak’s niece. In the letter, at one place, the signatories states that they are strongly against the use of any part of his filmography divorced from its contexgt to justify laws that will make every citizen of the country pass through an ordeal to re-establish their citizenship and to render millions from a given community, stateless.

How can any party, political or otherwise, use clips from the films of any given filmmaker, without getting due permission from the ones who now own the copyright of the same? How can any political party pick and choose selected clips and use them out of context which may change the entire interpretation and meaning of the scene when watched within the context in which it was scripted? How can the majority party in Parliament indulge in this illegal manner of simply “lifting” random clips without legal and official backing?

Maitreesh Ghatak, grandson of Ghatak’s eldest brother, noted poet Manish Ghatak, reinforces the information that Ghatak was a Leftist right through his life. “Whatever one’s political views, if one has to at all use cultural figures like Ghatak or their works, they must be in inclusive causes and not in divisive ones like NRC and CAA. Ghatak stood for the disenfranchised and marginalized.”

The reason for Ghatak’s growing critical acclaim and recognition is the courage, power and anger with which he dramatized modern questions of ‘nationality’, ‘borders’ and ‘exile.’ Though a tragic victim of the 1947 Partition, Ghatak brought a positive and celebrative insight into both the personal and national dimensions of homelessness as reiterated constantly in his cinema. “Exile and homelessness can teach us the joy of living internally as well as externally without boundaries and without borders,” said Ghatak. Singh’s film unfolds Ghatak’s rare fluidity of being able to slip through all boundaries made lucid with every film, with the music in them.