Echo From Pukpui Skies: Documentary Uncovers Unknown Mizo History

Joshy Joseph's documentary uncovers an unknown history of the Mizos

Meet Joshy Joseph. He is a documentary filmmaker who has bagged National Awards for almost every film he has made over the past few decades. Over his years as a documentary filmmaker, he had redefined the term “documentary” by liberating it from the confines of a straitjacketed role to push the envelope with novel subjects, themes, storylines and treatment and that marks his distinctive identity as a committed filmmaker par excellence. You just cannot box his film into any genre within the documentary or even within docu-fiction.

Joshy Joseph has, as a maker of unique documentaries, consistently extended and blurred the boundaries that separate factual record from creative filmmaking, until these demarcations no longer serve any useful purpose. Joseph is concerned with the unfixed nature of our globalised world, but his approach reaches beyond mere themes and he often places the human character/characters as part of the environment to which he belongs. An ideal example is A Poet, A City, and A Footballer, and he leaves us to draw our own conclusions.

His latest film Echo from Pukpui Skies is not only an experiment in both form and content but more importantly, uncovers a part of history that has never found a place in history books. He has blended this narrative with the poetry of Dunya Mikhail, an Iraqi Poet later migrated to US. She was persecuted by Saddam Hussain during his regime and also by the Censor department for her very layered poetry. ‘Diary of a Wave Outside the Sea’ is an unusual autobiography in verses. She writes in Arabic and the book carries both Arabic and English Poems. The voice-over is mainly in Malayalam done by the director himself while the translations are expressed in graphics across the screen. The unique blending of poetry by a rebel Iraqi poet translated in Malayalam and English visualizing the history of the people of Mizoram we did not know gives the film a transnational identity.

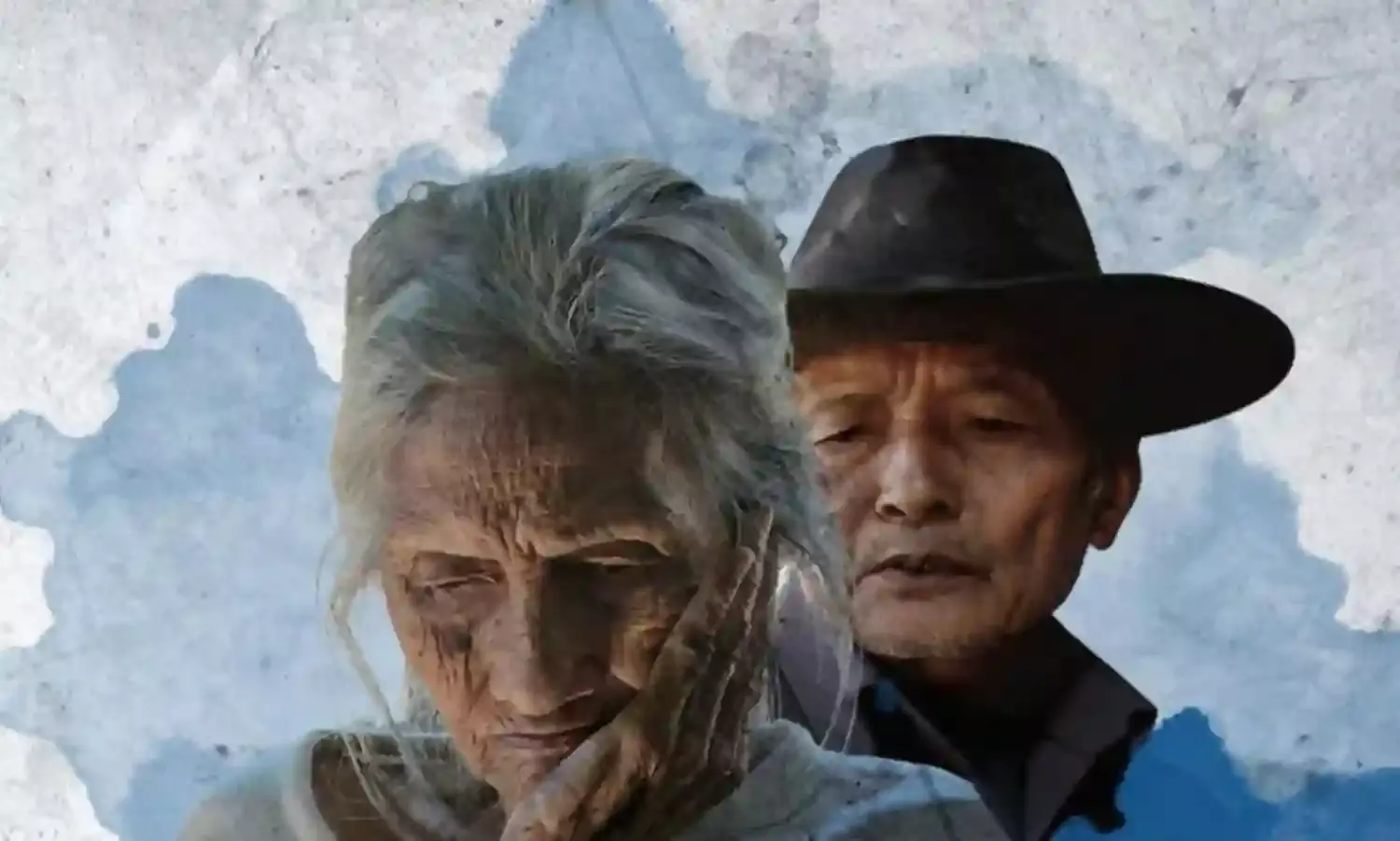

Explaining what led him to the unique and little-known history of the Mizos, he says, “I was amused to begin with and then I was shocked. Between 1966 and 1986, the Mizo people stopped writing anything – be they letters, documents, diaries or any creative form of written expression. These 20 years define the most turbulent period in Mizo history. There was an internal war between the Mizo National Front under the leadership of Laldenga and the Government of India. The villages were under Army Surveillance which they termed as ‘Grouping’ of villages. The written words were suspected of being coded messages and this unusual decision of Mizo people ‘not to write’ triggered me to imagine their inner worlds.”

The desire to use Mikhail’s poetry came from the fact that “Mikhail had also experienced almost two decades of conflict and war at Iraq and her book is simply spilling over with images. So, I decided to imagine, expand and articulate the twenty years of silence, obviously a poetic license taken by a film-maker through the lines written in a completely different situation altogether. Conflict and War test humanity on a bed of arrows which is a universal experience to relate to,” he elucidates.

On the strange combination of placing the lines of the poetry in English right on the screen instead of subtitles, with the voice of the anchor (Joshy himself) recites the lines of the poem in Malayalam, Joshy says, “The lines of the poem appear on screen as they appear in Dunya’s book. We recreated these lines in Malayalam and juxtaposed the text in English on the visual by reciting the same in Malayalam. I agree that this makes the viewing a little heavier as a lot of images in my film and the written images in the poetry overlap the visual images. One feels very crowded with this technique. So, I don’t expect my viewers to remember everything they read on screen. I expect them to cherish only what stays naturally with them. I want the viewer to see the film and read the lines too as it is a re-visit of the lack of the written words in the twenty years of history of Mizo people.”

The Holy Cross is used as a leit-motif in the film as the protagonist, once an underground activist, claims that their fight through guns was a fight against their oppressors and had a spiritual dimension to it. Adds Joseph, “Prince of Peace – The presence of Christ, in their daily lives makes one wonder as you travel through Mizoram today, which doesn’t show any trace of these twenty years of violence at all!”

Why did he choose such a strange and enigmatic title for his film? Joshy says, “Pukpui is a name of the village where Laldenga lived and worked. This village bore the brunt most directly. So, as I revisited the memories of this old man, who was himself an underground activist, I used the ‘Drone Camera’ and looked down from the skies at his movements as if alluding to the attack from skies. A perspective is brought, and the Drone Camera footage goes beyond beautification.” Joshy has used a lot of archival footage of the past when the revolt actually happened – stopping of communication of all kinds was a peaceful rebellion but the silence was also quite explosive.

Joshy says, “The archival footage is used where you see the actual war and surrender of MNF cadres. These were procured from the MNF Video Archives. They are real cadres and real weapons used in a narrative of imagined articulation of silence by the one who recited the poems which, I did myself as my mother tongue is Malayalam and I also wanted to leave some part of my physical self in the film.”

Joshy’s continued interest in the North East stems from an unique programme. He says, “As part of a new outreach programme, Films Division started conducting film-making Workshops in North-East from 2014. In all these workshops, two films are made by the workshop debut directors with the guidance of mentors from Films Division. The participants tell a lot of stories during these sessions and I collect some of the unrealized themes from these story-telling sessions. They make two films and I make one film along with them. Mostly, these ideas are not realized by the participants for different reasons and one can call them ‘rejected ideas’ in the workshops. I pick them up just to prove that there is nothing called ‘a bad idea’, but there are only bad films made from good ideas. It gives me a kick and enriches me to elaborate the untold stories from North-East from a complete outsider’s perspective.”