Sholay Took ‘Costume’ to Another Level Altogether

45 years of Sholay

Sholay is a brazenly open mainstream Bollywood film that makes no pretensions of being an artsy film. So, those nourished on a rich diet of Godard, or, Bergman, or, Antonioni, or Ozu may have reacted to the announcement of the film with the arrogant disdain they shared for every Bombay film – (“Bollywood” did not exist in the lexicon of Indian cinema) when Sholay was released.

But when the celluloid wonder called Sholay slowly unfolded, layer by slow layer, like the several peels of an onion, it was left to everyone from the intellectual to the illiterate, from the poor villager to the city-smart corporate guy to tilt a hat to this miracle of a film that lives on in the minds and hearts of all Indians 45 years after it was first released.

If you look closely, every single department of cinema – casting, characterization, screenplay, dialogue, cinematography, music, songs, sound design, art direction, editing, location, speech patterns and language, and even costumes were worked out in masterful detail. The film is so mesmerizing, made especially attractive because of Gabbar Singh, the most outstanding and memorable villain in the history of Indian cinema, that not many paid attention to the costume design.

Looked at closely, the costume designing of the main characters was done with as much insight and research into detail as were the other areas of film-making. “Costume design is not just about the clothes: in film, it has both a narrative and a visual mandate. Designers serve the script and the director by creating authentic characters and by using colour, texture and silhouette to provide balance within the composition of the frame. The costume designer must first know who the character is before approaching this challenge,” wrote Deborah Landis Nadoolman in “What is Costume Design?” (Screencraft: Costume Design,48.)

Sholay uses costuming among other elements to keep a line of distinction from one character to the other so that each character stands in relief and also forms a part of a comprehensive whole. The class distinctions between and among the characters, their occupations and their lifestyles were also kept in mind while conceiving and designing the costumes.

Shalini Shah did the costume designing of Sholay along with Chela Ram. But the concept and ideas belonged to the director Ramesh Sippy and perhaps the writers Salim-Javed. Do you know that a fashion house once advertised the costume Gabbar Singh wore in Sholay on their website and offered it at an approximate price of Rs.2850?

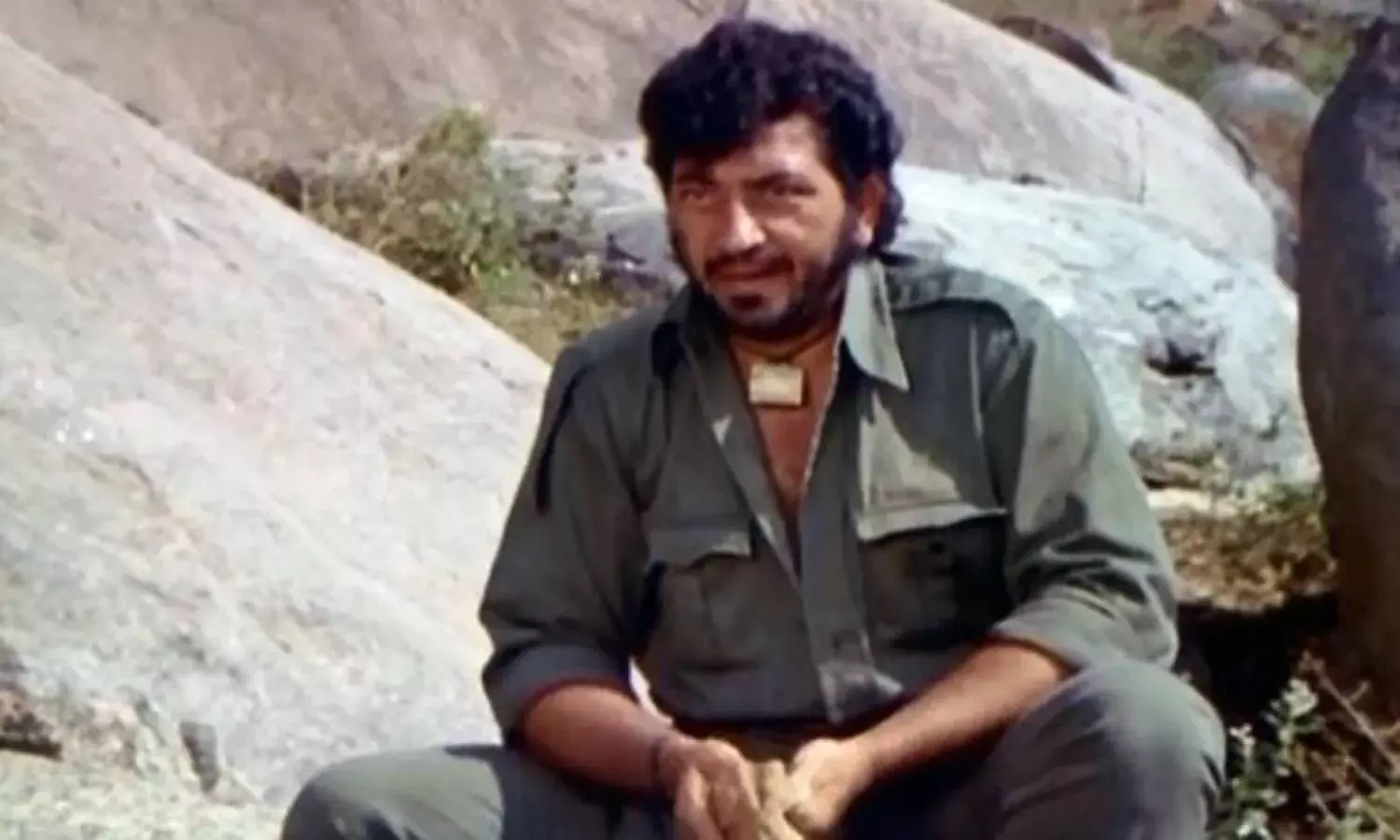

Sippy said that he wanted to replace the normal dacoit costumes in films of shirt and dhoti with olive green safari suit that would resemble military fatigues. So, Gabbar’s costume comprised of this olive-green safari suit, a metallic taveez strung on a black thread across his neck, a cartridge-lined belt he sways this way and that to threaten his men, and a small cloth bag of khaini he chews from time to time and spits out at random. His boots are smart too but covered with a layer of dust. His curly hair is unkempt and he shaves rarely.

There is a constant ugly glint in his roving eyes matched with an evil grin. The script very intelligently does not give him a back story like an abused childhood or torture in an orphanage. And this is what makes him so mesmerising to the audience. He represented pure, undiluted evil in human form. He also wields a gun for easy gunning down of his “coward” men.

Fashion Designer Shilpa Ahuja in her blog writes: “All you need to become the scariest villain of all Bollywood time is a khaki safari suit and a toy gun! And skip shaving for at least two weeks. To recreate the bullet belt, just tape up or stick a few red-paper rolls (easy) to an old brown belt.” She was suggesting this as one among the ten best party wear for men borrowed from Bollywood films.

Jacob Davis, a tailor, wanted to patent his idea of using copper rivets on denim pockets that made them last longer but he didn’t have the money. He approached Levi Strauss to buy a joint patent. The patent was granted to them on May 20 1873; and this was the birth of the denim. But it is Sholay that turned it into a fashion statement among young men in 1975, 100 years after it was invented.

Divyani Ratanpal in a tribute to Levi Srauss’s birth anniversary, (The Quint, 6th February 2020) writes: “With Sholay, Amitabh Bachchan began a social upheaval in India. In the movie, both his character, Jai and Dharmendra’s character Veeru fashioned denims.” The Sippys did not want their cast to be clichés, according to Anupama Chopra’s Sholay, Remaking of a classic which fetched her the National Award. Therefore, Ramesh Sippy decided that his two heroes would wear Ramesh Sippy wanted his heroes to wear denims, western cowboy style.

Veeru and Jai were to be denim clad city side slickers. For the shoot, Amitabh took along his favourite pair of jeans and a jean jacket covered with 60s style stickers popular at the time. The stickers were removed but the jeans stayed. Veeru wears a large buckle belt too and both of them are always in need of a haircut and a comb while Jai carries a mouth organ in his pocket.

As Sholay went on to become a roaring success, star struck men across India asked their tailors to get similar denims stitched, or coaxed their relatives to get them from abroad. This was the year 1975. The dress enhanced their carefree identity, their adventure-loving way of life and suited both of them to a tee. Jai, with his partner Veeru were dressed for the part in just one blue suit, which Jai wore all through the film - he only changed between a fitted red tee and black shirt to wear under. Today, India buys roughly 300 million pairs of jeans every year.

And what did Thakur wear pray? In the flashback, for a few scenes, he was in police uniform. By the time he calls Veeru and Jai to his dark haveli that has seen better days, he wears milk white, starched and ironed kurtas with white pyjamas. The kurta is oversized because he needed to conceal the lack of arms. He wrapped a neutral colour brownish grey shawl around him and a beautiful, silver hair-piece or, may be, touched up the front wave of his hair with silver. It not only made him look like one of the handsomest, middle-aged Thakurs in Bollywood cinema but also added dignity to his personality.

The heavy soled shoes fitted with nails are revealed only in the climax. And of course, do not forget that dainty moustache. It helped Sanjeev Kumar build up and sustain the body language the character demanded also offering a dramatic contrast with the personality of Gabbar Singh on the one hand and the two small-time goons on the other.

Who can think of anyone other than Hema Malini as the very talkative Basanti in Sholay? Basanti is beautiful. She has a mishmash sense of the ethnic so wears lots of flowers in her hair, ethnic jewellery – jhumkas, a nose stud, two chains and lots of bangles, colourful and printed sets of ghaghra, choli and a dupatta draped like the anchal of a sari. Her forehead has a small bindi but that is about all. She has curly hair which she fastens with a bunch of flowers which hang across one shoulder.

This defines the very colourful, free and bold personality of a pretty young woman who is not afraid either of carrying young men back and forth from the station to Ramgarh or of shouting at Dhanno to save her ijjat when Gabbar’s men on horseback chase her through the fields. Basanti may be a “Gaon Ki Gori” but with a difference. She is neither coy nor shy not shrivels up in the presence of males and is stripped of any nakhras.

Radha offers a striking contrast to Basanti and she has two different images linked to two phases of her life over two different times. In flashback, she is a very young girl running around with the Holi thali in her hand, lots of colour on her face, applying the colours to whoever she meets and talking twenty to the dozen.

She wears a colourful ghagra- choli outfit but there is so much colour in her body, her talk and her performance that you do not quite recall what she was wearing. When Veeru and Jai meet her, she is a young widow who hardly utters a word, never smiles and is draped in a stark white sari with a white blouse with her hair covered slightly with the end of the sari.

This establishes the distinction, both in terms of class and status, the distinction between the placing of these two young women – Basanti and Radha and also in the difference between Radha in the flashback and Radha in the present time. Every other cameo character’s identity in the film is underscored by the costume he/she wears.

The characters of Soorma Bhopali or the jailor who is from “angrez ke zamaane” or, the funny Mausi who as an affectionate widow, Helen as the barely clad in shimmering costumed dancer are detailed with great care and you remember every character along with his/her bearing, body language, the cadence in speech patterns and the costume.

The last word belongs to David Robinson (“The Costume of Silent Comedy”, Screencraft: Costume Design. Burlington, MA: Focal, 2003. 94-109) who says, ““Actors wear clothes that identify their roles – by period, ethnicity, nationality, class, or character.” One wonders whether the characters of Sholay would have crossed all barriers of time and place and person if its makers had not paid such acute attention to their costumes.