Drawing Copy- A Lockdown Film

Platforms are flushed with lockdown films

Filmmakers in West Bengal, like in the rest of the country, are deeply frustrated by the sudden lockdown in their lives and lifestyles. So, in a way to rid themselves of depression on the one hand and challenge their creative powers on the other, many are making short films within the interiors of their homes. To catch the outer world, they are sometimes repairing the terrace or using the window as a cinematographic angle.

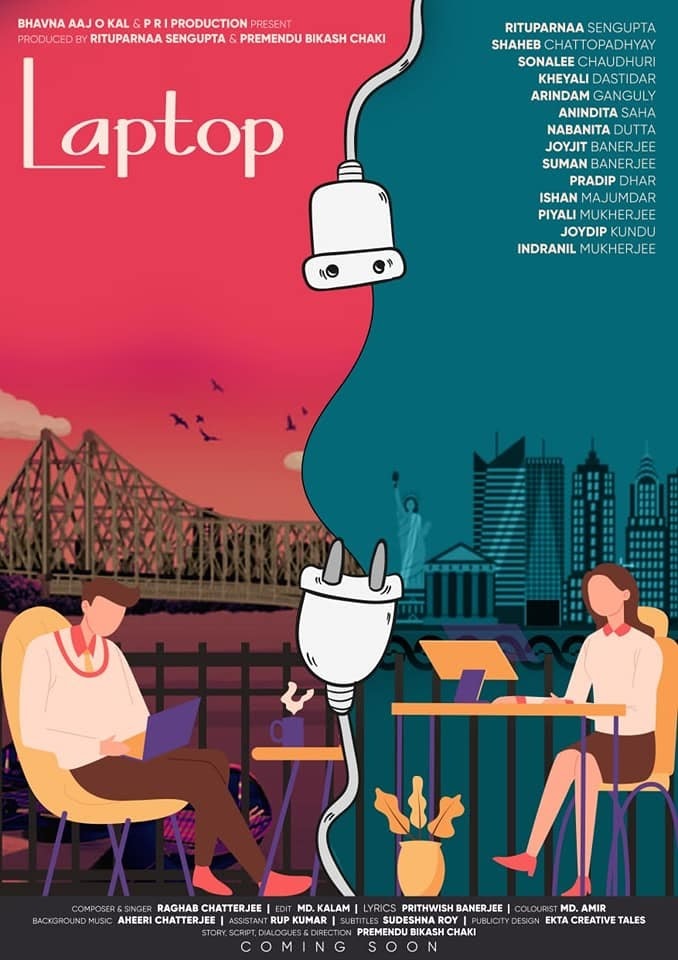

OTT platforms are flush with lockdown films, mostly limited by the constraint of space and forced often to rely on telephonic conversation between and among the characters. However, some have found innovative ways to skirt the issue of social distancing that needs the characters to remain indoors in their own spaces and communicate from there with the other characters similarly distanced. Premendu Bikash Chaki, a cinematographer-turned-director, made a lockdown film called Laptop with an impressive starcast.

The film has a positive approach towards fractured relationships that smoothen out during the lockdown. Produced and enacted by Rituparna Sengupta, it has very low-key and impressive music to get the message across. Intercut with visuals of newspaper clippings about the impact of the Corona-Virus on individual and social relationships, the film closes on a note of hope and optimism in which a husband who cannot go back to the US because of the lockdown somehow finds that his fractured marriage has mended itself. The film closes on that note of hope but one wishes it could have clipped at least around five minutes from its 26 minutes of running time.

But a better effort comes from the fresh director Kumar Chowdhury, basically an actor confined to cameos and supporting roles in Bengali movie. He is making short films on his video- camera within the four walls of his home. Among them, the one that will strike anyone and everyone who watches it, is called Drawing Copy. The film is focussed on the childish drawings of a six-year-old. The drawings, done in pencil and possibly crayons, are a microcosm of any drawing book of any six-year-old boy. The camera focuses on the flipping pages of the drawing book. One is called “Family” showing two tigers and a cub sitting together each coloured differently. Another, called “The River” is a landscape quite in keeping with how we drew landscapes as children as part of our drawing homework.

“The film is an experience from true life. It is about my nephew as a child who has now grown up. The drawings are by my son Aarko when he was six years old. The drawing copy narrates the story of my nephew’s sad childhood,” says Kumar.

There seems to be little till you reach towards the end. A drawing called “Mother” shows a lady in a salwar kameez with a grim expression. There is an older woman beside her – the boy’s grandmother as he captions it. The next drawing again is of the child’s mother. Beside the mother is a wall and the other side of the wall shows the drawing of a grown man. A little hand writes “Daddy, I Miss You” beside that drawing. Then, the hand wipes out the words and on the last page, in a childish scrawl, the boy prints out the word “Divorce”. Some one calls out and we can hear the boy shouting “Coming” and that is the end of the film.

The film does not have dialogue except the boy, off screen, responding to his mother’s call. The music is low-key, very subtle and fleshes out the tragedy of a lost childhood. “A sister got divorced and her son, affected by this, expressed himself through his drawing book. But he would never draw any picture of his father. We discovered that he hid the drawings he did of his father. This made a deep impact on me and has now come out through this film,” says Kumar. Drawing Copy is one of the most outstanding short films on divorce and its impact on children.

The stunning visuals are orchestrated beautifully, the only movement shown through the flipping of the pages of the drawing book, as we wonder what is happening. Some of the drawings, of people like the boy’s grandmother’s sister, stand out for the acute observation of life by a child. Sometimes, you feel you are watching a film without much movement. But this is the impression the director intentionally created for the viewer. There are no people in the film and so, not a single dialogue. This makes for an extremely powerful climax. The film is conceived, scripted, cinematographed and directed by Kumar Chowdhury who has named his production house after his son Aarko.