How Ebrahim Alkazi Revolutionised the Destiny of Indian Theatre

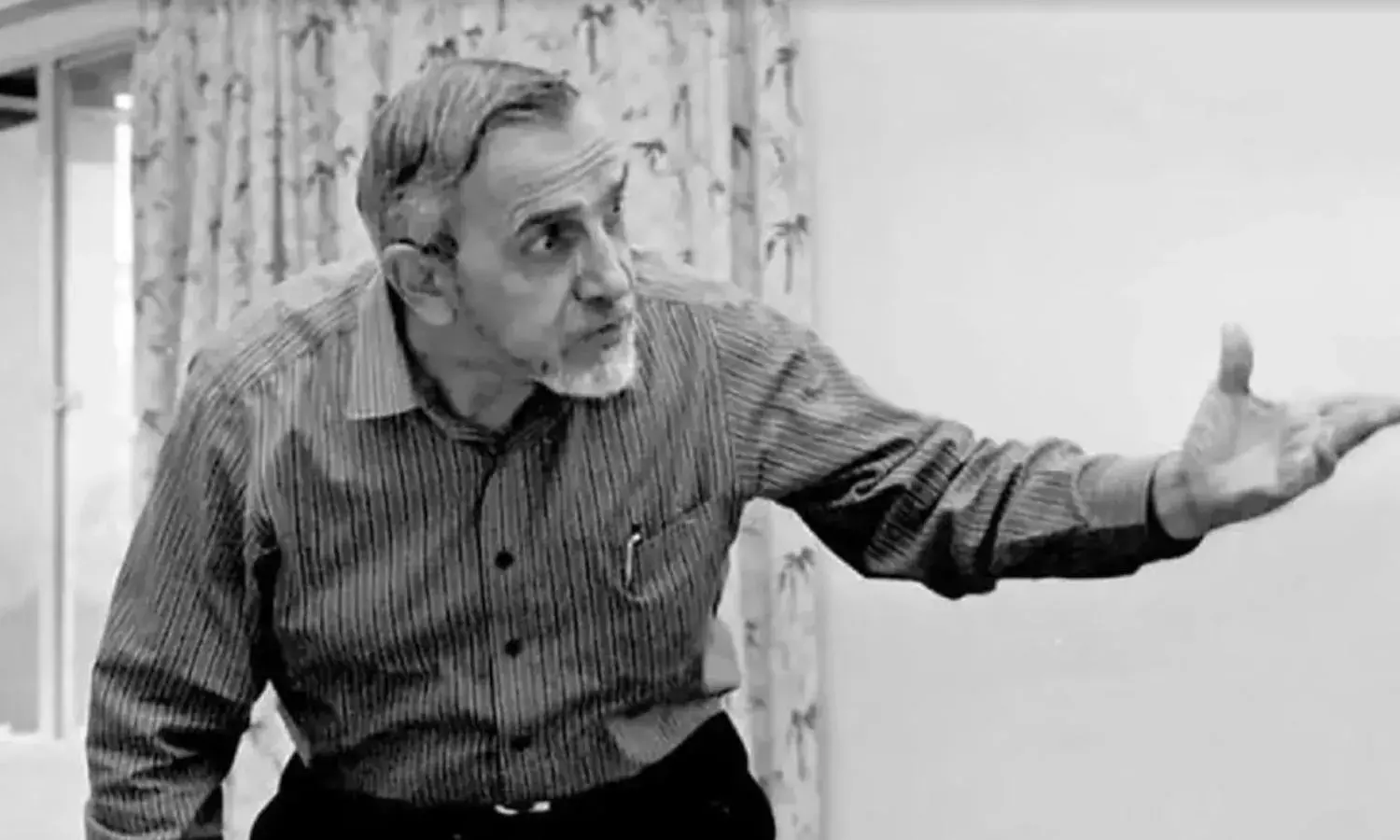

Remembering Ebrahim Alkazi (1925–2020) on what would have been his 96th birthday.

Ebrahim Alkazi once said in an interview, ‘I think that there are certain ground root elements in theatre, there is a certain set of rootedness and earthiness in the work you do, and unless your inspiration and the concept in the work of theatre starts from there, I don’t think you can create fine work. You have to create an atmosphere; you have to work within salubrious surrounding’.

As the director of National School of Drama (1962–77), Alkazi devised the vision, system and pedagogy of theatre in India. He revitalised not only NSD, but revolutionalised/channelised the destiny of Indian theatre. He was one of the nation builders, instrumental in the cultural and emotional integration of the country. He was a true cosmopolitan who had encountered the essence of different cultures and traditions, such as that of France, Germany, England, Arabia and India.

While heading NSD, one of his concerns was to make it truly ‘national’—by integrating students from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds of the country and infusing them into the fabric of a cultural unity. NSD had to represent the ‘national movement’, in its imagination, intellect, mind and emotion.

Alkazi was a teacher incomparable, as his students unanimously ascertain. He trained them in the art/craft of acting and theatre making; the ethics of being in theatre, maintaining personal hygiene, punctuality, arranging/organising the rehearsal, making tea, sweeping the stage, ironing costumes, arranging the green room and cleaning the toilets were as much an integral aspect of training, as creating a character. He imparted a spontaneous discipline and equipped his students to be professionals.

Theatre is not merely about the performance on stage and its design, it is the wholeness of the work from designing the theatre space to the atmosphere created in the auditorium. The importance of the collaborative mutuality of the group than the exposition of individual talent was greatly emphasised by him. The feeling of togetherness and harmony among actors and other artistes creates the dramatic on stage. His classes and rehearsals were as systematically organised and fine-tuned as his illustrious productions.

Alkazi did not look down on the audience nor played down to satisfy them. He endeavoured to raise the audience to a level of understanding where they could appreciate quality productions that were new and different, aesthetically refined, dense in content, poetic in the physicality of expression, purposive and meaningful. His productions were simultaneously dramatic, and subtle and precise, synchronising the technic with the aesthetic.

He was able to build an audience in Bombay (now Mumbai) and later in Delhi. An audience that included diplomats and politicians, such as Jawaharlal Nehru, bureaucrats and even purdah-clad women. He stunned and surprised them with lyrical, subdued, low-key productions of very sensitive scripts like Ashad ka ek Din, Tughlaq and Andha Yug. His productions could transcend the text, and resonate with the life and reality of the spectator living ‘here and now’, which made them popular.

The grandeur of the show, its technical excellence, professionalism, meticulously blocked scenes, perfectly delivered lines, elegant, monumental sets, and the sense of the dramatic/theatrical elements associated with stage design, costuming (done by Roshan Alkazi), make-up, etc., supplemented. Each scene was neatly visualised and wrapped; each position, movement, entry and exit, and gesture were carefully planned, rehearsed and reproduced. He triggered the visual imagination through choreography, use of lights and the sound patterns of the actors.

He could resonate the magnificent background of Feroz Shah Kotla and Purana Qila as the setting for Tughlaq as the arches, pillars, and structures suited the story. He could convincingly transcend the reminiscence of the past colliding with the present and the layered history of the same sites for the plays Andha Yug (based on Mahabharata) and Razia Sultan. In contrast, he also did productions in studio theatre, open-air theatres, converted courtyards, drawing rooms, and roof tops into theatre spaces.

Ashad ka Ek Din was presented in a small simple stage, plastered with cow dung. According to him, in an intimate space like that of a studio theatre, the performances could be experienced microscopically and the actor could be absolutely within the role, without extra histrionic exertions to stimulate emotions.

Through illustrious and pulsating productions with the repertory of NSD staged in various states in India and foreign countries like England, Italy and France, he attracted the elite as well as common people, and spawned dignity to theatre in India; made theatre popular, relevant and glamorous.

During his Bombay phase he did renditions of Greek tragedies, Shakespearean plays, and modern classics of Ibsen, Chekov, Eliot and Strindberg in English. After moving to NSD, he started working with Indian classics, Indian history and myths, and performed in Hindi (Tughlaq, Lehron Ke Rajhans, Ashad Ka Ek Din, Andha Yug, Mrichchakatikam, Razia Sultan by Shanta Gandhi and Viraasat by Mahesh Elkunchwar, etc.). The Western classics also were performed, translated into Hindi. This shift is significant.

Sanskrit plays of Kalidasa and Shudraka were translated and staged in colloquial Hindi. He often got students and faculty to translate the plays in regional languages, exposing these playwrights and vernaculars to the ‘national theatre’ scenario. One example is Adya Rangacharya’s Kelu Janamejaya (Listen Janamejaya). He started to explore the roots of Indian life and culture during this phase; quintessentially Indian theatre were performed in contemporary idiom.

He introduced Kathakali, Tamasha, Nautanki, Yoga and Bhavai along with Noh and Kabuki, into the acting training process. Much earlier, in his pre-RADA period, he had undergone rigorous training in Kathakali under Guru Mampuzha Madhava Panicker while he was acting in the play Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore, directed by Bobby Padamsee.

He was fascinated by Indian performance traditions, both classical and folk. He persuaded Govardhan Panchal to study about Kuttambalam; prompted B.V. Karanth to adapt Macbeth using Yakshagana, to produce Birnam Ban. Alkazi was happy and proud that his student Ratan Thiyam was doing productions based on Manipuri culture, traditions, movement and music; of course, one could see that Thiyam’s productions reflect Alkazi’s theatre in terms of the precision, handling of materials, colour, texture, tone, compositions, lighting, etc.

After quitting NSD in 1977, his interest returned to contemporary art as a collector and curator. He collected rare period photographs of ‘important historical moments in the interrelationships between India and England in the struggle for independence’.

Alkazi belonged to the Nehruvian era charged with optimism; he was a pragmatic, secular, sensitive, collaborative, rational, aggressive and systematic ideologue, with a dream for the nation-building. It is interesting that Tughlaq happened to be one of his major productions, which is a metaphor of the defeat of Nehruvian ideology and his concept of Nation by the people surrounding him.

Alkazi resisted mediocrity, and his continuous persuasion moulded Indian theatre and formulated its pedagogy into that we have today. Of course, Indian theatre has to move ahead of Alkazi, but we have to discern and properly recognise his dreams of Indian theatre and the legacy he has left behind.

The author is founder and artistic director of Lokadharmi Centre for Theatre Kochi, is a designer, director, dramaturg, actor, writer and translator.

This article is part of Saha Sutra on www.sahapedia.org, an open online resource of Indian arts, cultures and heritage.