Refugee Afghan Artists Try to Further their Art in India

‘This will at least keep it alive’

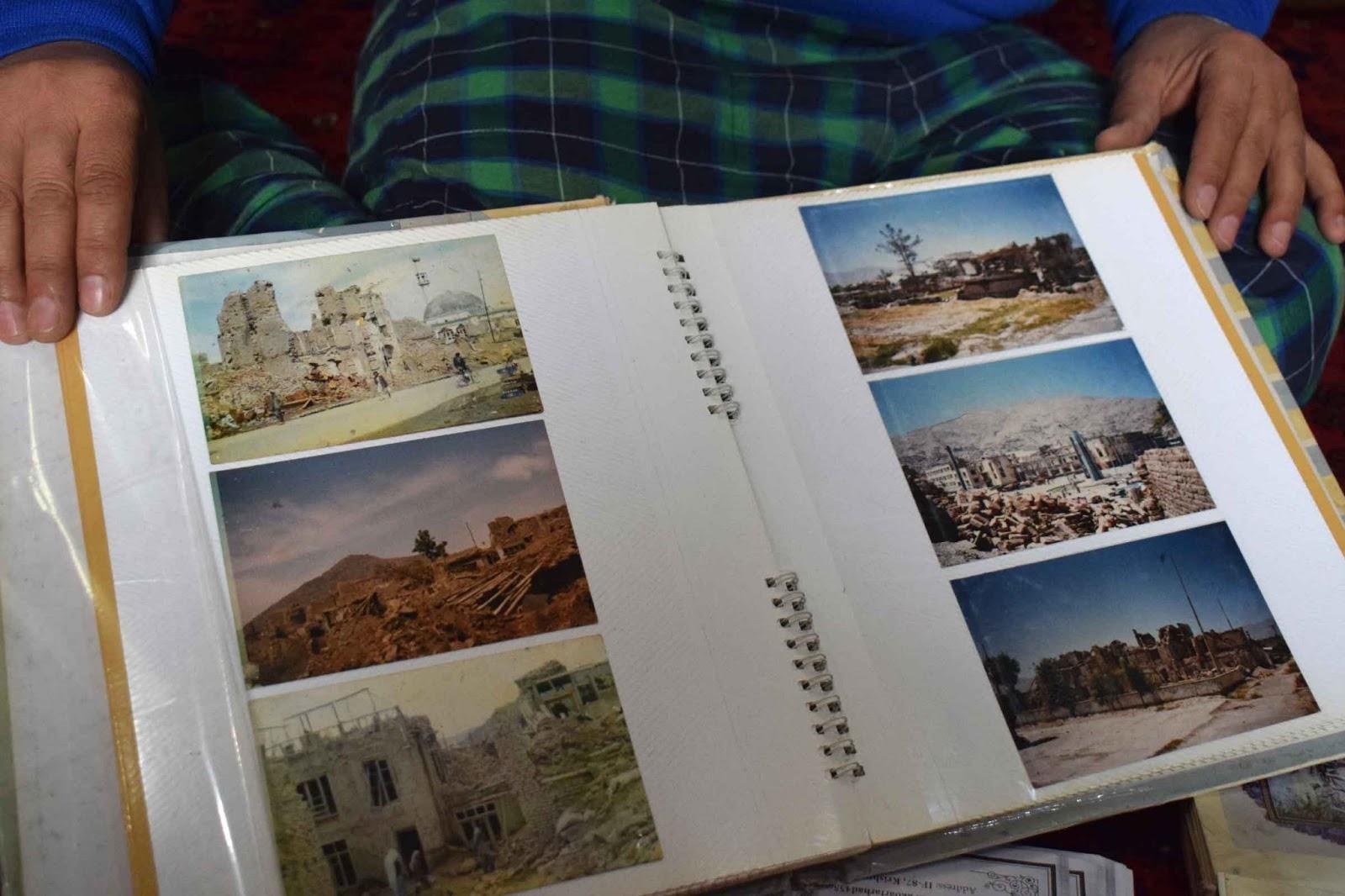

NEW DELHI: When 42 year old Akbar Farhad left Afghanistan for India along with his family in 2017, he brought along a bag full of paintings. Apart from a few heirlooms, the bag, hurriedly filled with pictures of his beloved homeland, was his prize possession.

A doctor by training, Farhad had left his profession in Kabul to pursue his art. And that made him many enemies. Radical Islamist groups in Afghanistan don’t think highly of those who do magic with the brush on canvas. They consider them ‘deviants’. Farhad was declared one too, and in a bid to save himself and his family he left Afghanistan.

Since the resurgence of the Taliban in the mid-90s several artists have been killed and many museums destroyed in the country.

“Paintings are not allowed and banned by conservative groups and violence is perpetrated against artists. I was also threatened and I felt like I could be the target, which forced me to flee,” Farhad told The Citizen.

Now in India, in memory of his bruised and cherished homeland, he looks at those pictures and tries to recreate them on canvas. They not only keep the memory of his motherland alive, but are also the source of income for Farhad and his family.

“I left my profession to concentrate on art. I like painting images of Afghanistan with oil on canvas,” he says.

The serene Afghanistan of his paintings, though, is entirely different from the one he experienced.

"It is a troubled homeland. There are bomb blasts. There is violence. There are killings. But it is the homeland, nonetheless.”

Having to leave one’s country to live in a foreign land brings no solace, but Farhad says it’s more about survival now. He struggles to sell his paintings, which are his only source of income.

“There is not much work. I don’t have any space where I can sell my paintings. Sometimes people give their orders over the phone,” he says.

More recently, he has had to paint or draw Indian landscapes, and buildings like the Taj Mahal, which are more in demand here than visions of Afghanistan. “I also make portraits, and I have started teaching art to the local students as well, but the income is meagre,” he says.

Although the tides of time and men have made Farhad a wanderer who may never return home, he hopes his children will some day have a place to call their own.

“They can’t even go to a normal school. They go to the school run by the Afghan embassy in our vicinity. I want a bright future for them.”

Farhad’s situation is similar to the thousands of Afghan refugees who are living in India to escape the near daily violence in their homeland.

According to the United Nations Human Rights Council just 10,000 Afghan refugees are officially living in India. The country is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention on refugees, which asserts that “a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom.”

Oman Niazi, 50, a poet and an artist who makes paintings from sawdust and straw, lives a reality similar to Farhad’s. The author of six books of poetry in Pashto, Niyazi left Kabul along with his family some eight years ago after being threatened by a “Taliban affiliated group” for his work.

He fears his 13 year old daughter may never live a normal life, although he left his beloved homeland in hope that she would have a “regular” childhood. Despite his immense yearning for the homeland, Niazi doesn’t want to return.

“I don’t want her to lead the life I lived, or that any other child in Afghanistan lives,” he tells The Citizen.

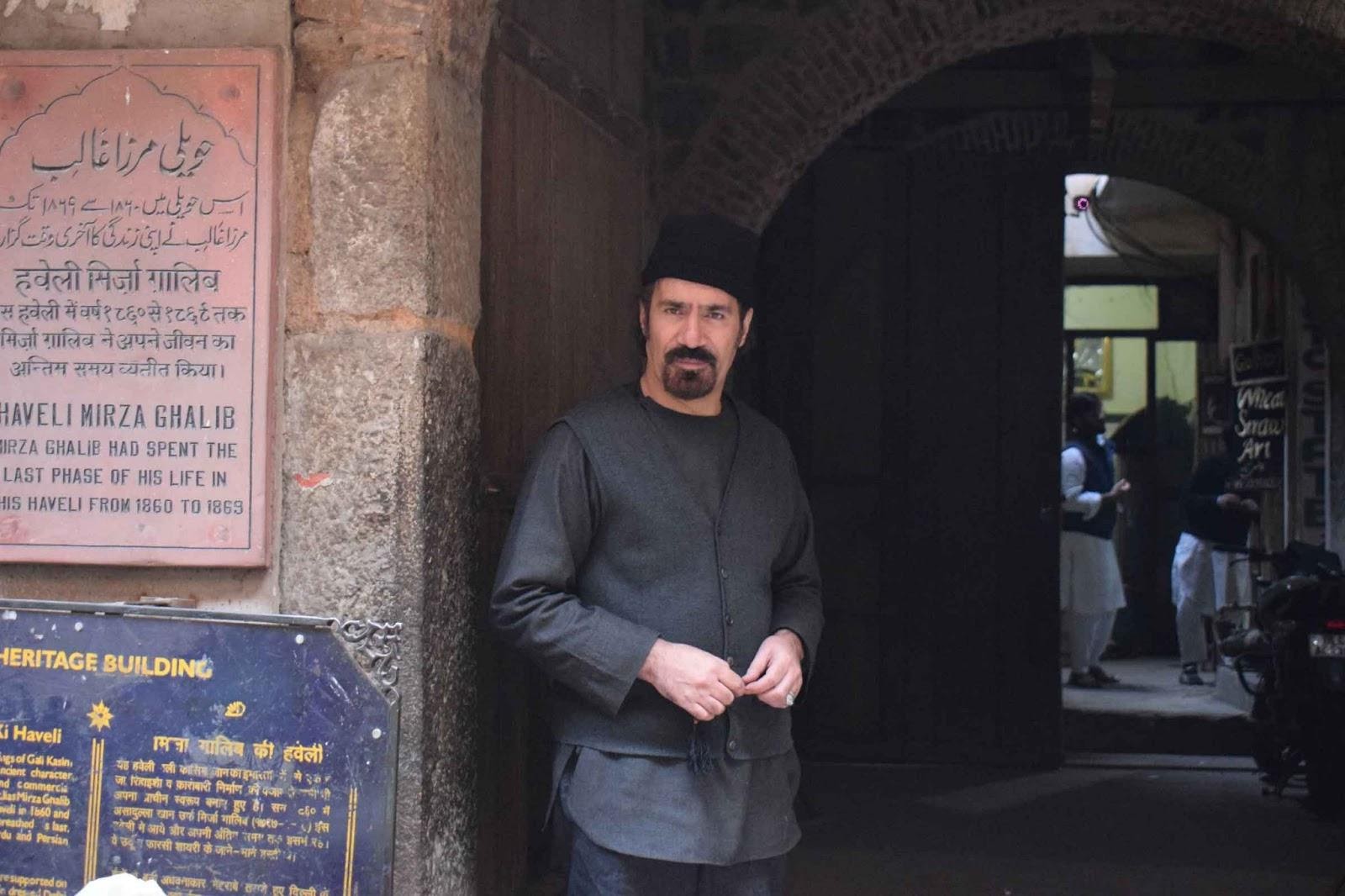

Niazi uses a technique of applying heat on wheat straws to carve out portraits. Although he has been lucky enough to rent space in a small gallery and shop in Old Delhi, the dwindling demand for Afghan paintings means he too must resort to making portraits of Indian celebrities.

“Though this is something new for me, it ensures better sales,” he explains.

“The condition of artists in Afghanistan is not good. The only way we can survive is by pursuing it in other lands. This will at least keep it alive.”

Like Farhad and Neyazi, many Afghans emigrated to India during the Soviet war in the late 70s and early 80s, and many more to escape the Taliban regime in the 1990s.

Rarely have they got Indian citizenship, which could help them lead normal lives. According to Union government figures it granted only 900 Afghan refugees citizenship between 2013 and 2019.

Usually, refugees get their annual visas extended based on the identity cards issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The controversial amendments to the Citizenship Act passed by Parliament last year will make it almost impossible for them to attain citizenship in the near future.

As per the new law, the process for getting Indian citizenship will be expedited only for non-Muslims from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Most refugees from Afghanistan, however, are Muslims.

Dawood Sharifi, head of the Association of Afghan refugees in India, who has been living in the country for the past seven years, says conditions for refugees are getting tougher by the day.

“We don’t get help from any relief agencies. My entire savings were spent during the lockdown. We appealed to them many times for help, but they don’t come forward,” said Sharifi, referring to the many UN agencies and affiliates.

“Many Afghan refugees were not paid wages by their employers during the pandemic. Some of them came to me for help. But unfortunately there is little that can be done.”

Photographs: Majid Alam