7 Months for SC to Deliver Verdict on Delhi-Centre Spat: Inordinate Delay?

7 Months for SC to Deliver Verdict on Delhi-Centre Spat: Inordinate Delay?

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court (SC) finally delivered its judgement on a batch of pleas on who enjoys supremacy over administration of NCT of Delhi. The apex court ruled that the Lieutenant Governor (L-G) cannot act independently and must take the aid and advise of the council of ministers in matters related to administration of Delhi. The five judge constitution bench has reversed the Delhi High Court’s judgement which had declared L-G as the sole administrator of Delhi.

Indeed, it is a welcome decision which reinforces elected government as the real administrator of Delhi but the fact that judgement was reserved for a period of almost seven months during which the administration of Delhi continued to be hamstrung by a lack of clarity over division of powers, cannot be ignored or justified. After hearing the arguments of both sides, the judgement was reserved by the five judge constitution bench led by CJI Dipak Misra on 6th December, 2017.

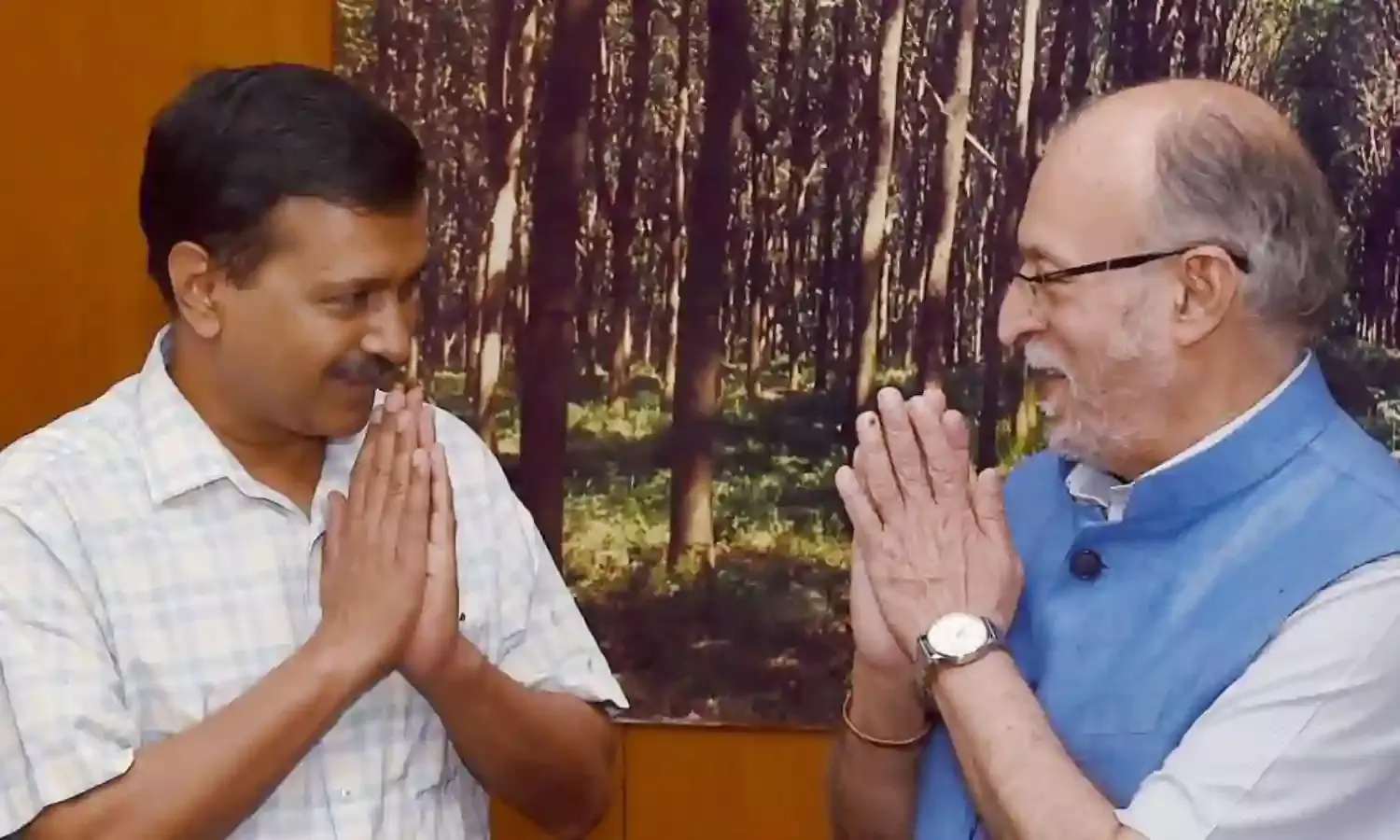

It took six months and twenty eight days for the Honourable Supreme Court to deliver the judgement. The continued uncertainty in the intervening seven month period over demarcation of power had far reaching implications on day to day functioning of an elected government. Undoubtedly the situation kept getting worse and Delhi’s administration was in a limbo when Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and his cabinet ministers staged a dharna over the issue of L-G causing obstruction in elected government’s functioning. According to a report of The Hindu, one of the advocates on behalf of the Delhi Government, Mr. Subramaniam had alleged that the L-G has misused the discretion in the proviso to Article 239AA(4) to block governance to such an extent that decisions from appointment of teachers in municipal schools to opening of mohalla clinics have been pending for over a year. The delay in delivering judgement in this case meant stalled welfare schemes as the L-G was sitting on files indeterminately.

Although, it is not correct to lay the entire blame for delay in proceedings on judges alone because the lawyers and parties to the dispute are also part of the proceedings but once the hearing of the matter is wrapped up and the judgment is reserved, it is the sole responsibility of the judges for inordinate delay (if any) in delivering the judgement.

What is the law on ‘reserving judgements’ ?

There is no provision of law which mandates a time limit to deliver the judgement after it has been reserved by the High Courts or the Supreme Court. Since there is no procedural law which sets the time limit to deliver the judgement, the Supreme Court held in the case of Anil Rai vs State of Bihar that the parties can file an application in the High court seeking an early judgement if it’s not delivered within three months of it being reserved. If it’s not delivered more than six months after being reserved, parties have a right to have it re-heard before a different bench of the high court.

In the present case like many other cases where the delay is long and unexplained, the Supreme Court has failed to adhere to its own informal timeline it had set for the High Courts, thus providing time and space for the differences between Delhi Government and L-G to fester which directly hampered the day to day governance of NCT of Delhi.

Why this case should have been given priority ?

When the Constitution of India was being drafted, it was hard to anticipate a dispute between Centre and Union Territories because a Union Territory (UT) was considered to be an instrument of the Centre under the direct control of President. For the Union Territory of Delhi, this status was altered by introducing 69th Constitutional Amendment Act which incorporated Article 239AA into the constitution. This amendment brought with it an unclear division of powers which is the root cause of the tussle between L-G and AAP Government. After the amendment, Delhi’s status was no longer similar to other UTs, it became a class apart. This altered status made this tussle one similar to a Centre- State dispute which required quick disposal on a priority basis.

The need for a Monitoring Mechanism

In the case of Anil Rai vs State of Bihar, the Supreme Court had prescribed a monitoring mechanism for High Courts to ensure that there is no inordinate delay in delivering the judgements. Ironically, the Supreme itself has failed in delivering the judgements on time. The information available on Supreme Court’s website is not sufficient to determine with accuracy how many judgements have been reserved and for how long. A monitoring mechanism will ensure transparency and accountability to litigants. It is perhaps the need of the hour for the apex court to adopt a monitoring system to keep track of reserved judgements so that cases can be prioritised and disposed off accordingly.

(Abhishek ‘Azad’ is a final year student at the Institute of Law, Nirma University, Ahmedabad)