'Even If I Die My Land Won't': Farmers March in Delhi

'We won't step back; if our demands are not fulfilled we will come back.'

NEW DELHI: The march from Majnu Ka Tila began at noon yesterday, with farmers shouting slogans like ‘Apne bachon ke liye halla bol’, ‘Narendra Modi murdabad’ and ‘Apne Haqq ke liye halla bol’.

The group comprised farmers from Punjab and Himachal Pradesh. Women and men marching together for their rights.

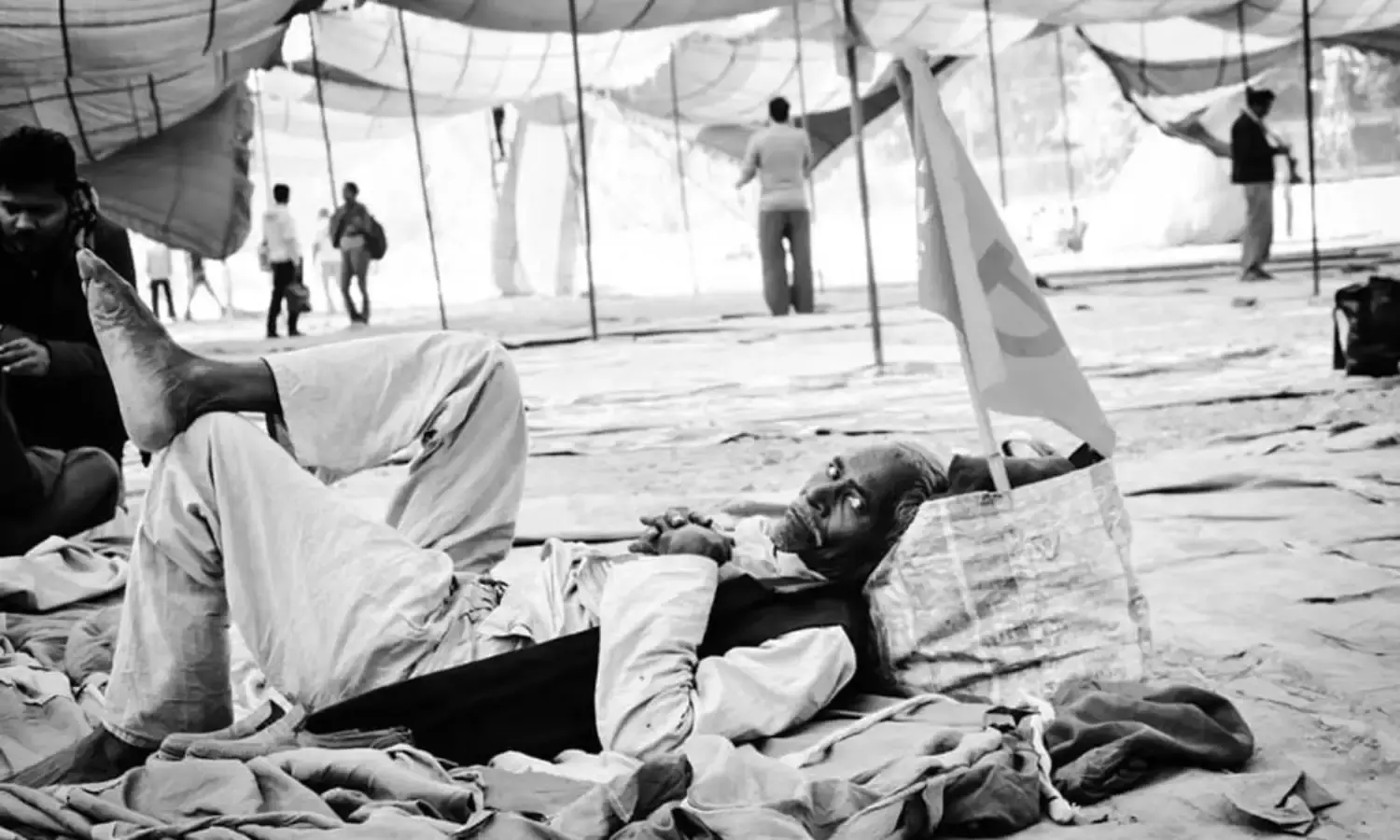

Most had reached Delhi on the night of November 28. They spent the cold winter night in tents or gurudwaras at the four different starting points – in south, west, north and east Delhi – for this march to Ramlila Maidan.

*

Many have come to the national capital leaving their children alone. They say we are doing this for their future. Struggle is the only way we know.

The crowd seems filled with many emotions: sorrow, hope, hopelessness, optimism, strong will, sadness. A kisan from Maharashtra told The Citizen, ‘The Congress government was stealing from our pockets, but this government is slitting our throat.' And said another, 'The country does not take notice of the people who feed them.’

A kisan from Himachal said, ‘We won’t step back; if our demands are not fulfilled we will come back.’

*

Nagesh, 24, is a kisan from Chihtamani taluk in Chikbalapur, Karnataka. He has come to Delhi with 10 other people from his district. His brother is 19 years old and works on the farm with Nagesh and his parents. He brother wanted to study, but could not afford to do so. Nagesh owns four acres of land, all of which is dryland.

He has applied for a loan many times, but says that farmers in the Chikbalapur district do not get loans. There is little enough hope for those with irrigated land, but dryland farmers are not lent even a penny. Nagesh has never thought of doing anything else for a living. Does he have hope of the march today? No, none, he responds.

*

Khandera Kanade, 58, is a kisan from Nander in Maharashtra. He owns 10 acres of land. Three generations of his family have farmed it. It’s his land, but on paper it belongs to the government of Maharashtra. There is no water supply there; they occasionally get electricity, but at times like midnight. To add to their problems, they can sell their produce only to private vendors, as the district has just one government authorised procurement shop. It buys only tur dal – and Kanade is still waiting for his payment for the tur he sold them a year ago.

The bank won’t lend to those older than 60 from fear that they won’t get it back, says Kanade. ‘But even if I die my land won’t, and money could be recovered from it.’ Soon he won’t be able to get loans. He doesn’t want his children to go into farming. He says he has no hope but doesn’t know any other way to make the government understand his problems.

*

Joshi Ashok, 56, from Ahmednagar in Maharashtra has a similar story to tell. He owns four acres of land. His son and daughter both study in school; he wanted them to get a good education but cannot afford it. He says there is no future in farming. ‘If I want a loan I will have to sign a legal agreement where I have to pay Rs 7000 for every lakh.’ He’s still waiting for the loan waiver promised him back in 2000.

‘In case of crop failure,’ he adds, ‘we only get Rs 1500-2000 for every 2½ acres of land.’ His children get no fellowship and it has become impossible for him to keep them in school with this meagre income. Forest department officers are other menace, as they charge them fines for farming their own land.

Farmers in Maharashtra get no pension, he says, and they are demanding a pension of at least Rs 5000-6000 for those above 60 years of age.

*

Sanjay Chauhan is a horticulturalist who owns a hectare of land in Himachal Pradesh, on which he grows apples. 90% of the state’s people live in rural areas. But only 16% of the land is cultivable, and the government has been trying to evict farmers from even this, on the pretext of preserving forests.

Chauhan completed his post-graduation 25 years ago and chose to become a horticulturalist, but today, he says he wouldn’t want his children to follow in his steps. ‘In fact if I could go back in time I would never choose to be a horticulturalist.’ With even a single crop failure in next 5 years his income will turn negative, and his savings will shrink.

‘Himachal Pradesh has a high literacy rate, but on finding no jobs in the state the youth have migrated to other states to earn their livelihood.’ In the last four years the productivity cost has gone up and Chauhan is unable to recover his production costs. He says farmers in the state are on the verge of extinction.

*

Seema Devi owns 5 bighas of land in Himachal’s Kullu district, on which she grows peas and cauliflower. But she is not able to cultivate even half the land because of the monkey menace. This has been a problem since time immemorial, she says, adding that she doesn’t even know for how many generations her family have been farming. But she doesn’t want her children to engage in it. All three of them study in school, she says, but ‘there are no proper schools or teachers for our children. We want them to study but we don’t have the resources. The children get no fellowship or fee waiver.’

Adding to their problems are the officers of forest department, who frequently raid their land and need bribing. Moreover, Seema Devi says, LPG rates have touched the sky. ‘I do not get subsidy, and the few of us who do get merely Rs 150-250. So we have to cook using firewood, and getting firewood for cooking is yet another big task for us.’

‘There are no hospitals for us, no gynecologist.’ Her husband accompanies her; she had to leave her children alone. On being asked how will they manage alone she replies she had no choice. ‘I came here with my own money, we are poor people and will die either that way or the other.

‘My children have no future, and whether or not the government agrees to our demand, struggle is our only way. We struggle at home, and we are struggling now on the roads of Delhi.’

*

Jugraj Singh owns two acres of land in Bhatinda, Punjab. He lives with his wife and two children. He cultivates wheat and rice, but there is no sale because the government says both crops are in surplus. ‘The government doesn’t buy our crop, nor does it allow us to grow any other crop on the land. We want to grow khus khus and opium, used in medicines. The government can have a ceiling on the amount of land that can be used for growing opium, but the government can buy all of it, we don’t want to keep it with us.’

He also mentions the problem of wild animals and the land mafia. And, that there has been no loan waiver by the new government. ‘25 percent of our youth are under the influence of drugs. There are two generations sitting at home with graduation degrees but there is no job to be had.’

The pension amount in Punjab is much lower than in Haryana. Says Singh, ‘I could not even get a loan of Rs 40,000-50,000. We have been farming for generations, but I don’t want my children to get into it.’ He wants them to study but he doesn’t have money to support their education. ‘Indebtedness is a major problem in Punjab.’