"Babri Masjid Is A Shameful Chapter in India's History": Godbole's Lecture Part 2

MUMBAI:Editor's note: This is the second extract from former Union Home Secretary Madhav Godbole’s intended lecture on Is India a Secular State, scheduled to be held at the Mantralaya in Mumbai on April 4, it was cancalled suddenly on April 1. Details of this along with the first extract from the lecture can be read here.

Demolition of the Babri Masjid is a shameful chapter in India's recent history raising serious doubts about its secularism. I was destined to live through this ignoble chapter at close quarters as the Union Home Secretary.

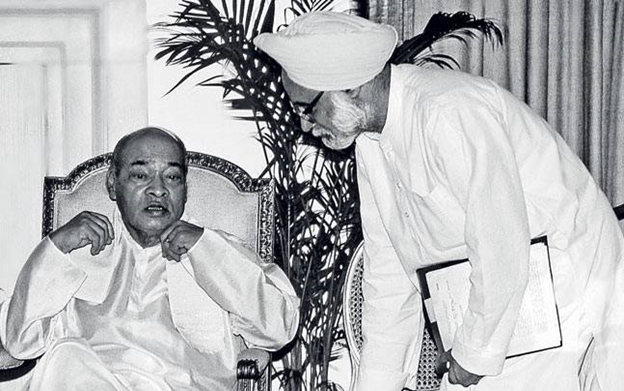

All efforts made by the Ministry of Home Affairs to avert the tragedy by resorting to action under article 355 (Duty of the Union to protect States against external aggression and internal disturbance) for taking possession and safeguarding the Babri Masjid by central forces, followed by imposition of President's Rule in Uttar Pradesh under article 356 (Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in States) of the Constitution were frustrated due to the disinclination of the Prime Minister to act.

P.V. Narasimha Rao in his book Ayodhya 6 December 1992 claimed that he was unable to take any action due to the restrictive provisions of the Constitution and that he was made a scapegoat by Congress party. This must be the only case of its kind in history in which the prime minister has alleged of being made a scapegoat!! Otherwise, it is the well accepted prerogative of prime ministers to find a scapegoat for each of their lapses!

The Ayodhya debacle has several other firsts to its credit. Prime Minister Rao's assurance of "rebuilding the mosque'' given immediately after its demolition on 6 December 1992 has remained on paper. Kalyan Singh, who was the chief minister of U.P. at the time and who had given assurances to the National Integration Council, the government of India and the Supreme Court to fully safeguard the Babri Masjid, has been elevated as a Governor by the NDA government. Earlier, the Supreme Court, before which he was hauled up for contempt of court, gave punishment of imprisonment till the rising of the court and a token fine of Rs 2,000! The judicial commission of inquiry under the chairmanship of Justice M. Liberhan, set up within a week of the demolition of the mosque, created a world record by taking 17 years to complete the inquiry and effectively found no one guilty! The CBI cases against the perpetrators of the crime are still languishing though 22 years have elapsed.

It is this callousness and connivance which goes to show how sham is India's commitment to secularism. On this background to call secularism a part of the basic structure of the Constitution makes no sense.

Equally disconcerting is the manner in which perpetrators of crimes in the widespread communal riots have been casually and leniently handled by the respective state governments.

In spite of appointing dozens of committees and commissions to identify those responsible in the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi, hardly any action has been taken against the leaders of the Congress party who are alleged to have instigated the riots. These riots took place under the benign leadership of the central government and were therefore all the more shocking.

The riots in Mumbai in December 1992 and January 1993 is another can of worms. Justice Srikrishna Commission has commented on them at great length. But the political parties and persons responsible have been permitted to go scot-free.

The usual adage of the law taking its own course has been held to ridicule. The Godhra riots were qualitatively different in that it was the state-sponsored violence against the minorities. The National Human Rights Commission and the Supreme Court have done a yeomen service in upholding the rule of law but the main issue of the urgency of reorganisation of police administration which has been highlighted by the judicial commissions as also the citizens' commissions again and again has been over-looked. Even the directions of the Supreme Court issued as far back as 2006 in a public interest litigation have remained on paper. What kind of a robust and vigilant democracy are we if even the orders of the highest court in the country are not to be implemented?

Finally, the question has to be asked whether banning cow slaughter is in keeping with the concept of secularism. The Supreme Court upholding the constitutional validity of these enactments by a majority decision of 6:1 on 26 October 2005 ((2005) 8 SCC 534) has closed all options, at least for the present. It proves the adage that the Supreme Court is supreme only because there is no appeal over its decision. As one of the judges of the Supreme Court had said, "If there were an appellate court over us, probably a majority of our judgments would be upset." It would also be worth recalling what Justice Brennan, a judge of the US Supreme Court, had said, "The Supreme Court [of United States] is not final because it is infallible; the court is infallible because it is final."

In a secular state, religion is expected to be a purely personal and private matter and is not supposed to have anything to do with the governance of the country. The Supreme Court had observed in the Bommai case that if religion is not separated from politics, religion of the ruling party tends to become the state religion. This seems to be coming true. The BJP and its affiliate parties have given to the prevention of cow slaughter sanctity of Hindu religious precept. But this is hardly justified. Further, the fundamental right of persons to practise any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business contained in article 19 (1) (g) of the Constitution has been over-ridden by article 48, one of the directive principles of state policy. In the scheme of the Constitution, directive principles are not supposed to override the fundamental rights. But, it has now become a sacrilege to even raise such questions. Economic justification for enforcing cow slaughter is also highly questionable. It is unfortunate that though Nehru was staunchly opposed to prevention of cow slaughter, he did not oppose the inclusion of this provision in the Constitution. In fact, the discussion in the Constituent Assembly shows that a political decision to incorporate this provision was taken in the Congress Party meeting and it was merely formalised in the Constituent Assembly by putting forth spacious and unconvincing arguments. This is yet another instance of the ambivalence of the Constitution on secularism.