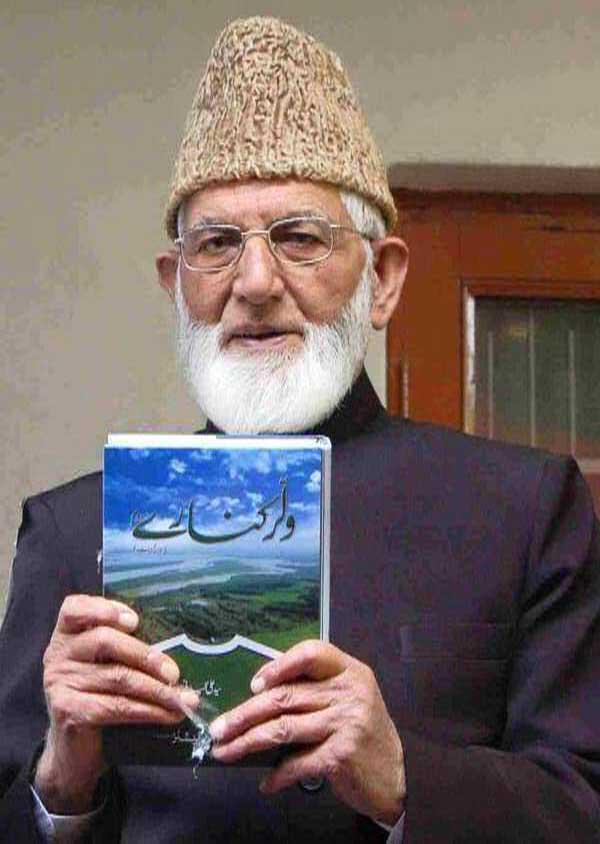

Geelani Attacks Musharraf in New Book

SRINAGAR: Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani, recently released his third volume of 661-paged autobiography entitled ‘Wullar Kinarey’ (‘On the Banks of Wullar’) in which he criticizes former Pakistan President, Pervez Musharraf, for offering ‘Four-Point Kashmir Formula’ to India, saying that the ex-military dictator was a victim of “acute mental depression” and had lost “self- confidence” because of which “he would come up with new proposals every second day.” (pages 407-08)

The 86-year old Kashmir’s pro-resistance leader Geelani accuses Musharraf of “going against Pakistan’s official position on Kashmir” to “satisfy his own desire”.

Musharraf, in December 2006, had offered a deal to India, saying that he was willing to give up Pakistan’s official claim on Kashmir if India agreed to a self-government plan and backed wide-ranging self-rule or autonomy for Kashmir, with both countries jointly supervising the disputed Himalayan region.

General (retired) Musharraf’s idea was that the borders and Line of Control (LoC) would remain as they are but could be made “irrelevant” through easy trade, travel and tourism.

In the third volume ‘Wullar Kinarey) Geelani focuses on different subjects and raises suspicion around the three-month conditional unilateral ceasefire offered by Kashmir’s largest indigenous militant outfit, Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, to India in 2000.

Abdul Majid Dar, Hizb’s then commander-in-chief (operations), announced that his outfit would “halt attacks” against Indian security forces in July 2000.

“The sudden ceasefire announcement made people of Kashmir suspicious about its motives. Why did the ceasefire happen? What were the factors involved? Whether or not the Hizb leadership across the border (based across the Line of Control, LoC, in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, PaK) was taken into confidence? What were the modalities and how would it have impacted the ongoing anti-India resistance? Like all other people, these important questions had made me restless and edgy, too” the author mentions in the chapter titled ‘Hizb-ul-Mujahideen Ki Jung Bandi’ (‘The Truce By Hizb-ul-Mujahideen’, page 227).

Geelani defends the armed resistance, arguing that even Indian freedom fighters like Subhash Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh had taken the same route to fight British imperialism and today they are glorified as “heroes” by their countrymen, but India vilifies Kashmir’s “freedom fighters” as “terrorists”.

The author lends his full support to the armed resistance and launches scathing criticism against those who suggest that the “role of gun is over” in Kashmir.

He articulates that “the political dispute (Kashmir) has turned into a full-fledged Indian military occupation because of which the entire nation is suffering since many decades. This issue is now a matter of life and death for us. It is the question of our honour and dignity…It has become the question of our faith and religion. It has become the question of protecting identity of the majority community (Muslims).”

He showers flowery praises on the ‘Jama’at-e-Islami’ as a socio-politico-religious organization in Jammu & Kashmir, but strongly questions the organization’s former chief (Ameer-e-Jama’at) Ghulam Mohammad Bhat for saying that “Kashmir is only a political issue”.

“Our boys did not pick up gun for recreation purpose. But they took up arms to put pressure on India to accept the reality that Jammu & Kashmir is a disputed territory and this dispute should be resolved, keeping in view its historical background,” Geelani writes under the theme ‘Jama’at-e-Islami Aur Bandooq’ (The Jama’at-e-Islami and Gun’, page 130).

Abul Ala Mawdudi, the well-known theologian and ideologue of ‘Political Islam’, founded the JeI in 1941 to promote moral values and Islamic practices.

The organization was founded in Jammu & Kashmir by late Saad-ud-Din (Tarabali) in 1964.

In “Wullar Kinarey-III” Syed Geelani talks candidly about his life, moments of joy and sadness, deteriorating health condition, anti-India summer protests of 2008-09-10, return of Kashmiri Pandits, Hizb ceasefire of 2000, the devastating September floods of 2014 and much more.

Inarguably, Geelani is the most popular pro-freedom Kashmiri leader right now and his followers admire him for his tough stand against India. Some, who adore him as an individual, do not necessarily subscribe to his political stand that “Kashmir is a natural part of Pakistan.” But his followers love to refer to him ‘Qaid-e-Inquilab’ (Leader of the Revolution).

His third and final volume of autobiography is divided into 94 different themes. As a reader one appreciates Geelani’s sharp memory to jot down important historical events about Kashmir, Pakistan and India but there are some minor lapses and factual inaccuracies in the book as well.

In the first volume of his autobiography Geelani had lauded the role played by Kashmiri Pandit teachers in the development of Kashmir’s society and talked in great length about Late Moulana Masoodi’s contribution in shaping his personality. He had described Moulana Masoodi as his teacher, guide and mentor.

Also, Geelani had held Sheikh Abdullah solely responsible for Kashmir’s “military occupation”, gross human rights excesses and “slavery”.

In the latest volume Geelani acknowledges that the minority Pandit community had to leave their homes in hostile circumstances of 1990s but suggests that the Indian government was very much part of the conspiracy in creating such circumstances.

“Pandits were terrified in a well-crafted manner and then they thought of migration, leaving their homes immediately, was the safest bet.”

(‘Pandit Baradari Ki Watan Wapsi’ ‘The Return of Pandit Community’ page 619).

He, however, does not specify who actually terrified the minority community but hints it was Indian state’s design. Because the author further writes that the Indian government offered various benefits and subsidies to migrant Pandit community in Jammu and other Indian states.

“The Indian government gave scholarships and grants in medicine, engineering, journalism and business; etc to the Pandit community, so much so that even the local population became envious,” he writes. (page 620)

Geelani says that the resistance leadership has always welcomed Pandit community’s return to homeland, but was averse to their return to “safe zones” constructed for the community members in Kulgam, Mattan, Shopian and Budgam.

“We will oppose tooth and nail the attempts to resettle Pandits in the safe zones, even if it means that the majority community has to offer financial and human sacrifices for that.”

The author also reasons that “Kashmiris started armed uprising in 1989 only after India had choked all democratic and peaceful space for a meaningful discourse.”

The veteran Kashmiri leader also admits that journalists in Kashmir have suffered from both the state and non-state actors during the past 25 years.

“From the government side there was always pressure on the media not to give coverage to the pro-resistance groups while the media industry also had to deal with demands made by the resistance groups that their press notes should get published in their newspapers without fail,” he writes.

The autobiography also talks about the killings of former Hurriyat chairman Khwaja Abdul Gani Lone, Hurriyat leader Sheikh Abdul Aziz, Advocate Hussam-ud-Din, death of Qazi Hussain Ahmad, chief JeI, Pakistan, Afzal Guru’s execution, Hurriyat’s split, the September floods of 2014, etc.

Author: SYED ALI SHAH GEELANI

Publisher: Millat Publications, Srinagar

Pages: 661