AMU Part 2: Why Were So Many Intellectuals in Aligarh Drawn to Marxism?

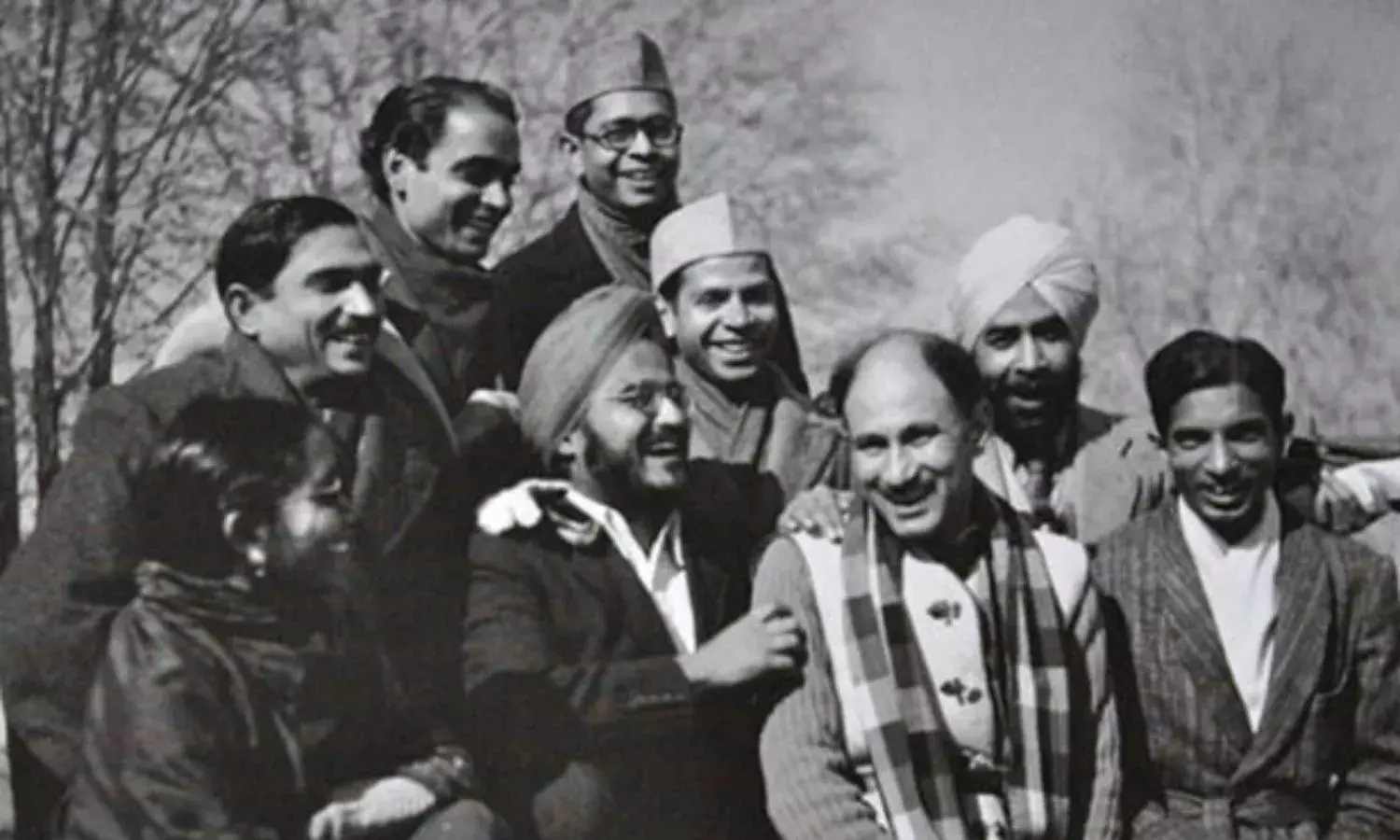

Khwaja Ahmed Abbas with writers Navtej Singh and Rajinder Singh Bedi (cover photograph)

Editors Note: Professor Mushirul Hasan, a world renowned historian, and alumni of Aligarh Muslim University wrote this excellent article in 2003 for the India International Centre quarterly. An important voice Hasan is not well now but this article remains relevant today when the Aligarh Muslim University is under attack from right wing forces who have little idea of its history, and absolutely none of the contribution it has made to the pluralistic, secular discourse of India since. The Citizen with permission from Zoya Hasan, a scholar and wife of Professor Hasan, is reproducing the article that places AMU in the midst of Indian history.

For one, the processes had begun in the 1920s when attempts were made to synthesise socialism with Islam. This was the legacy of the firebrand Urdu poet, Hasrat Mohani. In the 1930s, socialism was the new revelation that young idealists could invoke to exorcise communal rancours, by uniting the majority from all communities in a struggle against their common poverty, and to make independence a blessing to the poor as well as to the elite.

Their fervour played a considerable role in the widening gap between the 'left' and the 'right', as people began to say. The university had on its rolls Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Sardar Jafri, Sibte Hasan, the writer who migrated to Pakistan, and Ansar Harvard, founder of the Students Federation and a devoted follower of Subhas Chandra Bose.Abbas and Ansar Harvani wrote their memoirs that, sadly, so few have read. These capture life at Aligarh vividly.

Eventually though, the radical trends, though kept alive in certain circles, were overwhelmed by the tide of Muslim nationalism. However, once the Aligarh architects of Muslim nationalism left for Pakistan, the socialists and the communists, encouraged by Zakir Husain, moved to Aligarh from many places in north India. Socialism carried the same poetic and romantic appeal as poetic blasphemy in the works of the Persian poets Hafiz, Mirza Ghalib, and Hasrat Mohani. When Hindustan published Asrarul Haq Majaz's poem Andheri Raat ka Musafir (The Traveller in the Dark Night'), the poem inspired his young readers. One line ran thus:

Khuda soya huai hai, Ahraman mehshar ba-daman hai

God is asleep and Ahirman comes bringing doomsday to him.

This is not to suggest that Aligarh had suddenly become the stormcentre of the Communist movement. It had not. The Students' Federation was still a tame affair, drawing only a handful at Al-Hamra, the study circle tucked away across the imposing Sulaiman Hall Gate. Internal factions reigned supreme, and endless ideological wrangling was the order of the day. As a result, the left front split into numerous fractions.

The traditional elements in Aligarh society, spearheaded in the 1950s and 60s by the pro-vice chancellor, Dr. Yusuf Husain Khan, were strong—so much so that girls were prohibited from appearing on stage. The History Department had its own share of traditionalists, who were invariably pitted against the left historians. Hence, both Satish Chandra and Mohibbul Hasan had to leave Aligarh.

Amidst the cacophony of noises, it is quite remarkable that a number of women teachers and students occupied the cultural spaces. Though the butt of ridicule and criticism, the three Zaidi sisters, as they were known, actively organised mushairas and music concerts and staged plays.

Unconventional in their demeanour and often provocative in their style, especially when one of them would light a cigarette in full public view, they were serious academics and at the same time, activists. Grand daughters of the leading poet and writer, Altaf Husain Ali a contemporary of Syed Ahmad Khan, Sabira, Sajida and Zahida broke away from family traditions to bring much richness to Aligarh's intellectual and cultural ambience.

Ghazala Ansari was one of their colleagues, and her brother Ziaul Hasan was a communist working with the Patriot for years. So was her husband Anwar Ansari, a soft-spoken individual who belonged to Lucknow's traditional Firangi Mahal family. Although the Tyabji family in Bombay had established this trend of women breaking away from established family traditions in Bombay, it was not so common among Muslim elites in north India.

By the time I entered the university in 1964 the Progressive Writers' Movement had withered away. Yet, Aligarh had its share of Progressive Writers and poets. Prominent amongst them was Khurshidul Islam, overshadowed for a while by Rashid Ahmad Siddiqi, head of the department. Ale Ahmad Suroor had also moved from Lucknow to Aligarh in the mid-1950s, often mistaken for my father owing to a striking resemblance.

Moin Ahsan Jazbi was around, but his poetry had lost its old vigour; so was the young lecturer Khalilur Rahman Azmi, who had been stabbed, thrown out of the train, and left for dead during the Partition violence. We had easy access to Waheed Akhtar, a fine writer and poet who taught philosophy, and the brilliant up-coming poet Shaharyar whom I got to know well as a post-graduate student.

Asghar Bilgrami, the political scientist, was one of our favourite teachers. Invariably, he talked of his days in Geneva and complained of Aligarh's stifling atmosphere. He, Jamal Khwaja, the philosophy professor, and Aulad Ahmad Siddiqi, the economist, extended their fulsome support to our liberal concerns. They patronised the Secular Society that was needlessly targeted by the CPI (M) group.

In 1968—69 the hub of cultural activities was Kennedy House, with its imposing mural by M.F. Husain. While the muezzin called the faithful to prayers, one could hear Beethoven and Mozart in one of its music rooms specially devoted to western classical music.

Or, one had the option of listening to Indian classical music. For the all-night qazvivali sessions, we'd go to the shrine of Barchi Bahadur, a little distance from the district court; for nautanki, Farid Faridi's favourite pastime, to the exhibition ground. Thanks to Asadur Rahman, the English lecturer and his vibrant wife Shaista Rahman, one had a fair mix of English plays.

My brother took the part of Teiresias in Oedipus Rex of Sophocles, the lead role in Galsworthy's She Stoops to Conquer and acted Gentleman Caller in Tennese William's Glass Menagerie. He also acted in George Bernard Shaw's Arms and the Man. Rahman's departure to United States and joining Brooklyn College created a void in our lives.

Lest I forget, the star performer then and later was, admittedly, Naseeruddin Shah. He and I took part in a Mock Parliament session in Delhi, and in a debating competition held at Jaipur. Muzaffar Ali, then a painter, Asghar Wajahat, now a famous creative writer in Hindi, Madhosh Bilgrami, and Humayun Zafar Zaidi were a part of a lively literary group. They congregated at a friends house on Marris Road and exchanged their poems over rum and whisky.

Aligarh was the site of not just the annual mushaira held at the sprawling Exhibition Grounds across the railway line—the great divide between the town and gown—but equally within university precincts. Thus we had the good fortune of listening to Firaq Gorakhpuri, Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Akhtar-ul-Iman, Sardar Jafri, and KaifiAzmi.

I recall Makhdoom reciting Ek Chambeli ke Manwa tale at Al-Hamra, Firaq prefacing his ghazal with 'Bhaiyya-re' and Akhtar-ul Iman, the poet from Anglo-Arabic College (now Dr. Zakir Husain College) and Aligarh-educated, reciting the following lines from his poem 'The Footprint' or Nacjsh-i Pa:

Where have life's travellers gone?

Nobody knows.

What is this world?

No beginning, no end.

The shackles of time yet bind it so fast.

Where can I stand free of those chains?

Yet, Aligarh had its pitfalls. Facilities at the university were excellent, but, with few notable exceptions, the institution did not produce scholars or scientists of excellence. Most people were obsessed with the preservation of the university's 'minority' character, and their conversations centred round the future of the minorities. There were no bookshops, except the Naya Kitab Ghar, run by Kishen Singh, an enthusiast communist, and married to the sister of the surgeon Nasim Ansari, also a member of the Firangi Mahal family. Social life, too, was restricted. There were no restaurants and no decent cinema halls, except for Tasvir Mahal that screened English films only on Sundays.

With limited avenues for self-expression, faculty members developed lazy habits. Comfort and leisure was all that mattered to them. Although Delhi was only eighty miles away, a distance covered by the Kalka Mail in just three hours, the capital seemed beyond the realm of most people's imagination.

The segregation of boys and girls was still maintained in lecture rooms—though the winds of change were beginning to alter attitudes. More and more young women from the Women's College would hop on a rickshaw and travel to the campus to take part in cultural and literary activities.

It was difficult for them to visit hostels, but Barbara, later married to my brother Najmul and my friend Salma turned out to be more defiant. More often than not, opportunities of meeting one's girl friend were limited to Friday afternoons. That is when we would dress up and head towards the Women's College, a remarkable institution headed by an equally remarkable lady, Mumtaz Haider, the mother of Salman Haider, India's former Foreign Secretary. She was indulgent towards our group, and supported our activities, including the publication of a fortnightly magazine, Domain, edited by my brother (the first issue in 15 October 1967). Jokingly, she'd refer to us the English-speaking types as the 'East India Company'.

Though the forces of traditionalism were entrenched, they were hardly visible to us, the students. I had a taste of their strength much later in 1968, when the traditionalists, accusing me of being a communist and a pseudo-secularist, which I was not, mobilised their resources to defeat me in the Student's Union election.

Of all persons, Muzaffar Alam, a Deoband alim and now Professor at the University of Chicago, issued a fatwa in my support. Whether this or the hard work put in by my liberal/secular friends tilted the balance in my favour or not is hard to tell. What brought comfort to all of us was the narrow margin of my defeat. Liberal and left wing teachers, who had predicted my defeat by a huge margin, expressed much joy at my performance. The Vice-Chancellor Ali Yavar Jung was particularly delighted, and soon, I became his unofficial ambassador to various educational institutions.

Ali Yavar Jung became, tragically, the victim of a massive conspiracy. A group of students, backed by teachers and by certain key administrators, organised a brutal assault on his life on 25 April 1965. Today, that incident reminds me of my own trials and tribulations at the Jamia Millia Islamia from April 1992 to September 1997. Ali Yavar Jung, a suave person with an extremely dignified appearance, was targeted, along with some left-wing teachers that were present at the meeting of the University Court. Ali Yavar Jung's courage and resource did not fail during this desperate time. Yet, this was Aligarh at its worst. Battered and bruised, I remember some of them turning up at my sister's wedding on the same evening.

This assault traumatised campus life for years to come. M.C. Chagla, the Education Minister, over-reacted; and the ensuing ordinances stifled Aligarh's otherwise liberal and democratic ethos. Thereafter, a retrograde legislation which the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi disapproved, was pushed through. Though left-wing intellectuals berated the ordinance, their support in the university had steadily eroded owing to personal squabbles and sectarian visions.

Tired and aging leftist stalwarts faded into oblivion. Others moved elsewhere; Moonis Raza to Srinagar and Nurul Hasan to Delhi, first as member of Rajya Sabha and later as Minister of Education. Historians like Irfan Habib kept the CPI (M) flag flying doggedly; but most saw the prospect of a revolution fading before their eyes. This symbolised the death of a radical tradition.

Zakir Husain had claimed in 1955: 'The way Aligarh works, the way Aligarh thinks, the contribution Aligarh makes to Indian life ... will largely determine the place Mussalmans will occupy in the pattern of Indian life.' Aligarh has negotiated with its past and succeeded in creating a niche for itself in the country's academic structures. At the same time, its alumni face the uphill task of preparing the fraternity of teachers and students to meet the challenges of this millennium. They need to complete Syed Ahmad's unfinished agenda of fostering liberal and modernist ideas and take the lead, once and for all, in debating issues of education, social reforms and gender justice. They need to interpret Islam afresh in the light of world-wide intellectual currents, come to terms with the winds of change and guide the 120 million Muslims within the framework provided by India's democratic and secular constitution, and equip them to cope with the harsh realities of life. This is what the great visionary Syed Ahmad would have expected them to do. Marshall Hodgson observed over two decades ago, 'the problem of the Muslims of India is the problem of the Muslims in the world.'

Observed one of the university's alumni in 1976:

Aligarh needs to be shaken out of the ennui that has set in. With India's largest population of educated, intelligent Muslims collected in one place, Aligarh can provide, by its example and its ideas, the lead to the rest of the community. Muslims will have to pull themselves together, end the search for scapegoats and do something to help themselves. Minorities can never survive on government doles.

Read Part 1: http://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/4/14053/AMU-Inheritor-Not-of-Colonial-Rule-and-Partition-But-of-a-Modernist-and-Reformist-Legacy