Thomas Reuters Foundation Survey: Measuring Safety, Generating Outrage

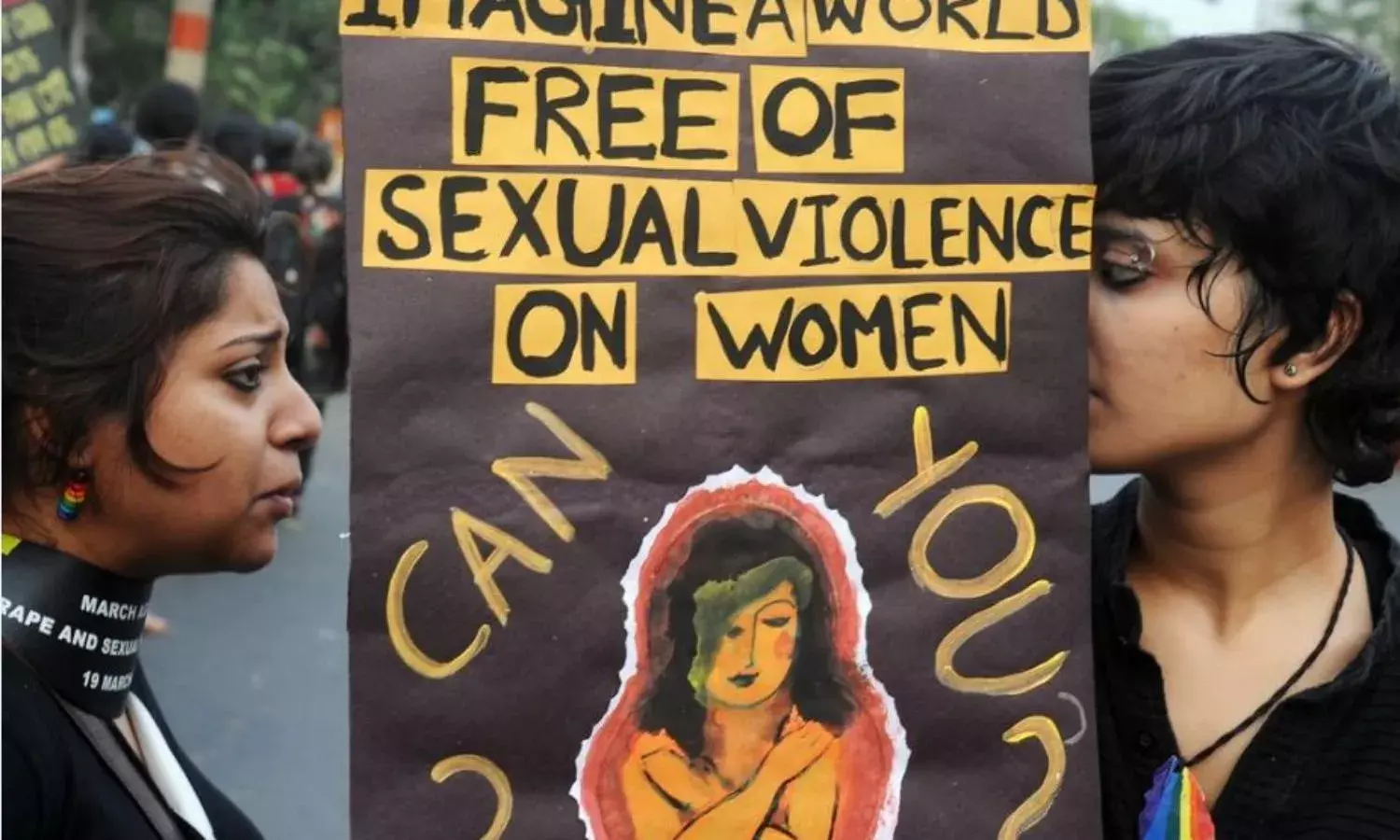

Any kind of story-telling around gender violence can only help

When the 2011 Thomson Reuters Foundation survey results were announced, I had misgivings that remain seven years later. But let’s start with what is good about this survey.

As someone who works year-round to start conversations about gender-based violence, how to recognise, respond to and report it, I am delighted when anything is able to get people talking.

Anything that has us asking—Is it really this bad? Why do they say this? —and reading the results (which too few do) is a good thing. From the point of view of advocacy, dramatic findings like ‘most dangerous place for women’ are gold, because they draw the kind of attention to an issue that tempered statements with statutory cautions do not.

I appreciate too how they have tried to arrive at a measure of safety. They have asked questions about health, about discrimination, about cultural and religious practices, about sexual and gender-based violence (including conflict-related violence) and about trafficking. There are still not many large-scale attempts to do this. Every attempt to define an abstract and necessarily relative idea (like safety or welfare) deepens our practical understanding of how it can be improved.

The 2018 survey is billed as a ‘perception poll.’ That is, 548 experts were asked to answer six questions and their answers were analysed to come up with these overall scores.

In a world of almost 8 billion, one does not have to be trained in statistics to see that this is not more thorough than a friends-and-cabbies analysis of a place one visits for a few weeks. One returns with good hunches that may well be correct, but hunches are not what we now consider sound knowledge. This was my issue in 2011 and it remains so now.

With India moving up from fourth place to first, winning the title of ‘most dangerous country for women’ ahead of Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Saudi Arabia and horror of horrors, Pakistan, the report has attracted a great deal of opprobrium.

It would after all, given the way we now think, be dishonourable and anti-national to accept such an honour—far more so than to countenance the escalating levels of everyday violence in our society. “How dare you say this about India?” seems to be the most common reaction of those who must instantly react.

Politicians are quick to seize opportunities that come their way. In 2011, Narendra Modi pointed to the same survey and lamented the fate of Indian women. In 2018, Congress politicians have pointed to it and held the present government responsible.

Neither has the courage to face up to the reality—Indian patriarchy is a hardy beast, protected fiercely by government and nurtured lovingly by family. A sense of entitlement is buttressed by the culture of impunity. It would be too much to expect political parties in India, led and funded mainly by men, to adopt good gender equality practices. The blame game is easier.

In the circumstances, for many Indian feminists, the report poses a challenge. To challenge its findings on the grounds that its methodology leaves something to be desired is to place oneself on the same side as those who might point to the number of good Indian men who take care of their wives and daughters—a point of view that is naïve at best.

After all, we have been trying to say to anyone who would listen that the life of an Indian girl or woman is a Hobbesian reality—“nasty, poor, brutish and short.” How could we repudiate a report which says the same thing, and how petty must our qualms about methodology sound?

As I reflect, I think my misgivings arise from the ranking. “Most dangerous” or “least dangerous” are in fact, meaningless terms for the Indian girl whose path to school is an obstacle course or the Swedish woman who has been raped by her date. Each woman’s security assessment is unique and absolute.

One may be safer in a mob than in her own bedroom; another may be protected and privileged but still insecure in her workplace. What difference does the label make to any of their lives or their prospects of greater safety or security? If anything, defensive governments and outraged patriarchal social elders are likely to dig in their heels, refuse to engage and reinforce the kinds of protection that in fact place women and girls at risk—dress codes, curfews, moral policing and paternalistic speech.

It is also hard to ignore the whiff of something neocolonial in a report by a UK-US based charity that lists ten countries, nine of which are non-western and the tenth, Trump’s America. Responding to the label ‘most dangerous’ leaves us with few middle options. Did we need a foreign study to tell us how bad things are? Are they telling us this because we may not be smart enough to notice or political enough to change it? What will we gain or lose with this label with reference to our own older-than-a-century efforts to transform our society? Is there any productive use to which I can put this ranking? It is not clear to me.

Moreover, the Poll website lists only the ten most dangerous; we do not know how the other 183 countries fare. This is one of the differences between the Reuters Foundation poll and the Women, Peace and Security Index which was the subject of an earlier article.

The Poll site tells us who fares worst but there does not appear to be enough information from the poll in the public sphere to put this in any context, local or comparative. The Index lists all countries studied and so you can understand where and why one fares better and one worse.

The Poll rightly points to the lack of reliable and consistent data on safety and substitutes for this, expert interviews. This weakens the enterprise. The Index operationalises well-being and empowerment along three dimensions, inclusion, justice and security, each of which are made up of three measures. These measures are drawn from public domain databases, national and international. This data may be flawed but we could make the case that they are less subjective than a relatively small number of interviews.

If I were asked to differentiate substantively between the Reuters Poll and the WPS Index, I would also say that the Poll looks at ‘safety’ while the Index looks at ‘security.’ There is a difference.

Safety is one dimension of security, which is also determined by food security, health, well-being, livelihoods, rights and participation. Safety is the most immediate and tangible dimension of security, but without the rest, remains always imperilled. When our discourse focuses on safety, it is still possible to ask paternalistic and patriarchal questions about keeping ‘our women’ safe and putting them behind protective walls. Shifting the focus to security opens up questions about justice, equality and freedom, and the walls must be dismantled in order to address them fully.

Asking about a narrow subject—safety—within a small community of anonymous experts, the Reuters Poll may be well-intentioned but it could lead our discussions in unproductive directions. Yes, the dramatic label ‘most dangerous’ draws our attention but it does not seem to do so in a productive manner. And when we use it, perhaps like a bright highlighter to emphasise the import of our work, we do not necessarily expand the potential of our work to make real change. We simply impress in the moment, and only those who may neither know the issue nor the places involved.

Should the Reuters Foundation cease and desist in its polling efforts because they are flawed? Of course not. Any kind of story-telling around gender-based violence can only help us raise levels of awareness and social responsibility.

The Foundation is correct in saying in defence of its methodology there is not enough consistent data that can be used reliably. Reliable empirical research is expensive and complicated; but doing nothing may be worse. For those who like numerical measures, this poll is a useful dipstick and it serves the purpose of getting us to talk about violence, how common it is, how we are doing so little about it and also, how little good data we have.

Perhaps, we are the ones who need to change our perspective and not see the Poll as a final, authoritative verdict, to be swallowed or challenged, but simply as one way to capture a story that is worth telling a hundred times till it changes. Getting angry about the Poll misses the point it tries to make. That energy is better used changing the world.