The Perception of Being Discriminated Against is Overpowering

Reforming criminal justice to stop targeting ‘minorities’ in India

Minority rights in India’s criminal justice system are in dire straits as revealed graphically in the institutional murder of Father Stan Swamy, the Adivasi rights activist. The authorities’ indifference to end such horrific human rights violations is also brought out in several recent reports.

Persisting violence and crimes against minority Muslims, Christians, Sikhs and ‘national or ethnic minorities’ (UN terminology) elsewhere in India including the northeast, where I was posted for several years, pose a challenge to India’s criminal justice system. The matter came up for serious consideration at the 8th session of the UN Forum on Minority Rights in the Criminal Justice System in Geneva in November 2015. The report of UN special rapporteur Rita Izsak on the subject was presented to the 70th Session of the General Assembly.

As an expert invitee I made presentations at the four sessions of the UN meeting mentioned above.

- The criminal justice system in India vis-a-vis minority rights, especially of Muslims, Christians and ethnic communities in the northeast, is in virtual collapse. Members of these communities are being implicated in false cases, ill-treated and tortured.

- The Supreme Court of India has said that the majority of the arrests made by the police are illegal or unnecessary.

- Some time ago, a south Indian volunteer agency found on the basis of field investigations mainly in the north that about 1.8 million people, many of them from minority communities, were being tortured in police custody every year. This is likely an underestimate.

- Extrajudicial executions or ‘encounter killings’ of the minorities are replacing torture as the main method of police investigation. Such murders have occurred in several parts of the country including Jammu and Kashmir, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, the Central Tribal Districts, Manipur, Nagaland and other northeastern states.

- An ‘encounter’ is an event in which the police shoot dead a person and later claim falsely that the person was killed when he undertook an alleged ‘encounter’ with the police.

- The entire criminal justice system created by the colonial authorities was retained uncritically by the Indian elite.

- Penal and procedural codes enacted by the British in India in the 1860s mandate the suppression of people’s protest. Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1861 prevents the gathering of more than five persons as an ‘unlawful assembly’. More recently, sedition is the more favoured section of the law imposed in India.

- The Indian Penal Code begins with chapters on ‘criminal conspiracy’ and ‘offences against the State. The prevention and detection of offences, the main task of the police, is relegated to Chapter XVI and Section 299. The offence of ‘sedition’ was included in the Code in 1870. The Criminal Procedure Code 1861 and the Police Act 1860 make it possible for the police to violate human rights on a large scale.

- The Supreme Court has said that ‘dehumanising torture, assault and death in custody are so widespread as to raise serious questions about the credibility of rule of law and criminal justice’.

- The Second Administrative Reforms Commission, 2007 noted the ills of the Indian police: ‘politically oriented partisan performance, corruption and inefficiency. The public complained of rudeness, intimidation, suppression or concoction of evidence and malicious padding of cases’. 80% of the people surveyed said they had to pay a bribe in their dealings with the police. Of the 11 public agencies surveyed, police were found to be the most unsatisfactory.

- ‘In the name of investigating crimes, torture is inflicted not only on the accused, but also upon bona fide petitioners, complainants, informers and innocent bystanders’. These provisions disproportionately affect minorities.

- Police training is abysmal.

- In 2003 the Justice Malimath Committee was set up to reform the criminal justice system but its recommendations have remained on paper.

- The Indian judiciary is overburdened with a huge backlog of cases.

The Constitution of India does not define minorities. It only refers to them and speaks of minorities based on ‘religion and language’. Their rights are spelt out in Part III on the Fundamental Rights, which are legally enforceable.

The Government of India set up a National Commission on Minorities in 2005 which mentions five religious Minorities: Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Zoroastrians. The Jains were added in 2014.

The Ministry of Minority Affairs and the Ministry of Home Affairs in the government of India deal with minority issues.

The UN Declaration of 1992 mentions ‘National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities’. This is a comprehensive phrase which goes beyond the category of the six religious minorities mentioned by the National Commission on Minorities.

It is necessary for India to adopt a comprehensive term and include national, ethnic and linguistic minorities. The Constitution of India needs amending to take into account the violence, especially against the Muslim minority, that has been going on for a long time and has recently intensified.

There is also increasing violence against other minorities such as the indigenous communities in central and northeastern India, which are not included in the approved list of the National Commission for Minorities.

The Commission has the powers of a civil court and can summon witnesses. The Constitution needs to be amended to give it criminal powers of the level of a High Court. The same should apply to the National Commission for Women and the National Commissions for the SCs and the STs, along with the existing National Human Rights Commission.

In view of the existence of a multiplicity of minorities in India and in view of the conflicts emerging from identity assertions across the country, the Constitution must be amended to revise the definition of the term ‘minority’ and enumerate the categories including religious, linguistic, national, ethnic minorities.

It must also incorporate specific provisions for the protection of minorities from all forms of violence, and provide them justice and fair play in the criminal justice system.

The Preamble to the Constitution of India declares India to be a ‘secular’ state (this is of special relevance to religious minorities) and to secure to all ‘liberty of thought, expression, faith and worship and equality of status and opportunity.

Significant also for the minorities is the elimination of inequalities ensuring their welfare as for the weaker sections, besides the Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

The Muslim, Christian and Sikh minorities have been subjected to extrajudicial executions, torture, rape, intimidation, and implication in false cases, destruction of property and utilities and other illegal acts under the criminal justice system. Non-listed minorities in the northeastern region too have been subjected to similar abuses.

The Sikhs were subjected to genocidal killings after some members of the Sikh security forces assassinated Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in protest against the killing of Sikhs during and after Operation ‘Blue Star’ in 1984.

The genocidal killings of the Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 and the attacks on Christians in Orissa in 2008 also violated the norms of the criminal justice system.

There are no specific protective legal provisions for the minorities in the Indian Constitution. The police, prosecution and judiciary are not sensitised to minority issues and function within the existing framework of law and order.

International principles and standards on minority issues are yet to be incorporated in the Indian criminal justice system.

The Justice Rajinder Sachar Committee Report 2005 was the first of its kind in India to provide insights into the socioeconomic and security issues facing the Muslim minority which constitutes 13.4% of the population.

The report states that:

i) Muslims in India face a double burden, in that they are regarded as anti-national and are at the same time said to be pampered by the government

ii) The police are high-handed in dealing with Muslims; whenever an incident occurs Muslim boys are ‘picked up’ by the police

iii) The state does not function in an impartial manner, the acid test for a just state

iv) Muslims, the largest religious minority in India, are lagging behind other Indian communities in terms of most human development indicators

iv) ‘Every bearded man is considered an agent of the Pakistani Inter Service Intelligence’

v) Fake encounter killings of Muslims are common

vi) Police presence in Muslim areas is more common than the presence of industry, schools, public hospitals, banks and the like

vii) Security personnel enter Muslim homes at the slightest provocation

viii) The plight of Muslims living in border areas is worse, since they are treated as foreigners and are subjected to harassment by the police and the administration

ix) Violent communal conflicts often include targeted sexual violence against women, which tends to have an effect even in areas not targeted by communal violence

x) The immense fear and feeling of vulnerability that prevail have a visible impact on mobility and education, especially of girls

xi) Underrepresentation in the police force accentuates the problem in almost all Indian states, and heightens the perceived sense of insecurity, especially in a communally sensitive situation

xii) Insecurity leads to Muslims living in ghettos

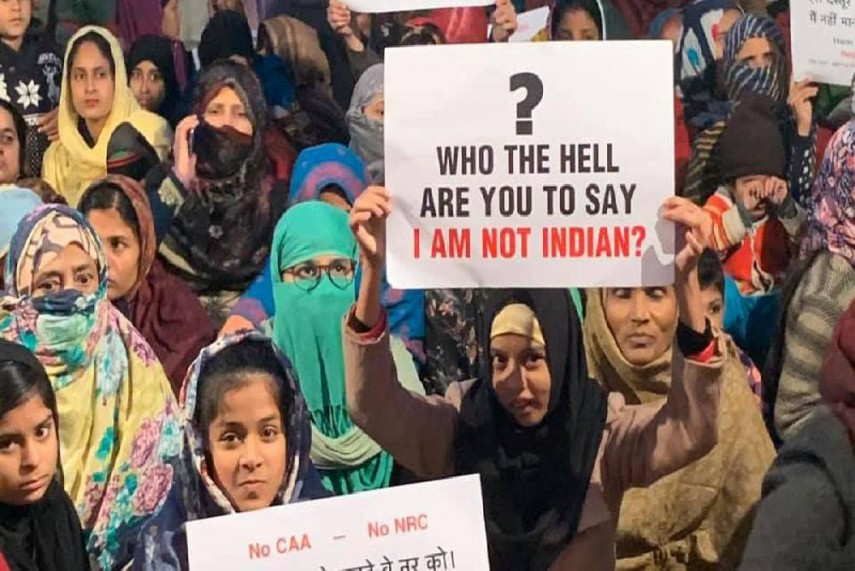

xiii) The perception of being discriminated against is overpowering amongst a wide cross-section of Muslims, resulting in collective alienation.

The new anti-terrorist politics have encouraged the devaluation of the criminal justice system and its perversion, resulting in the prosecution of innocent Muslims not involved in terrorist activities yet falsely implicated by the police in such cases in order to obtain government recognition and rewards. Far from getting any specialised attention and protection, the minority communities, especially the Muslims in India are targets of police harassment on allegation of ‘terrorist’ activities.

This problem is clearly brought out in a study which documents the registration of false cases against innocent Muslims and ethnic minorities from the northeast being subjected to systematic police harassment, cruelty and torture and false criminal cases under special security legislations involving prolonged imprisonment and more. (‘Framed, Damned, Acquitted: Dossiers of a Very Special Cell', A Report by the Jamia Teachers Solidarity Association, New Delhi.)

The Criminal Procedure Code, 1861 has chapters on security for keeping the peace and maintenance of public order including use of force by the police, which take precedence over the investigation and trial of criminal offences.

The Police Act of 1861 prioritises the collection of political intelligence. Prevention and investigation of crime is only from section 23. It provides for punitive policing: police officers are vested with vast powers and even the constabulary vested with vast powers. The persistence of repressive colonial laws has contributed to the unpopularity of the police.

In 1856 the British government said, “The Indian police are all but useless for the prevention and sadly inefficient in the detection of crime; unscrupulous in the use of authority they had a generalised reputation for corruption and oppression”.

David Bayley, a leading authority has said, “Police officers are preoccupied with politics, penetrated by politics and participate in it individually and collectively.”

Anti-minority carnage in Gujarat, 2002

There were multiple failures in the functioning of the police. They did not focus on the Hindu fundamentalists who were the real culprits. They delayed imposition of the curfew; neglected criminal law and acted under political influence; their intelligence was poor; they facilitated and participated in the violence; neglected rape victims; allowed criminal Hindu mobs to have their way; they ignored recommendations of the National Human Rights Commission; failed to impose the Disturbed Areas Act,1976 and the Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act 1984; and failed to follow the instructions laid down by the central government on communal disturbances.

The Pehlu Khan case

An independent fact-finding mission found glaring gaps in police investigations of the case of the brutal lynching of Pehlu Khan, a Muslim farmer, at Alwar in Rajasthan in April 2017.

The lynching had been carried out by a ruling party-oriented group of self-styled gau-rakshaks (‘cow-protectors’) when the victim was returning home after purchasing cattle.

Earlier in 2015 at Dadri in Uttar Pradesh, cow-protectors had lynched a farmer named Mohammad Akhlaq on suspicion of storing cow meat at home.

Police investigations in both cases revealed the motivated doctoring of evidence to enable the culprits to get off the hook and escape judicial scrutiny and punishment.

Unusually, a central government minister took an active role in saving the culprits, affiliated to the ruling party, from coming under judicial scrutiny and punishment.

The ruling establishment not only remained silent but, in some cases, the guilty policemen were even lauded by the ruling elites.

Political mobilisation against the Muslims since the 1990s has been articulated by the ruling establishment. It gathered strength and led to the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, orchestrated violence against Muslims in Mumbai in 1992-93, followed by the apocalyptic violence in Gujarat in 2002.

The Vohra Committee report of 1993, dealt with the ‘criminalisation of politics and politicisation of crime’ and the nexus between politicians, criminals and civil servants were noted.

Causes of discrimination in criminal justice

A lack of political will and non-implementation of recommendations made by several reforms Commissions are among the main causes. Structural inequality and injustice in the social and political system too need mention.

Some practical steps:

1 - Amend the Constitution of India to include not just religious minorities but also national and ethnic, Indigenous and caste minorities (Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes) and their languages and cultures in a list of recognised minorities.

2 - Enact new law to prevent and punish crimes against the minorities, especially Muslims and Christians, on the lines of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act of 1989.

3 - Establish accountability mechanisms for the Indian police and politicians to end impunity.

4 - Implement criminal justice reforms of a far-reaching nature. All the penal laws, including the IPC, the CrPC, the Evidence Act and the Police Act need to be further reformed to suit the democratic, republican nature of the Constitution of India.

5 - Adopt the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, prosecutors, lawyers and judges.

6 - Adopt UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms; Standards and Norms in Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice.

7 - Establish special procedures of the UN Human Rights Council such as working groups on arbitrary detention and enforced and involuntary disappearances; a special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary and arbitrary executions, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment; and a standing invitation to the special rapporteur on the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Indigenous communities.

K.S Subramanian was a member of the Concerned Citizens Tribunal on Gujarat 2002 with former Justices Krishna Iyer, P.B Sawant and others. This paper is written in honour of Justice Sawant with whom he interacted and learned from during his work in the Tribunal. He retired from the Indian Police Service (1963 batch) as Director in the Union Home Ministry and also served as DGP Tripura