The Death of Raman Kashyap

The plight of India’s stringers

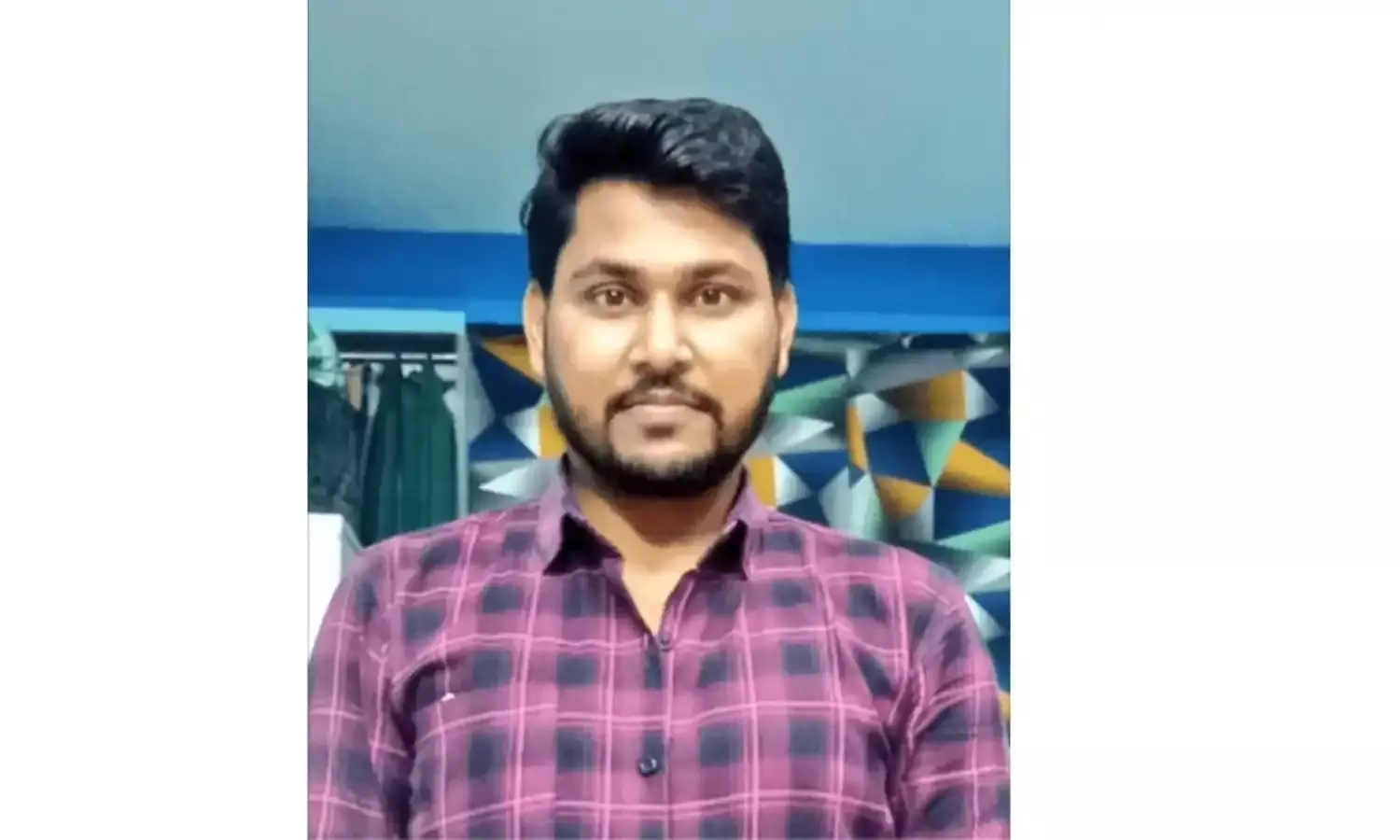

The death of journalist Raman Kashyap --- many on twitter are referring to it as the murder of journalist Raman Kashyap --is no small matter. He might be more famous in death than he was in life, but his passing has highlighted not just what is wrong with the system but what is becoming increasingly wrong with the media.

Kashyap represents the invisible journalist across India --- the stringer who works day and night to eke a living from his reports and is present where the more fortunate scribes fear to tread, allowing passion and work to drive him, and not greed or recognition. He is not greedy, having had to make do with very little in his life, and he does not seek recognition as he knows that the media organisations he contributes to will deny him even a tiny spot in the sun.

This has been the fate of stringers all along. Unrecognised and spurned by the ‘headquarters’, sending in snippets which were mostly discarded, and if important were covered by journalists on the regular pay roll with the stringer acting at best as a tour guide for those air dropped from above.

As journalists travelling across India we would seek out the stringers, the locals, who knew the politics and the dynamics of the districts they lived in better than any other. The invisible breed of journalists who are lucky if their news is even acknowledged and fortunate if they are paid for the few lines that do appear.

Raman Kashyap was a prototype. He was at the head of the farmers' stir, covering the protests from the ring seat as it were. In this case it meant walking with the farmers, talking to them, and reporting from the fields. Son of a farmer, and as subsequent videos and interviews with his family have revealed, poor where even the few hundred rupees he received as and when, being of great value to him and his family.

So Kashyap was amongst the group of farmers who were leaving the site of a successful protest against the Union Minister of state for Home Affairs at Lakhimpur Kheri. It was to be a peaceful, quiet walk back when suddenly two large vehicles came hurtling down the dirt path and smashed into the farmers from behind. Completely unaware they were literally mowed down, and amongst them was the young journalist who was returning secure in the knowledge that he had a good story, and more so as no other scribes had even bothered to turn up to cover the farmers protest. Mowed down or hit by a bullet subsequently has to be ascertained, but the fact that he is no more is inalienable.

Kashyap died, and in his death is the tragic story of our stringers. No media house, not even the one he mostly contributed to, recognised him. No one turned up for his last rites or paid respect to his family. Instead as his brother has said in a video interview, a television team visited the family and tried to make them change their version. And the irony is that even if his story had been accepted, he would have been paid no more than Rs 500 by the rich and powerful media house he contributed to. And yet like stringers across the country Kashyap was driven by a passion that the urban journalists have forgotten, and a commitment that made him walk the course for a story he believed in.

Earlier, and perhaps even today, many newspapers did not pay the stringers but just allowed them to keep a small percentage of the advertisements they could secure for the publication. So many of them would spend countless hours chasing the district authorities and local legislators for advertisements, knowing that their livelihood was dependent on this. Even so they would send in stories hoping to emerge from the hovel to a fully paid job. Not many succeeded, or succeed today for that matter.

Their news is invaluable as we learnt to recognise very early on in the job, Always hungry for a good in depth story it was these district stringers we hounded for ‘leads’. I still remember the big story that emerged from two lines sent by a stringer about the rape of a Dalit girl in a very remote village in Basti. The news got out only because her brother had got a job in a factory outside, and was more aware of his rights than those trapped in a medieval time frame back in the village. There are innumerable examples as these stringers work from the ground, and are hinged to rural and real India.

So there is a difference and a hierarchy, becoming increasingly rigid even though journalists are supposed to be in place to break these hierarchies. There is a difference in our response between the television journalist and the print or digital journalists, a difference between the english media and the regional media, a difference between the man and the woman journalist (a new fissure), between the brahmin and the dalit journalist, between journalists from different communities (also recently added), and then of course the regular scribe and the poor struggling stringer that has been present since times immemorial.

I remember on a former Prime Minister's abroad the anger amongst the language journalists about what they said was discriminatory behaviour on part of the officials accompanying him. Of tears shed for an English byline with the death of a regional journalist passing unnoticed in Delhi. Of stringers not getting bylines, and as I said often not being paid although their news became an idea for reporters in the main offices to work on. A never ending list…..