The Real Reason Why the Indian Diaspora Gave Rock Star Status to PM Modi

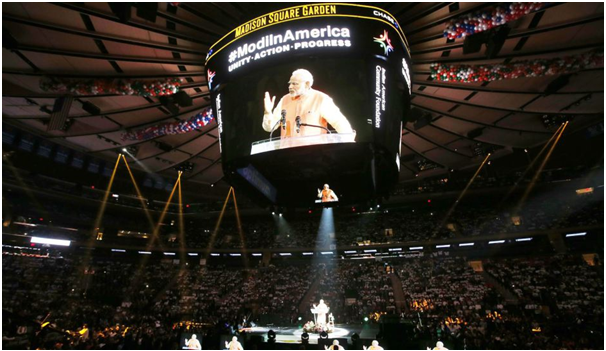

PM Modi at the Madison Square Gardens with screaming Indian-American fans

Prime Minister Modi’s rousing reception by Indian diasporics in advanced western countries--- U.S.A., Australia and Canada in particular—has been a constant refrain and cause for celebration in a number of media reports.

Given the Bharatiya Janata Party’s right-wing and corporate-friendly investor policies, has the intelligentsia in India seriously queried the reasons, characteristics, and consequences of this mass euphoria? The phenomenon of globalization by itself is insufficient to explain this massive upsurge in so far as a free-market provenance and exponential availability of communication media are concerned. These accoutrement of the twenty-first century geo-politics would go part of the way to solve the mystery of an attraction for FDI investments and the seductions of a large consumer market for foreign investors in particular.

However, quite apart from the economic and technological settings that favour affluent foreigner-enthusiasm for India, we need to focus on the political scenario or, in other words, the advent and impact of a neoliberal era in the much talked about “idea of India’’ in the present conjuncture. This particular tack of the tracing of the roots and flowering of a neo-liberal political ethos constitutes to my mind the key to the current Indian diasporic euphoria that we seek to explore.

Anthropologist Aihwa Ong in her book, Neoliberalism as Exception, 2006, writing basically about the predicament and tensions of socio-cultural changes in the political economy of Southeast Asia and East Asia, points to graded sovereignty and citizenship in the nation-states of this region. She talks about neo-liberalism as an exception and exceptions to neoliberalism. In this respect the contemporary Indian sub-continent is no exception.

Let us first look at the idea of a consolidated ‘territory’ of India. India’s post-independence leadership did not uncritically embrace the principle of sovereign territoriality. (In my discussion of extra-territoriality, I am indebted to Priya Chacko’s excellent review of Itty Abraham’s book, How India Became Territorial: Foreign Policy, Diaspora and Geopolitics, EPW, Feb. 14, 2015). Even Nehru, who was an advocate of self-contained territorial sovereignty for nation states and therefore is widely known to have advised the diaspora to stick to the nationality and nationalism of their countries of adoption, continued to lobby for the Indian diaspora of South Africa not on the principle of nationalism but on the basis of universal human rights. This was in line with his ambition for a world of territorial states which are nonetheless subordinate to a higher authority of a nation-state driven world order.

Subsequently, in the post Rajiv Gandhi period after regional leadership sorties in Fiji and Sri Lanka, the 1990s saw a decisive shift to embrace the Indian diaspora. As a transnationally oriented corporate class emerged, a new “global Indian subject” was produced through the extension of the Indian nation to include, in particular, a sub-section of the diaspora (termed non resident Indian, NRI), highly skilled immigrants who began to immigrate to Western countries from the 1960s and are seen to exemplify Indian success in the global economy. The push by a new transnationally oriented Indian capitalist class resulted in a shift towards extra-territoriality in government policy especially during the BJP rule. The creation of a new state celebration, Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (PBD), or Overseas Indian Day, a new category of overseas citizenship and, then, the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, were the immediate symptoms of this shift.

If we then tie this economic crisis of the 1990s with the social crisis brought about by the government’s decision to introduce reservation policies recommended by the Mandal Commission, as does Itty Abraham in his book, we get a complex explanation for the Indian government’s extraterritorial turn to the Indian diaspora than the more common explanation which rests on the potential economic contribution of the NRI to the globalizing Indian economy. The NRI diaspora, as a middle class, upper caste elite backlash to Mandal Commission reforms favouring lower classes became a “site of social stability and traditional middle class order for the reinstantiation of bourgeois hegemony”.

Is it any wonder, then, that the admirers of Modi in the developed western Indian diaspora are effervescent towards a utopian corporate developmental dream of an India today and tomorrow? And, mark it, the bourgeois affinities of NRI diaspora in U.S.A., Australia and Canada provides a complete foil to our working-class diaspora in the Middle East. The irony is that while the actual contribution of the Western-based diaspora to Indian coffers has been limited, a much greater contribution, in the form of remittances, comes from Indian migrant workers in the Gulf, many of whom are working-class, lower caste, or Muslim. These diasporic populations, however, have not been offered special privileges by the Indian government which, rather, has downplayed the harsh working conditions many migrant workers face in the Gulf region.

That there has been a neo-liberal ensemble between present day Indian government developmental policy declarations and the socio-economic make-up of Western-based diaspora is further highlighted when a mid-point in the economic hierarchy of Indian diasporics is taken into account.

If the affluent Western diasporics stand at the upper end of the extraterritorial neoliberal hierarchy and the Gulf migrants at its lowest end, those of the older vintage in the Indian Ocean region (South Africa, Mauritius, Malaysia), in the Pacific (Fiji), and the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Jamaica), hang uneasily at some mid-point. If we look at the struggles of this diaspora (earlier termed as people of Indian origin, PIO, to distinguish them from the NRI) their adaptation to the countries of adoption has been marked by ’challenge and response’, a valiant struggle against heavy odds. Most of them are the progeny of an exploited indentured labour class.

As to their attitudes towards India, most of them have a feeling of being sentimentally close to a ‘motherland’ rather than displaying what has been called a “commodified nostalgia “of the NRI (a phrase used by T.B. Hansen in his article in Himal 2002). Throughout the series of PBD celebrations, the representatives of PIO diaspora have complained of neglect and discrimination by the Indian authorities vis-a-vis the affluent NRIs. A question that may be legitimately raised is the step-fatherly treatment accorded by Prime Minister Modi towards these diasporics who are in Aihwa Ong’s terms “exceptions to neoliberalism” rather than “neoliberal exceptions” like the NRI.

Let me in conclusion sound a note of caution, if not warning, in relation to Indian diasporic bonhomie and euphoria in western countries as revealed in the recent Modi travels.

It is true that the conjunction of instant media coverage and Modi’s ambitious foreign policy jaunts has created the rock-star effect of the Indian Prime Minister’s rhetorical performances abroad.

For our own times this virtual simulacrum is close to what the sociologist Emile Durkheim in his book, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, 1961, called “social effervescence” when large congregation of aborigines physically gathered together to celebrate periodic rituals.

The media hype and explosion is a double-edged sword, however, when it comes to the fate of our diasporics in countries of their adoption and adaptation. The sad plight of Indonesian Chinese, who have been victims of state persecution at the hands of government authorities, has been commented upon by Aihwa Ong. She attributes the damning ill-will against Chinese diasporics in Indonesia squarely to the digital internet hype.

And, if the media exacerbations of communal Hindutva feelings in U.S.A. are anything to go by, the complicity of the social media in sustaining and giving rise to right-wing sentiments plays a similar role. Although as of now the past ban on Modi’s visit would seem to be a firmly forgotten chapter in Indo-U.S. diplomacy, who can guarantee that a communal sceptre of persistent right-wing neo-liberal, middle and upper class sentiments may not come to haunt today’s celebrants at home and abroad?