PM's Japan Visit: A Mixed Bag

PM Narendra Modi in Japan

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Japan has brought mixed results. While India and Japan can draw satisfaction on their expanding economic and strategic co-operation, there is considerable disappointment in India over the much-anticipated deal on nuclear energy not materialising.

During the visit, the two countries finalised deals that will see Japan investing over $35 billion in India over the next five years. Japanese public and private sector companies will provide funds and technology for rejuvenation of the River Ganga, development of smart cities, clean energy, building of bullet trains and transport corridors, procurement of liquefied natural gas, etc.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s five-day visit to Japan couldn’t have been better timed. Manufacturing today accounts for barely 15 per cent of India’s GDP; this share needs to rise by at least 10 percentage points in order to absorb a significant amount of the 12 or 13 million that join the country’s workforce every year. The key to this is attracting foreign direct investment, which is well encapsulated by Narendra Modi’s slogan “Come, Make in India”.

In this context, the Prime Minister has chosen the right country for his first major bilateral visit. Japanese companies are known for their just-in-time production approach, under which every original equipment manufacturer (OEM) seeks to source components and parts from vendors whose units are in the vicinity of its plant. Proximity and close coordination with ancillary manufacturers ensures supplies at the right time and low costs to the OEM. Over time, this leads to the creation of manufacturing clusters, as other OEMs are also encouraged to set up shop and, in turn, helps diversify the client base of the ancillary-makers.

The stimulus to manufacturing from such Japanese investments has been seen most clearly in Gurgaon-Manesar, where India has a host of units supplying pistons, crankshafts, fuel injection systems and other components to Maruti Suzuki’s car factories. One can point to similar Japanese-promoted manufacturing clusters that have sprung up elsewhere: Khushkhera-Bhiwadi-Neemrana in Rajasthan (Honda Motorcycles/Cars, Daikin, Hitachi, Nissin Brake), Bidadi (Toyota) and Narasapura (Honda) in Karnataka, and Jhajjar in Haryana (Panasonic, Denso). In general, Japanese manufacturing investments are taking place mainly along the Delhi-Mumbai and Chennai-Bangalore Industrial Corridors (DMIC/CBIC). A sprawling 1,600-acre township that will house more than 60 Japanese companies and have a residential zone is coming up south of Chennai, to tap into the growing Japanese interest in Tamil Nadu as an investment destination.

The most useful by-product of Modi’s visit could be to put implementation of the DMIC/CBIC projects in his government’s top priority list. Modi has, in fact, announced setting up a special management team in the Prime Minister’s Office to facilitate Japanese investments. He has even proposed that this team have two nominees from Japanese industry.

There is no doubt that Japanese investments can play a huge role in realising India’s unfulfilled manufacturing potential. Rising labour costs and increasing difficulties — political and otherwise — in doing business in China has made India more attractive than before for global manufacturers. It was no accident that Hitachi’s board meeting in New Delhi, the first held by the company outside Japan, was accompanied with an announcement of its India strategy. But there is a lot of work required to translate growing interest into big investment. Modi has promised a red carpet instead of red tape, but his government will have to follow this up with action for better delivery.

The range of issues on which the two countries will work together is indeed remarkable and India’s ramshackle infrastructure will surely benefit from infusion of Japanese technology, funding and expertise. Defence co-operation is poised to grow too and the coming years could see the Japanese selling India amphibious aircraft, for instance.

Such aircraft will enable the Indian Navy to insert troops even in areas where there are no landing strips. An agreement is expected to see transfer of technology too as the amphibious aircraft could be manufactured in India, reducing our dependence on foreign manufacturers for defence hardware.

Indian leaders and diplomats need to understand that while Japan is an important partner, China is our neighbour, a country with which we share a long, disputed border. Smart diplomacy involves improving ties with both Japan and China, not siding with one while ruffling the feathers of the other or even choosing between them.

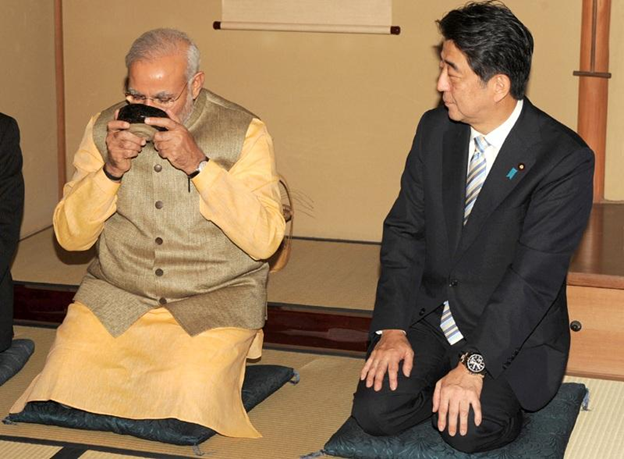

Modi got on well with his Japanese counterpart, Shinzo Abe. Their interaction was punctuated with bear hugs and bonhomie. However, an agreement on civilian nuclear co-operation proved elusive. Although the two sides downplayed the differences by claiming ‘improved understanding’ on the issue, it is evident that Japan is still a long way from sympathising with India’s concerns.

Despite the bonhomie, India and Japan failed to break the ice in ongoing talks on a nuclear deal between the two countries. The two sides signed a statement of intent to continue talks on the nuclear deal, officials said after summit talks between the two leaders in Tokyo today.

The Japanese PM said there had been, "important progress on nuclear cooperation in the last few months. I was able to have frank discussions with PM Modi on this issue and deepen understanding on both sides." Talks on a deal have been stuck on Japan's insistence on a clause that India won't test again and will allow more intrusive inspections of its nuclear facilities to ensure that spent fuel is not diverted to make bombs.

Sources say the Modi government had hoped to lure investment into its $85 billion market while addressing Japan's concerns. India has been pushing for an agreement with Japan on the lines of a 2008 deal with the United States under which India was allowed to import US nuclear fuel and technology without giving up its military nuclear programme. India, which sees its weapons as a deterrent against nuclear-armed neighbours China and Pakistan, has sought to meet Japan's concerns.

A civil nuclear energy pact with India would give Japanese nuclear technology firms such as Toshiba Corp and Hitachi Ltd access to India's fast-growing market as they seek opportunities overseas to offset an anti-nuclear backlash at home in response to the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident.

India operates 20 mostly small reactors at six sites with a capacity of 4,780 MW, or 2 percent of its total power capacity, according to the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited. The government hopes to increase its nuclear capacity to 63,000 MW by 2032 by adding nearly 30 reactors.