Memories of Sinhalese Militancy Resurface, Violence With Impunity

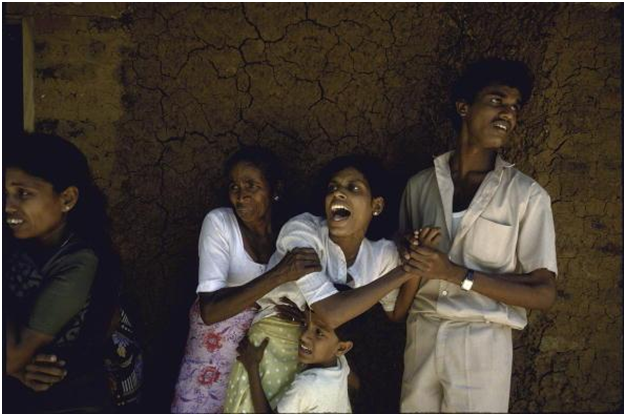

Terrified women and children after Army took their husbands for interrogation after land mine blasts

COLOMBO: Last week there was an unexpected focus on events that took place 25 years ago and which had appeared to have fallen out of public memory. This was the Sinhalese militancy led by the JVP in a three year period of terror that gripped most of the country and excluded only the predominantly Tamil-speaking North and East. The general belief is that about 60,000 people perished in the period 1988-90. But there is no certainty about the figure.

The numbers killed by the JVP were counted by the government at that time which gave precise numbers. These included 487 public servants, 80 of whom were bus drivers, 30 Buddhist monks, 2 Catholic priests, 52 school principals, four medical doctors, 18 estate superintendents, 27 trade unionists, 342 policemen, 209 security forces personnel and family members of 93 policemen and 69 service personnel. But the numbers killed by the government side were not counted or shared.

The overwhelming present local and international focus has been on the final phase of the war against the LTTE and this has taken the country’s attention away from those terrible events. But suddenly the tragic past was brought back to life. The media ran several stories on what happened those days. In particular there was a vivid description of the last hours of the JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera when he was held in captivity by the government forces. It showed how he was interviewed by the political and military leaders of that time who had been at the receiving end of JVP violence. It showed how he was subjected to their violence. It showed how people can act when they hold absolute power of life and death over those who have been their enemies, and why the laws cannot be silent even in a time of war, or when the war has just been won.

The re-emergence of accounts of the killings and massacres of the JVP insurrection in the public eye, 25 years later, is a reminder that the past can never be ignored and can spring up at any time. Just as the country is heading for a decisive presidential election, there is reason for the past to be revived due to political reasons.

The main protagonists 25 years ago were the UNP which formed the government at that time and the JVP, which today are trying to get together in an opposition alliance against the present government. The publicity being given to the events of the past have put these two parties in an unfavourable light. However, another important message that comes as a by-product is that the tragedies of the past do not go away by themselves. The wounds of the past need to be consciously cleansed of untruth and healed through justice, development and reconciliation.

After the JVP insurrection of 1988-89 there was no action taken against those who were accused of human rights violations. Instead all was put aside and buried along with the past. The same practice appears to be the desired one after the end of the LTTE war also. But as the continuing international agitation on the issue of war crimes in Sri Lanka continues to increase, with no sign of getting less, there is a need to think newly about how best to deal with the situation. Instead of which the government is getting into an escalated conflict with the UN system where it cannot possibly prevail. The government’s position has been that the UN investigation in to war crimes is intrusive, biased and against the national sovereignty of the country and while the government will cooperate with the UN system in general, it will not do so with regard to the war crimes investigation.

However, the Office of the UN Human Rights Commissioner is one of the many UN institutions that have been set up to further the overall goal of world peace and stability for which the UN was set up in the aftermath of the Second World War, which led to the loss of millions of lives and the destruction of a significant section of the world’s heritage. The UN system cannot permit one of its key institutions to be weakened or undermined due to the actions of one of its 193 member countries. When the Sri Lankan government rejects the UN High Commissioner’s statement using strong language which may meet the expectations of the electorate and of the majority of Sri Lankan people, it is challenging an important component of the UN system.

Previously it was believed by many in Sri Lanka, including by those in the government, that Sri Lanka’s problem at the UN was being caused if not made worse by the actions of the previous Human Rights Commissioner, Navanethem Pillay. It was believed that although her citizenship was South African, her Tamil ethnicity had made her biased against Sri Lanka. Therefore she too became a part of the global anti-Sri Lanka Diaspora in Sri Lankan eyes and her departure from office was expected to change the UN’s attitude to the issue of accountability for war time problems of human rights. But this has not happened. The new Human Rights Commissioner is even stronger in his position that Sri Lanka must address the issue of accountability. But it is not only to the international community or to the UN that the government needs to give answers.

In the past week I took part in discussions and seminars in the North and East on the issues of post-war healing and reconciliation amongst communities. In the meetings I attended I saw at first hand the powerful sentiments of people who have lost their loved ones and have found no answers forthcoming from the government. There was a mother who said that she had surrendered her son to the military at the end of the war. She wanted to know what had happened to him. She still had hope he was alive. She said other young persons who had been surrendered like her son had returned, but she said that they did not say what had happened to her son, and would not talk about the past. She said she had even been to the army camps in the East to look for him, although she was from the North and her son was surrendered in the North. She had also been to the Fourth Floor of Police Headquarters in Colombo. She would go anywhere to find her son. She had not found him, but she still had hope.

At none of these events was there interference by the military or government officials. However, some of those who participated said they noted the presence of unidentified persons who took photographs and went away. Some of them also said that when they tried to organize similar events, the security forces in those areas wished to know what was happening and why. This may not be done with the intention of disrupting the activity, but rather to know what is going on. But the psychological climate is such that even this information gathering can create unease in a population that continues to live in the memory of the war that had so cruelly shattered their lives.

It is not only to the UN investigators that the government needs to give its answers, and it is not only about the LTTE war. The Sri Lankan state itself needs to give answers to its own people too for events that go back in time 25 years ago. A new electoral mandate will not negate the need to provide answers. The issue of human rights and war crimes that include the JVP period, as much as the last phase of the LTTE war, needs to gone into, the truth ascertained and reconciliation be achieved, as it was in South Africa. It is better that these issues are addressed sooner rather than later for they will not go away, even as the killings of the JVP period have not gone away. Obtaining the support of friendly countries like India, Japan, Korea and South Africa, as the government appeared to be doing for a while, and persuading the opposition to join in this, to achieve a balance between the imperatives of Truth, Justice, Development and Reconciliation that span the longer period is the best possible thing to do in the circumstances. It can even justify postponing the envisaged snap Presidential election for two years, as constitutionally permitted, to find an awareness creation, reconciliation and healing process, and agree on a new political system that will ensure that the violent tragedies of the past where impunity and lawlessness rode high are never repeated.