Pakistan Revives Non-Islamic Past To Shed Image of Intolerance

India turns majoritarian

While the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is beginning to revive its non-Islamic past and is proudly displaying artifacts related to its Buddhist and Sikh heritage, “secular” India has started obliterating its Islamic past and is trying to re-establish and highlight the Hindu heritage instead.

Pakistan is trying hard to shed its image of an intolerant Islamic country and is assiduously preserving artifacts relating to its ancient Gandharan-Buddhist cultural heritage. But the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled Center is making a serious attempt to “saffronize” medieval history which is largely Islamic.

The Yogi Adityanath-led BJP government in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest State, is showing the way to the rest of the country to change the Muslim names of places.

“Allahabad”, thus named in the 17th Century by Mughal Emperor Shahjahan, has now been renamed “Prayagraj” with virtually no one protesting against the blatantly communal move.

An official statement released by the UP government hid the real “Hindutwite” intention behind the name change and asserted that a board of researchers had perused documents and found that people had been under a “delusion” that Allahabad had been “Allahabad’ all the while.

“There was a delusion that the place was always called Allahabad and so the revenue board suggested that in order to correct this delusion, it would be reasonably legal to change the name to the original name,” the statement said.

Indeed, before the advent of Mughal Emperor Shahjahan, the area was known as “Prayagraj” being the most prominent of the 14 Prayags in India. However, the renaming was clearly motivated by the government’s Hindutva political agenda.

Given the extent of BJP’s hold over Hindu India, the tendency to change names with an Islamic or Muslim-era tint would continue and become the norm as changing British-era names to Indian names had caught on in the earlier “Indian” nationalist period.

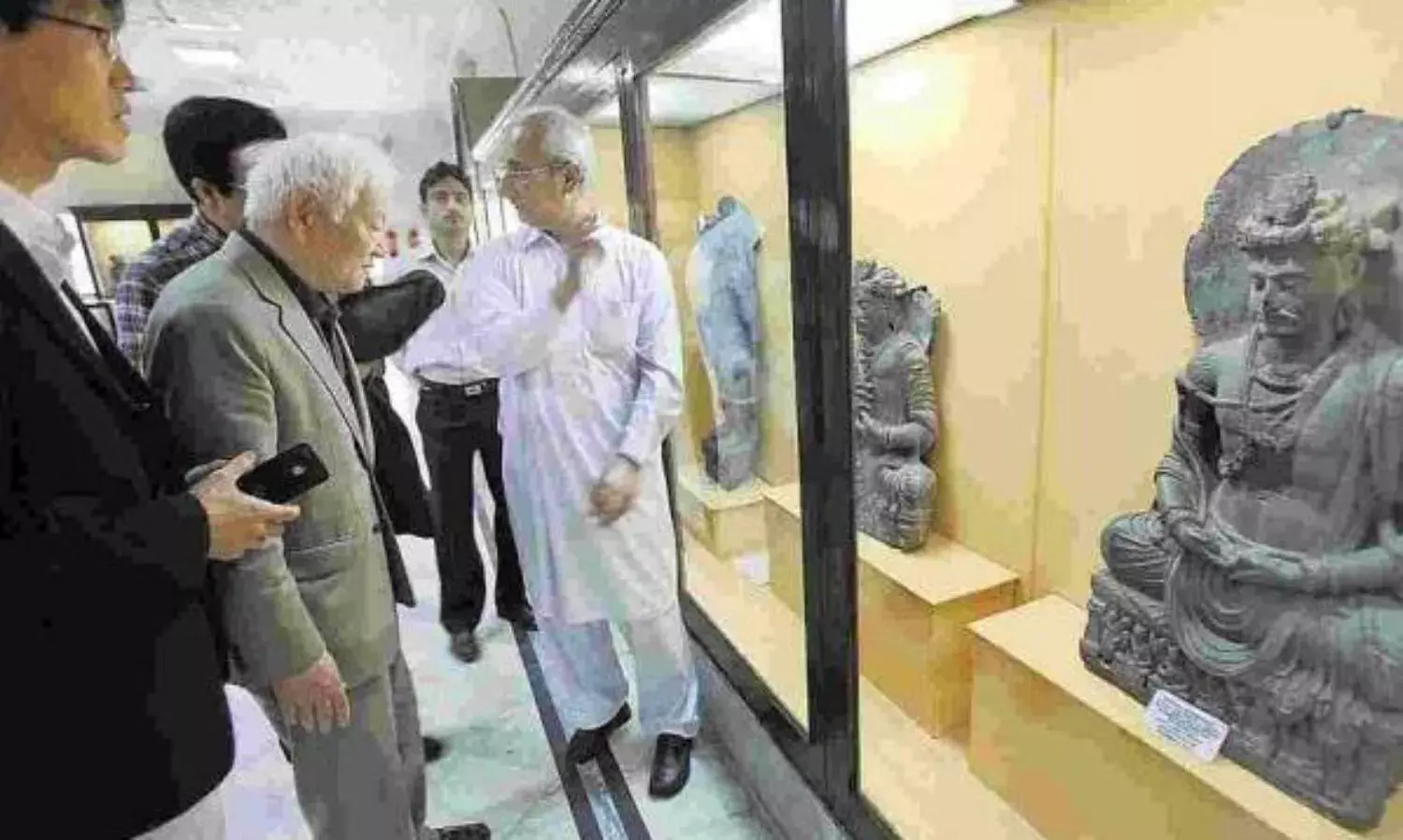

But strangely enough, there is an incipient but noticeable trend in Islamic Pakistan to revive and display the country’s non-Islamic past.

For about a decade now, Pakistan has been trying hard to live down its sectarian image and portray itself as a tolerant society equally proud of its Islamic and pre-Islamic Hindu, Buddhist and Sikh past.

Pakistan is now angling for foreign tourists, especially from Buddhist countries, so that they may savor the delights of its multi-cultural and multi-religious past and bring much needed dollars into the country.

It is also trying to revive the ideology of its founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who immediately after securing a “homeland” for the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent, pledged to make Pakistan a non-sectarian haven for all citizens irrespective of their faith.

In a speech made in 1947, Jinnah told the minority Hindus, Christians, Sikhs and Parsees: "You are free to go to your temples; free to go to your mosques, or any other place of worship in this Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the State."

However, Pakistan became an lslamic State in 1956. The Shariah law imposed by President Zia-ul-Haq in the 1970s triggered open persecution of religious minorities. Radio Pakistan went to the extent of destroying the recording of Jinnah’s 1947 speech on the accommodation of minority communities.

After 1971, Pakistan’s students were not taught the pre-Islamic history of the country. “ Instead, history books started with the Arab conquest of Sindh and swiftly jumped to the Muslim conquerors from Central Asia,” points out Nadeem F.Paracha in Dawn.

However, quietly, Pakistan’s small community of archeologists had kept the torch of tolerance and liberalism burning.

Dr.Ahmad Hasan Dani, who was one of Pakistan’s earliest archeologists, had come to the field with a gold medal in Sanskrit studies from the Banaras Hindu University in India.

He took a fancy to Buddhist sites in the Gandhara region of North Western Pakistan. The Gandhara region had been a cradle of Hindu and Buddhist civilizations in the early Christian era. Its impact is evident even today as the image of the Buddha we have today is actually a Gandharan construct.

The land of Gandhara has been well known since the reign of Cyrus the Great (558 – 528 BCE). The region comprised the present day Peshawar and Swat Valleys in northern Pakistan and a part of Afghanistan. There was a confluence of cultures and religions in Gandhara. It included ethnicities such as Greek, Mauryan, Scathian, Parthian, Kushan, and White Hun.

Dr. Dani later became External Director of Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations at the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad; set up the Archaeology Department in the University of Peshawar; established the school of social sciences in Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad; and inaugurated the Islamabad Museum. An appreciative Pakistani government bestowed the Hilal-i-Imtiaz award on him.

There are 6,000 historical/archeological sites in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Of these, 2,000 sites belong to the Gandhara Civilization. But many of these have virtually disappeared due to local vandals ,plunderers, antique thieves and smugglers.

The rise of the Pakistani Taliban, an offshoot of the Afghan Taliban of the early 2000s, led to a systematic destruction of Buddhist antiquities in the Gandhara region.

Antiques were dug up and sold to international smugglers. Villagers were told that they would earn spiritual merit if they destroyed these artifacts or idols (or even sold them illegally). Over 20,000 Gandhara art works are now said to be abroad.

In 2007, a Swat valley schoolteacher, Osman Ulasyar, was arrested and put on trial by the Taliban on charges of preserving the “symbols of infidelity.” His crime was constructing a 300-feet protective wall to safeguard a Buddhist stupa court. He had sold his car to pay for the wall construction.

While the Taliban has been routed in Swat and the threat is over now, the archeological sites there face new threats from the land mafia and artifact smugglers. Negligence of the government and the lack of awareness among people about the region’s history impede protection, Ulasyar says.

To prevent looting, the government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province has set up eleven museums. There are now 16 “protected sites” registered with the archaeology and museum department. Under the antiquity laws, no construction is allowed within a 200 feet distance of a historical sites, though this rule is beached in many places.

Come 2012, there was a turning back in governmental circles from Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamic zealotry. The Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (PBC), which had earlier destroyed a recording of Jinnah’s speech on the rights of the minorities, sought from All India Radio a copy of it.

PBC’s then Director-General, Murtaza Solangi, had said: “This speech is very important for people who want to direct the country to the goal of a modern, pluralistic, democratic state.”

As years rolled, Pakistan began using its Buddhist past to build bridges with Buddhist countries like Sri Lanka.

In 2006, the Pakistan High Commission launched Sri Lankan Professor J.B. Dissanayake’s Sinhala translation of Pakistani academic Ahmed Hassan Dani’s 1992 work Gandhara Art in Pakistan.

The following year, the High Commission helped translate into Sinhala, Ihsan H. Nadiem’s Buddhist Gandhara-History, Art and Architecture. In 2010, at the request of the then Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, Pakistani President Asif Zardari sent the Buddhist relics of Gandhara for exhibition in Sri Lanka.

In June 2011, to mark the 2600th anniversary of the Buddha's enlightenment, the government of Pakistan handed over two Buddhist relics from museums in Pakistan to officials from Sri Lanka. In January 2016, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif visited the holiest Buddhist shrine in Sri Lanka, the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic at Kandy.

In May of the same year, by invitation of the Pakistani government, a 43-member delegation of Sri Lankan ministers, monks, scholars, and journalists visited Pakistan to attend the first-ever Pakistani Vesak Festival at Taxila.

Recently, the Pakistan High Commission revamped its website which, besides being comprehensive in its coverage, also stressed Pakistan’s links with Buddhism and Sikhism.

The Pakistan government has now sought Sri Lanka’s cooperation in developing its Gandharan and Buddhist Studies Center located in Taxila (the ancient Taksasila) near Islamabad, set up in 2017.

The proposal for cooperation was mooted at a meeting between the Pakistani High Commissioner in Sri Lanka, Dr.Shahid Ahmad Hashmat, and the Sri Lankan Minister for Foreign Affairs,Tilak Marapana, on October 9.

The Center for Gandharan and Buddhist Studies is pushing for grants to do research on the history of Gandhara. The idea is to revive the spirit of the ancient University of Taxila. “Although a lot of archeological and historical studies has been done on the Gandhara region, a lot remains to be done,” the Center’s website says.

To facilitate research on Buddhist remains and understand their significance, Pali and Sanskrit will be taught at the Center. It is in the sphere that the Center would need Sri Lanka’s help as Sri Lanka has Buddhist research institutions and Pali is taught in the universities.