In Sri Lanka Cartoonists Are Not Killed, They Just Disappear

In Sri Lanka cartoonists just disappear

COLOMBO (IPS): Scenes from the brutal shooting of 12 journalists with the French satirical weekly ‘Charlie Hebdo’ have monopolised headlines worldwide ever since two men opened fire in the magazine’s Paris office on Jan. 7.

Millions have marched in the streets against what is widely being billed as an attack on free speech, and the work of the magazine’s cartoonists has gone viral.

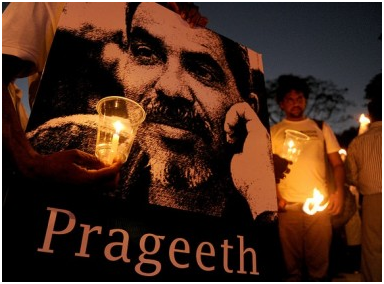

Several thousands miles away, in Sri Lanka, a different attack on press freedom has not received even a fraction of the attention. Perhaps because, in this particular tragedy, the leading character was not killed. He simply vanished without a trace.

“One sure way to reverse the dangerous trajectory Sri Lanka has been going down during the past decade is to seriously address the pleas of those like Sandhya Eknaligoda, whose husband Prageeth remains missing five years on [...]." -- Sumit Galhotra, Asia Researcher for the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

The last time anyone heard from Prageeth Eknaligoda was on Jan. 24, 2010. Just after 10 p.m. he called to inform his wife, Sandhya, that he was on his way home from the office. He never arrived.

From local police stations all the way to the United Nations in Geneva, she has searched for answers as to his whereabouts, but found none.

Rights groups like Amnesty International believe the authorities played a role in his disappearance, while neighbours report seeing an unmarked white van parked outside his house the day he went missing – a vehicle widely associated with enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka.

A cartoonist and columnist for Lanka eNews (LEN), Eknaligoda had long used his pen to draw attention to corruption, human rights abuses and eroding democracy in Sri Lanka.

One of his most widely shared images depicts the back of a half-naked woman facing a gang of laughing men. Scratched on the wall behind her are the words “Preference of the majority is democracy”, which some commentators claimed was a reference to the powerlessness of minorities in a largely Sinhala-Buddhist country.

He also turned his sharp pen to the issue of education, sketching out in glaring detail the impact of a weak school system on the youth, including one cartoon that depicted the tragic suicide of a student at a leading girls’ school in the capital, Colombo.

In a country that is ranked fourth – between the Philippines and Syria – on the Impunity Index compiled by the leading media watchdog Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), it was perhaps only a matter of time before Eknaligoda was forced to answer to the powers that be.

But because there is no evidence to show he suffered the same fate as the 19 Sri Lankan journalists who have been killed in cold blood since 1992, Eknaligoda is not included among those who paid with their lives for their writings.

Because his body was never found, there is no gravesite around which to gather to mourn his death. In fact, former Attorney General Mohan Peiris told a United Nations Committee against Torture in 2011 that Eknaligoda was still alive and living in a foreign country – a statement he later retracted.

As far as the family is concerned, disappearance is a fate worse than death. In an interview with IPS in 2012, Sandhya Eknaligoda explained, “Not knowing where your loved one is, that is mental torture. And it is worse than physical torture, where at least the world can see the marks of your suffering.”

New government, new hopes

On Jan. 7, as news of the Charlie Hebdo massacre reached heads of state around the world, Sri Lanka’s then-president Rajapaksa was among those to immediately offer condolences to the victims’ families.

Those who have closely followed Eknaligoda’s case called the statement hypocritical, given the government’s alleged indifference to a free press in Sri Lanka.

So when Rajapaksa was ousted at the Jan. 8 presidential election, replaced by his former party secretary Maithripala Sirisena, experts and activists began, tentatively, to hope for accountability.

“Maithripala Sirisena’s stunning win marks an opportunity for Sri Lanka to improve the climate for press freedom,” Sumit Galhotra, Asia researcher for CPJ, told IPS. “While he has pledged to eradicate corruption and ensure greater transparency, we will be watching closely to see if he follows these verbal commitments with concrete steps.

“One sure way to reverse the dangerous trajectory Sri Lanka has been going down during the past decade is to seriously address the pleas of those like Sandhya Eknaligoda, whose husband Prageeth remains missing five years on and to begin combating the culture of impunity that has flourished in the country when it comes to anti-press violence,” he added.

Among a long list of atrocities that the journalistic community has suffered was the assassination of Lasantha Wickrematunge in broad daylight on Jan. 8, 2009. Founder-editor of the major English-language weekly, the Sunday Leader, Wickrematunge was an outspoken critic of all forms of abuse of power and human rights violations.

Addressing a crowd of some 50 people who gathered at his gravesite on the morning of the presidential poll exactly six years after Lasantha’s death, his brother Lal Wickrematunge called attention to the failure of the “numerous squads assigned to handle investigations into the murder [to make] any headway.”

Now, as the new government assumes office, activists say there will be a renewed push for justice.

It is still early days, but already there have been some positive steps.

“Some of the websites that were blocked like TamilNet and Lanka eNews are accessible now, and these are good signs,” Ruki Fernando, a prominent grassroots activist here, told IPS.

“But there are a number of cases, like Prageeth’s, Lasantha’s and many, many others – including numerous cases against the [Jaffna-based Tamil language daily newspaper] Uthayan – that need to be expedited.

“That doesn’t mean that Lal [Wickrematunge] or Sandhya [Eknaligoda] are asking for political favours,” he asserted. “All they’re asking is that the normal course of justice, which was been obstructed so far, be allowed to proceed in an independent manner without political interference.

“These are things we expect from the new regime in its first 100 days,” Fernando stated. “Until they are implemented, I don’t have much confidence – I only have hope.”

(INTER PRESS SERVICE)