India Supports Sri Lanka Against UN Investigation on War Crimes

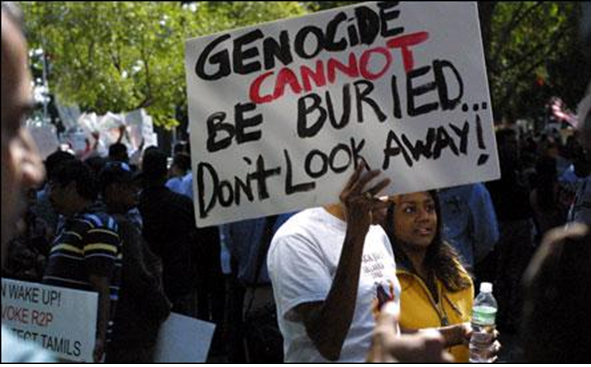

The story that refuses to go away: Protests at the UN against the killing of Tamils

COLOMBO: The lack of unanimity within the UN Human Rights Council on the issue of the investigation into Sri Lanka continues. The government has continued to stick to its position that it will cooperate with the UN in general but not with the investigation into war crimes.

The Indian government’s representative has queried how the investigation can go ahead without the cooperation of the Sri Lankan government. He has urged transparency in the investigation process noting that “The composition of the OHCHR investigation team, its work methodology and sources of funding have also not been shared with the Human Rights Council.” This Indian position is a strong criticism of the investigation as currently being adopted by the UN. The findings that come out of a process that is problematic will be liable to be challenged in the future.

The absence of transparency in the process is a problem. Except for the coordinator of the investigation team, the identity of the rest of them is unknown. This is not a transparent process and it will not lead to the confidence building necessary for acceptance within Sri Lanka. It adds to the perception of an international conspiracy that the government has been alleging. The inability of the UN system to deal with gross human rights violations in other parts of the world, in particular the Middle East, where strategic Western interests are at stake, is indicative of a selective targeting of Sri Lanka, which is the stuff that conspiracy theories are made of. This point was made by President Mahinda Rajapaksa when he addressed the 69th Sessions UN General Assembly last week.

The President stressed the need for the UN to gain the confidence of the international community as a whole and pointed out that one of the essential requirements for this purpose was “consistency of standards across the board without any perception of selectivity or discrimination.” Sri Lanka has also been able to get together a group of 22 countries led by Egypt to take a position that the UN investigation is “unwarranted especially in the context where the country is implementing its own domestic processes.”

However, the Western countries continue to support the UN investigation. If there was an expectation on the part of the government that the replacement of the former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navanethem Pillay by anyone else would lead to a relaxation of UN pressure, this has been shown to be mistaken. There has been no relaxation. On the contrary, the new UN High Commissioner Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein has issued an update on the current situation in Sri Lanka that is not any different in either tone or spirit from the ones by his predecessor in office. The new Human Rights Commissioner has repeated the earlier call by Ms Pillay regarding the most important matter of them all. This is regarding the expectation that “the government will initiate a comprehensive truth seeking process, as recommended by his predecessor and echoed by the UN Human Rights Council.”

The UN Human Rights Commissioner’s report makes a strong critique of the ongoing governmental investigations which are expected to be directed towards ascertaining the truth of what happened during the war years. It says that the expanded mandate given to the Commission on Missing Persons would require an extra allocation of resources, but whether this has been done or left undone is not clear. It also says that the role to be played by the five international advisers is also not clear. The report also quotes from a report by families of the missing persons that “harassment and pressure by police, military and intelligence prior to and at the time of the hearings of the Commission on Missing Persons, which prevented some of them from giving evidence.”

The UN High Commissioner has also said that he “has been shocked at the ongoing campaign of threats, harassment, intimidation and reprisals by both the state and non-state actors since March against civil society groups, human rights defenders and victims’ organizations, including those who might support or engage with the international inquiry.” The examples given include the forcible break up of meetings of families of the missing persons , intimidation of lawyers who are taking up cases on behalf of victims and the attempt to prohibit NGOs from engaging with the media to supply them with information.

These governmental efforts to suppress the investigations into the past lead it to over-control the whole of society using the security forces and put it into a state of fear. The effort to control civil society, by using the security forces to engage in surveillance and to prevent public demonstrations, causes resentment. This makes a bad situation worse. It can even reach absurd proportions. Former civil servant, and Government Agent of Jaffna, Dr Devanesan Nesiah has shared his misgivings about how the government handled the memorial service for Dr Rajini Thiranagama who was killed by the LTTE 25 years ago for her human rights work. The organizers of the event were sent from pillar to post in finding a venue, with both the university where she once taught and the public library refusing to give them space for the event.

In a commentary on the event Dr Nesiah wrote “It was expected that with the LTTE eliminated from the Island and the IPKF gone, the commemoration would go more smoothly than 25 years earlier. It was not so. In Jaffna, as far as Democracy and Human Rights were concerned, there has clearly been regression, not progression…An unpleasant feature was the presence of few strangers, obviously neither participants nor journalists, who took photographs of the participants and recordings of the speeches and seminars. It was clear to everyone that they were security officers, though none of the proceedings were at all subversive.” This is evidence of a mistrust of civil society that is bordering on paranoia if not a desire to control due to fear of the consequences of losing control.

At the UN Human Rights Council, the Indian delegation took the view that “it is desirable for every country to have the means of addressing human rights violations through robust national mechanisms. The Council’s efforts should be to provide technical assistance to them to develop the necessary institutions for this purpose. We believe that engaging the country concerned in a collaborative and constructive dialogue and partnership is a more pragmatic and productive way forward. This is the approach that was envisaged by UN General Assembly resolution 60/252 that created the HRC in 2006, as well as the UNGA resolution 65/281 that reviewed the HRC in 2011.”

Instead of being at loggerheads with civil society and treating it as an enemy, to be monitored and suppressed, the government needs to enlist the support of civil society to face the challenges posed to it by what happened in the past. For a positive engagement to occur, the government’s legitimacy that comes from having a democratic mandate by virtue of winning elections needs to be respected. At the same time the universal values and international standards that are espoused by civil society groups also need to be respected. Both of these are essential components in taking Sri Lanka from its divided past to a united future. If this is achieved, India’s and other like minded countries support for Sri Lanka to solve its problems would bear fruit.

The government may have been hoping that its initiative to bring down five international lawyers, some of whom are eminent in their chosen fields, to be independent experts in its Missing Persons Commission would bring the ongoing UN investigation to a halt. The government would also have been hoping that the advice tendered by the five experts would have negated the need for a different and more comprehensive truth seeking process. But the thrust of the UN Human Rights Commissioner’s report has to be dealt with, and it is very substantially a critique of the government’s approach to human rights in general and to investigating the past in particular. The way forward for the government would be to strengthen its national (domestic) process of truth seeking and accountability by bringing in the opposition political parties and civil society so that it is truly a national effort.