Can Kabul Provide Security For The TAPI Project?

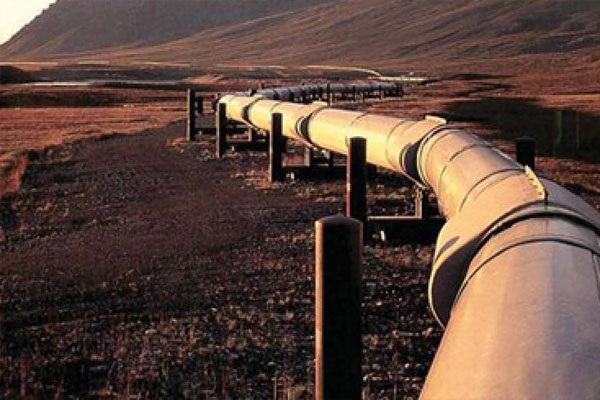

On December 13, 2015, the leaders of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India gathered in the Turkmen city of Mary to lay the foundation of the long-awaited gas pipeline famously known as TAPI – named after the participating nations. The ambitious 1, 814 kilometer pipeline is expected to cost around $10 billion and plans are for it to be operational by 2019. The TAPI pipeline, to be built by a consortium led by Turkmenistan’s Turkmengaz, will originate in Turkmenistan and flow through some of the most insecure parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan and into India. This ambitious project described by Afghan president Ashraf Ghani as reestablishing ties as old as a million years “ruptured” by the Soviet invasion, will have a capacity to carry 90 million standard cubic meters a day (mmscmd) gas for a 30-year period. India and Pakistan would get 38 mmscmd each, while the remaining 14 mmscmd will be supplied to Afghanistan.

The deal is the product of many rounds of talks between the leaders of these countries since collapse of the Taliban regime from power in late 2001. The leaders of the participating countries made promising statements with regards to the successful implementation of the project, which is believed to bring peace and economic prosperity to these countries.

In the words of Turkmen President Berdimuhamedov, “TAPI is designed to become a new effective step towards the formation of the modern architecture of global energy security, a powerful driver of economic and social stability in the Asian region”. India’s vice president Hamid Ansari said it was “the first step to the unification of the region” while the Afghan president Ashraf Ghani highlighted that they were “committed to the stable development of the entire region” [and if everyone cooperated it] will develop in an active and stable manner”. The Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif stated that the project “will help promote peace and trade amongst the regional countries”.

So far so good. These statements were heartwarming and seemingly opened a new chapter of cooperation and harmony among hostile nations such as India and Pakistan or Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, there are many unanswered questions and unresolved security problems on the Afghan--Pakistan territories. The insurgents who are hostile to the implementation of this project remain an existential threat, especially on the Afghan soil. This threat raises questions: can the Afghan government provide security for the pipeline? Will Taliban allow this pipeline to pass through their controlled areas without getting any monetary benefits?

The answer to these questions, one would argue, is dependent on the level of cooperation and commitment from the Pakistani Army. It is an open secret that the civilian government in Pakistan is subservient to the army and the Pakistani army calls the shots when it comes to important foreign policy decisions. Given the fact that India is involved and could be the biggest benefactor of the project if Afghanistan takes only 1.5-4mmscmd against the original agreed 14mmscmd with the remaining going to India, the Pakistani Army will not be happy to see its archenemy reap the maximum benefit. Hence, they will make sure to sabotage the project through their proxies on the Afghan soil. The Afghan and Indian governments have, time and again, blamed the Pakistani security apparatus for harboring and using militants as an instrument of its foreign policy against the two countries.

There is no doubt that the TAPI project will bring about economic development and prosperity to all participating countries and the leaders were immensely excited about the landmark deal. However, there are doubts whether the pipeline will come into fruition. History suggests otherwise. In late 1997, the California-based oil company, Unocal, planned to build a similar gas pipeline through Afghanistan. The Unocal officials were negotiating with the Taliban regime to help build the pipeline and they would get between 50 to 100 million dollar a year in transit fees.

However, a year later the security situation started deteriorating in Afghanistan. A group of Al Qaeda operatives bombed United States (US) embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. As the US government started launching cruise missile strikes against Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan in retaliation for the bombings, Unocal called off the project arguing that in the absence of a broad-based government in Afghanistan, implementation of such projects is not possible.

Bearing this argument in mind, Afghanistan once again is facing a similar threat. Insurgents are gaining more grounds, especially in the areas where the pipeline is supposed to pass. The writ of the central government is decreasing in the areas along the Pakistani border and there is no willingness on the Pakistani-security establishment to stop funneling assistance to the insurgents in Afghanistan. So long as such a love affair continues between the Pakistani Army and the Taliban, TAPI project is doomed to failure. We will witness insurgent groups blowing up the pipeline on multiple fronts and causing havoc. However, if it was a military government in Pakistan and a military ruler made the promise of cooperation and not Nawaz Sharif, then there was hope for the pipeline to be successful. Now that there are two opposing players in Pakistan, who do not see eye-to-eye when it comes to the army’s “strategic depth” policy, cooperation between these countries is far from real. TAPI will remain as a plan on paper for many years to come.