Sri Lankan Government Prepares to Pick Up The Gauntlet

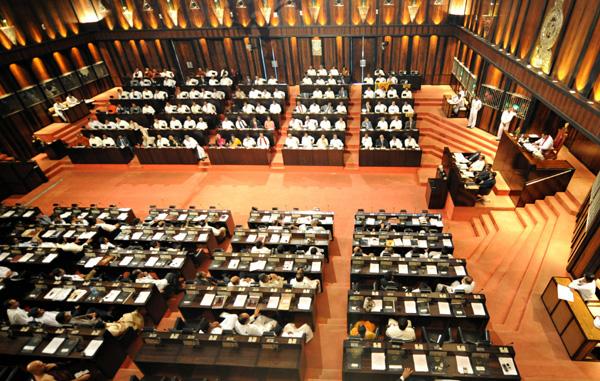

COLOMBO: Government leaders have been saying that the draft constitution will be placed before the Parliament prior to the budget debate that takes place in November. A new constitution which would require a referendum could prove to be the government’s Waterloo if the people reject it.

Last week Chairman of the Public Representations Committee Lal Wijenayake, made an announcement that five of the six sub-committees of Parliament that had been delegated the task of submitting reports on various aspects of the new constitution had completed their work. The Public Representations Committee (PRC), appointed by the Prime Minister with 19 other members, made a special effort in consultations with the general public on the matters connected with the drafting of the new constitution.

Chairman Wijenayake assured those who had made submissions to the PRC that their views would be taken into account in the drafting of the new constitution.

The public consultation process that took place on this occasion, even for a limited period of time, was a new development in Sri Lanka. Both the previous constitutions, the ones drafted in 1972 and 1978, were devised by a few persons drawn from politics and lawyers. They made crucially important decisions without consulting the people and ascertaining their views.

In 1972, the drafters of the constitution decided to subordinate the judiciary to the executive branch of government, which eroded the concept of checks and balances in governance. The people were not consulted regarding this major change that took the country in the direction of authoritarian rule, which is only being reversed today. In 1978 the constitutional drafters decided to vest super powers in the institution of the executive presidency, which further entrenched authoritarian rule, again without obtaining the concurrence of the people.

Unlike in the past, on this occasion, the government conducted public consultations. There have been concerns expressed about the depth and breadth of the consultation process. The time frame of six months was short. The existence of the consultation process was not well known by the general public and therefore public participation in the consultations at all levels was limited.

The exercise was not widely advertised. The members of the PRC had to utilise their contacts and influence to obtain people’s participation. The resources allocated by the government to the consultation process were also limited. But the commitment of those who had been appointed to be members of the PRC ensured that a credible process of consultations took place.

It is worth noting that the 200 plus page report produced by the Public Representations Committee at the end of their consultation is very simply written and clear. It is understandable by those who might not wish to spend too much time studying legal terms. It sets out the major themes of debate on the controversial political issues that have divided the people of the country. It also gives what each of the committee members themselves thought in regard to each issue in order to provide transparency.

Wherever the members of the committee could not make a single recommendation, because of their different points of view, they made multiple recommendations which were often at odds with each other. Their goal was to provide the parliamentarians who are designing the new constitution with a sense of what types of thinking on controversial issues exists at the level of the people.

In this context it was unfortunate that the Joint Opposition should have seized upon some of the recommendations made in the PRC report by some of its members, and claim that they would form part of the new constitution. For instance, on the controversial issues of the foremost place given to Buddhism in the constitution, or the unitary nature of the state, or the merger of the Northern and Eastern province, the PRC gave multiple recommendations, as their members could not agree on a single recommendation with regard to those issues.

The PRC gave the different views that those who came and made submissions before them said. They also provided more than one recommendation when they could not agree to a single recommendation, and also gave the names of those who supported that particular recommendation. The PRC report leaves it to the Parliamentarians, who going to be the final drafters of the constitution, to choose what they wish from the PRC report and recommendations, or choose something entirely different.

Some members of the Joint Opposition have chosen to behave in an unethical manner by misinterpreting the PRC report. They have made the claim that the government proposes to remove the reference to Buddhism from the constitution, do away with the unitary state and merge the Northern and Eastern provinces on the basis of the recommendations in the PRC report. While it is correct that some of the members of the PRC made such recommendations based on the representations they received from the general public, it is not correct to say that the PRC as a whole, or as a majority, made such recommendations. This was not the majority position of the PRC, which adopted the middle position between continuity and change.

The government’s delayed response to the negative campaign of the Joint Opposition based on their misinterpretation of PSC report has given rise to concerns that the government may not take its observations into account at all. So far there has been no sustained or major public education campaign that is based on the report of the PRC. This would be a missed opportunity for public education on the controversial issues of governance on which the people of the country have diverse views, but which will require a mutually acceptable resolution. The PRC report is not only about issues that impact on inter-ethnic relations, but also on other controversies, such as special quotas for women, the rights of sexual minorities, and the rights of disabled persons. The PRC report, which captures the current thinking in society on those issues, ranging from the liberal to the illiberal, would be an excellent educational tool.

There are some special individuals in the polity who could take up this task. Last week former President Chandrika Kumaratunga took up the challenge of educating the people on the value of federal and secular systems of governance. She did this at a workshop organised by the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation which she heads. Flanking her on the speakers’ platform were Minister of National Coexistence Mano Ganesan and parliamentarian Dr Jayampathy Wickremaratne who is entrusted with the drafting of the new constitution.

The former president spoke of the federal system of power sharing as a problem solving instrument in ethnically divided societies, such as semi -federal South Africa and federal Nigeria. She also spoke of the value of secular governance, giving India as a positive example. Those in the audience seemed to go along with what she said, as the question and answer session was lively but not offensive.

At the other extreme, ultra nationalist Joint Opposition leader Wimal Weerawansa is reported to have received a chiding when he met with a leading Buddhist prelate to warn him about the dangers posed to the country by the government’s proposed new constitution. When the Joint Opposition leader had told the Mahanayake of the Malwatte Chapter the Most Ven. Thibbatuwawe Sri Siddhartha Sumangala the that the new Constitution would harm the unitary status of the country, it is reported that the Mahanayake had told the parliamentarian that President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe had assured him that any proposal that encouraged separatism would not be included in the Constitution.

Since the Constitution is to be put to a referendum, the monk had told him and the other National Freedom Front members not to be unnecessarily alarmed about it. The indications are that right thinking people and moral leaders are united in the desire to find a solution, and this is the time to take this message to the people. They know that the political problems that hark back to the days of Independence from British colonial rule will not simply go away, but have to be worked at, and this is the best time to resolve them.

(Jehan Perera is the Executive Director of the National Peace Council of Sri Lanka )